- Dr Iain Gordon Brown, Principal Manuscripts Curator at the National Library of Scotland, explores connections that link the creator of Holmes and Watson, Conan Doyle's might-have-been first publisher and military conflicts in Afghanistan.

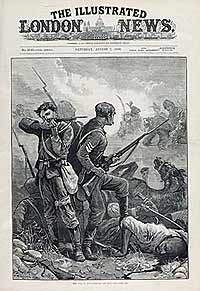

London News', August 1880.

On occasion, a curator in the Manuscripts Division may take the chance to notice connections that present themselves through coincidence or happenstance, and sometimes as the outcome of an intriguing interface between fact and fiction.

Such links may be the result of careful planning through use of catalogues and indices, or of personal knowledge, or they may be prompted by the finding - or more accurate identification - of individual items in the collections not previously linked or overtly connected.

One such moment occurred when I was looking out material for a presentation to a visiting party of United States bibliophiles. With the 150th anniversary of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's birth (1859) in mind, I thought that one of the literary manuscripts I might show should be the short ghost story 'The Haunted Grange of Goresthorpe', written possibly in 1877 or 1878, but which remained unpublished until the year 2000. This Doyle manuscript (MS. 4791), apparently that of his earliest story, antedates the appearance of his first published story in 'Chambers's Journal' in September 1879.

The manuscript of 'The Haunted Grange of Goresthorpe' came to the Library with the archive of William Blackwood and Sons in 1942. Although its existence had long been known, and its likely priority in the Doyle canon appreciated, it was nevertheless recognised as an early work by a still immature talent, and publication was not approved by the keepers of the Doyle flame. It is probable that the historian John Hill Burton, a friend of the Doyle family, had shown the manuscript to John Blackwood, not necessarily in the expectation that his firm would publish it, but as a marker, so to speak, of likely future ability on the part of the young Conan Doyle, a new writer who might one day be worthy of what Blackwood had earlier described as 'the honours of print and pay'. This, rather than Doyle's own speculative submission of his story, seems the most likely explanation of the manuscript's presence among the Blackwood papers.

Britain and Afghanistan

With an eye to pointing out not only the world reach and significance of our collections, but also the relevance of our holdings for today as well as in the time of an individual item's creation, I thought it would be interesting to select for the visiting Americans a couple of things that might illustrate Great Britain's long and unhappy connection with Afghanistan. This was an involvement that led to three full-scale wars in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and to other major campaigns, punitive expeditions and countless more minor skirmishes on the North-West Frontier of India.

From the Minto Papers I chose two volumes of letters from the Governor-General of India, Lord Auckland, to his cousin, the second Earl of Minto. In this correspondence (MSS. 11795-6) Auckland describes his hopes and fears for his policy in Afghanistan, which led ultimately to the disaster of the First Afghan War and the annihilation of the Army of the Indus sent to enforce 'regime change'. Auckland's letters chart his descent from the optimism of 1839 to his despair at the situation prevailing in 1841-1842.

Victorian sentiment had been much affected by the stirring tale of the return of the Scottish army surgeon, Dr William Brydon, who arrived alone at Jalalabad upon a stumbling horse, badly wounded and exhausted, a broken sword dangling from his wrist, as 'the remnant of an army' later immortalised in Lady Butler's famous painting. It was said that Brydon, the sole survivor of the entire British force, had escaped more serious injury because, in a pathetic effort to shield himself somewhat from the intense cold of the Afghan winter, he had stuffed a tattered copy of 'Blackwood's Magazine' into his head-dress, which had warded off some of the tribesmen's knife-blows.

Thus far in my melting-pot, so to speak, of allusion and connection, I already had Conan Doyle and the house of Blackwood, the First Afghan War and the great Edinburgh periodical 'Blackwood's Magazine', in which Conan Doyle, as an Edinburgh man, very much wished to publish some later work. I looked then for something that would illustrate the subsequent disasters and heroism of the Second Afghan War of 1878-1880.

In the index to the manuscript collections I found an item that looked hopeful, to me at least, if not to the shades of poor British, Indian and Gurkha soldiers whom I sensed peering over my shoulder as I read the index slips. They had perished in a campaign that had the single merit of propelling to prominence the future Field Marshal Earl Roberts, VC, archetypal Victorian hero, and enshrining in legend his epic march from Kabul to Kandahar. 'Afghan War, 1878-80, letters concerning battle of Mazra (1880), MS. 2544, ff. 130-9' said the index. The name of this engagement was new to me: I had never heard of it. I was dubious. I went to the strong-room shelf. My scepticism was proved correct. The letters clearly described the Battle of Maiwand and its aftermath.

Battle of Maiwand

Maiwand was etched on the British military memory. Like Isandlwana in the Zulu War only the previous year it was a bloody defeat. A strengthened brigade under Brigadier General GRS Burrows had crossed the Helmand River (Helmand! - a name we today hear daily as our own forces engage the Taliban on this same ground) and had found itself outnumbered seven-to-one by the combined forces of Ayub Khan, both regular Afghan army troops and irregular hordes of ghazi warriors. The brigade was forced to fight on disadvantageous terrain and once routed, had to retreat to Kandahar in disorder.

Dr Watson, Conan Doyle's fictional creation, had served at Maiwand as Medical Officer of the 66th Foot, the Berkshire Regiment, to which he had been seconded from the Northumberland Fusiliers. At Maiwand he had received the wounds which troubled him in his postwar life in Baker Street. But at least he had a postwar life. A thousand other men were not so fortunate, for Burrows' force was badly mauled and casualties were very high. Among those who lost their lives was Major George F Blackwood, commanding E Battery, B Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery. He was younger brother to 'Willie' Blackwood, who in 1879 had become editor of 'Blackwood's Magazine'. Another piece of my self-made jigsaw was falling into place.

