- Almut Boehme tells Jude Rogers how a new exhibition uncovers Scottish music's global influence from the Antipodes to the Americas. This article originally appeared in 'Discover NLS' issue 11.

Traditional folk music has played an important part in the development of Scotland, and today the sounds of singing and playing still resound brightly across both the mainland and islands. But sometimes people fail to realise that Scottish folk music has also exerted a remarkable influence on musical cultures in different lands.

This spring, a new exhibition, 'Scots Music Abroad', sets out to tell the little known stories of Scottish folk music, in particular the ways in which it migrated from its homeland over many centuries. Almut Boehme, Head of Music at the National Library of Scotland, has brought together a fascinating collection of music, diaries, manuscripts and sound recordings from NLS and other library and archive collections, which not only reveal the pride these travellers had in the music that they sang, played and loved, but also their eagerness to share their heritage with others.

Distinct Scottish folk tradition

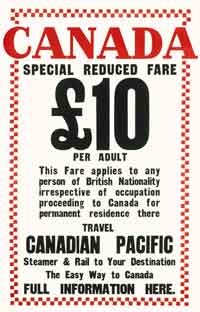

The patterns of migration were not unusual. Many Scots travelled to colonial outposts with the army or navy, while others emigrated when the rise of the British Empire created employment opportunities in countries like Canada and Australia, or when goldrush fever took over the USA. Some were military musicians or the piano-playing wives of middle-class men entertaining visitors in parlours, but others were humble workers who entertained themselves with dances and songs. But when we look at the music that these people sang or played, we find a fascinating distinction between the Scottish folk tradition and those of other countries.

'Scotland is very unusual,' explains Boehme, 'because it's one of the few places in which folk music is performed by amateur and professional musicians of all classes. Folk music had always been valued highly at the Scottish court which led to a unique connection between traditional and classical music. There was no class issue.'

Musicians began to write down traditional music in 'classical' notation which attracted the attention of music publishers in the 17th century. From this time on Scottish traditional music enjoyed both oral and written styles of transmission, quite in contrast to folk music elsewhere. Even now, in the days of modern recording technology, folk music is primarily passed down through the generations orally. This not only shows how keen Scottish people are to document their own heritage in a classical style, but how important folk music has been to all classes and communities.

Available at home and abroad

With the increasing popularity of published editions Scottish traditional music became more readily available at home and abroad.

The Scottish music publisher and collector George Thomson, in particular, was instrumental in helping transport this music abroad, most famously by commissioning foreign composers like Joseph Haydn to write instrumental accompaniments to folk songs.

There were also continental composers working in Scotland like Francesco Geminiani, some of whom embraced Scottish traditional music.

Other composers were not influenced directly by Scottish folk music, but were instead inspired by the country's romantic landscapes and literature, particularly Ossian, Burns and Scott. One of the best examples of such music is Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy's 'Scottish Symphony', completed more than a decade after he visited Scotland. As the romance of the country grew in the mind, it had a pervasive effect on many people.

Stories from an Australian voyage

Scots were also keen to write down their stories about the way music was performed. One of the most fascinating stories of this exhibition is that told in a voyage diary, recounting exuberant tales of impromptu concerts that lightened up journeys.

The diary of Alexander Turner, now held in the National Archives of Scotland, was sent to the Australian High Commission in London from a donor in Australia. It documents the story of a man travelling from Scotland to Queensland, Australia, on a boat teeming with people. His journey began on 20 July, 1883, and almost every day there are stories of singing and dancing on the ship.

When the boat docks on Magnetic Island on 23 October, there is an account of the young men on board playing the fiddle to the people they meet. A strange signature at the end of the diary reveals how these stories may have come home to Scotland.

'The diary, very unusually, is signed by somebody other than the author after the last entry,' says Boehme. 'This man is an Andrew Turner, who we discovered is likely to have been a relation of Alexander. It was practice at the time to make copies of these diaries and send them home - to show, in great detail, what had been happening during these journeys.'

This not only proves how keen the Scots were to stay in touch with their families, but emphasises how music was playing a part in their travels. Another Australian diary, written by a well-to-do woman called Annabella Boswell, tells us how music was prized by those in other social circles.

Like a character in a Jane Austen novel, she wrote about her interests and pastimes. In the journal we can see in the exhibition, she writes about pipers, fiddle music, songs about pilgrims, and her father encouraging her to learn what she calls 'native songs'. She also describes the connections between the locals (whom she refers to as the 'blacks') and the new settlers.

There is also clear evidence of Scottish folk music filtering through to Australian song. The most popular and yet still controversial example, says Boehme, is that of 'Waltzing Matilda', the song often regarded as the unofficial Australian national anthem. Its tune is partly based on a tune called 'Thou Bonnie Woods of Craigilee', which came to Australia through Scottish emigrants.

Cape Breton fiddle music

Scottish folk music was also a strong cultural force in Canada, but this time with fiddle music from the Orkneys and the Highlands becoming particularly popular in Quebec and Nova Scotia. In Canada's Cape Breton Island, musicians developed their own versions of traditional tunes like those found in James Scott Skinner's 'Logie Collection'. Cape Breton fiddle music is widely accepted as one of the major styles of Scottish fiddle music.

Moving south, the story of Scottish music is quite different. While Scottish settlers brought their music to the United States the music had less influence on the new country's canon due to the diversity of immigrants arriving over the centuries. More recent suggestions of a link between African-American gospel music and Gaelic psalm-singing are very interesting, says Boehme, but require further research.

Promoted by Harry Lauder

As we reach the early 20th century, one particular performer is covered extensively in the exhibition. This man is Harry Lauder, an entertainer born in Portobello, Edinburgh, in 1870, whom Winston Churchill generously described as 'Scotland's greatest ever ambassador'.

Dressed in tartan and carrying a twisted hazel walking stick, he performed vaudeville and musical versions of Scottish folk songs, and was so successful in the States that he had an American manager, and was even featured in a 1930 issue of 'Time' magazine. In his later years, the development of recording and communications technologies meant that Scottish folk music could travel all by itself, but Lauder is still remembered fondly by older generations for the way he tirelessly promoted the music of his homeland.

Today, Harry Lauder would see folk music in a very different world. He would have noticed the folk music revival of the 1960s introducing old songs to young audiences at home and abroad, and the wealth of young folk musicians who continue to popularise these traditions today. One would hope that he would be pleased that Scottish folk music still has a global reach, too. In the 21st century, there are thousands of Scottish heritage groups in continents as far-flung as Asia and Africa, as well as Celtic festivals in Canada and Australia that prize Scottish music. There are also regular events in Scotland itself that draw international performers and audiences, keeping the flag flying for the country's rich heritage.

Boehme hopes the exhibition will serve people like Harry Lauder well, and that its resources will deepen our knowledge of the significance and strength of Scottish music. 'The history of Scottish folk music is so vast that this exhibition is just a glimpse into all the stories and sounds of the musical past,' she concludes. 'As our research continues, the story will get even richer.'

Harry Lauder

The Library is rich with resources about the fascinating life of Harry Lauder (1870-1950), the entertainer from Portobello, Edinburgh, who took Scottish music around the world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They tell us how his singing career began in the mill and the pit, how he started singing professionally at 24, and how his touring company rapidly grew in stature both in Britain and beyond.

In 1907, he made his first trip to the USA, a country to which he would return 22 times. The NLS archive includes primitive newsreel footage of one of these trips in 1913, documenting 'His Triumphal Progress from London to Liverpool' as crowds of fans and pipers send him off at the platform and at the quayside.

There are many more delights to be found in the archive. We find Lauder?s personal accounts of tours in America and Europe, sound recordings and films in which he sings his popular songs like 'Nelly Broon', and even a newsreel of him, in his later years, receiving 450 tons of food and clothing from the Scottish settlers in Boston, Massachussetts, sent to help the country recover after the Second World War.

Even after his official retirement from music in 1935, Lauder made wireless broadcasts and entertained wartime troops, showing his commitment to his country's music, and his knowledge of how it could raise spirits in dark times. He died in February 1950 at the age of 79, but his musical legacy lingers.

Scots Music Abroad exhibition

Voyage Diaries

Alexander Turner left Scotland in July 1883 for a new life in Australia. Here are some extracts from his diary, part of the NLS exhibition 'Scots Music Abroad':

'Friday 20 July. We left the Quay at Glasgow?Monday 23 July … we have Dancing on Deck and there is plenty of music on Board? Friday 3 August … the men had a concert to night [sic], it was very good? Tuesday 23 October … We have all landed? one of the young men playing the fiddle to [locals] … they were all dancing.'

More music at the Library

'Hu, Hei, Duncan Gray! Scotland in the Scandinavian musical imagination'

A special lecture-recital exploring Scotland in the Scandinavian musical imagination. 7 April, 7pm, at the National Library of Scotland, George IV Bridge.

'The Austrian Connection: Haydn's Scottish Songs'

Professor Marjorie Rycroft, Professor of Music at Glasgow University outlines the contribution made by the 'inimitable and immortal Haydn' to Thomson's 'Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs'. 21 May, 7pm, at the National Library of Scotland, George IV Bridge.

Booking is essential for both events. Call 0131 623 4675 or email events@nls.uk.

Read the full Discover NLS issue 11 (PDF: 27 pages; 2.3 MB).