The Maiwand letters in MS. 2544 were written by an officer of the 66th, Major John T Ready. The recipient was an Army Medical Service (as it then was) officer, John Stewart Lithgow, an Edinburgh graduate and subsequently a much-decorated Major-General, whose papers came to the Library in 1938. (Doyle certainly, and possibly the fictional Dr Watson too, were also Edinburgh medical students.)

Ready's account brings us close to the horror of that dreadful day, from which he and all too few others escaped in the rout due to luck and their role in the action. His commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel James Galbraith, nine other officers and nearly 300 men of his battalion fell and 50 more were wounded, Galbraith and some others (the badly wounded Blackwood among them, unable to ride with his battery) having made three desperate rallies in an attempt to save the colours of the 66th, those potent symbols of regimental identity and of Queen and country still being carried in action as late as 1880.

Both colours were lost in the wreck of the shattered battalion, of which the last remaining 11 officers and men made a final stand, all to be killed. The two Indian infantry battalions of Burrows' brigade suffered even greater losses, with the 1st Bombay Native Infantry (Bombay Grenadiers) faring particularly badly with some 370 dead. (Jacob's Rifles, 30th Bombay Infantry, lost nearly 250 dead). The two Indian cavalry regiments also present proved less resolute than might have been expected.

Royal Horse Artillery

The importance of traditional research in primary and serious secondary sources such as official military histories (that for the Second Afghan War having been published by the firm of John Murray) cannot be over-stressed today, when so much of what passes for 'research' is done from the internet. If one looks at some electronic sources, one would believe that when mention is made of 'the [Bombay] Grenadiers' it was the Grenadier Guards that is being referred to. That most distinguished regiment was neither present at Maiwand, nor even engaged in the war; yet one article on the internet maligns them for cowardice in the battle.

When I last looked at it, the Wikipedia article on Maiwand used a celebrated painting by Richard Caton Woodville showing the Royal Horse Artillery saving their guns - a sacred duty for Gunners - under heavy fire when out of ammunition and with the enemy almost on their position. This gallant episode was captioned as the 'Royal Horse Artillery fleeing before Afghan attack', which is not quite the same thing! Maiwand lives in memory as a shocking defeat for British imperial arms, the disgrace being relieved only by the Boy's Own heroism of the Berkshires' last stand and the RHA's daring extraction of their guns.

Major Ready's first note to Lithgow, written from the relative safety of a besieged Kandahar, asked him to let his wife know in Reuters cipher that he was all right. The message ended in a pencilled scrawl, as he listed his brother officers as either killed, wounded or missing as he knew the facts to be. Having fought all day in a 'broiling sun' and with no food, he had been on the night march for 45 miles, 25 of them without water, and was 'still half dead with fatigue & thirst.' Otherwise he was unscathed apart from a twisted ankle. During the action he had personally bandaged the serious wound in Blackwood's thigh.

Among the wounded, Ready mentioned 'Dr Preston'. This was his battalion's Medical Officer, Surgeon Major AF Preston. It is the firm belief of the modern-day regiment, which is the descendant of the old 66th Foot (that unit having passed through many amalgamations and name-changes to form today's 1st Battalion, The Rifles), that Preston was the model for Sherlock Holmes' Dr Watson, who suffered similar injuries. And where has that modern Rifles battalion been serving? Helmand Province, Afghanistan.

So, many notions appear to come full-circle when one begins to browse and muse among the manuscript collections.

Read on with NLS

- 'The Second Afghan War 1878-80. Abridged Official Account' (London: John Murray, 1908) [National Library of Scotland reference: S. 15.c]

- 'North-West Frontier. People and Events 1839-1947', Arthur Swinson (London: Hutchinson, 1967) [NF. 1240.e.8]

- 'Afghan Wars and the North-West Frontier 1839-1947', Michael Barthorp (London: Cassell, 2002) [HP3.203.1462]

- 'My God - Maiwand!', Leigh Maxwell, (London: Leo Cooper, 1979) [H3.79.1803]

Dr Watson and Maiwand

Sherlock Holmes was first introduced to the world (and through the medium of the fictional Dr John Watson's putative 'Reminiscences') in 'Beeton's Christmas Annual' for 1887. The story shared the volume with two pieces by other authors, both now wholly forgotten. Arthur Conan Doyle reissued his story, 'A Study in Scarlet', as an independent book the next year with the same publisher as that of the annual, Ward, Lock and Co.

Dr Watson opens the story by telling the reader about his service as an army doctor in Afghanistan. He explains how he had been seriously wounded in the shoulder at Maiwand and recounts that due to the courage of his orderly who had found transport for him, he had been lucky to survive the retreat to Kandahar. Watson's experiences mirror those of the real-life Medical Officer who was the model for his character. Dr Preston left a graphic account of his remarkable survival after Maiwand, when he too owed his life to the bravery of those who stayed to help him and bring him out of danger.

The opening page of 'A Study in Scarlet' in its first edition carries Watson's story of Maiwand and its aftermath. A passage on page 13 shows Sherlock Holmes explaining to Watson how he had instinctively known that a man, previously a stranger to him, had returned recently from active service in Afghanistan.

Read the full Discover NLS issue 13 (PDF: 27 pages; 2.4 MB).