Reading Time: 12 minutes

Long readWritten by Ali Leetham

19th-century Scottish legal systems targeted queer people. Writer and archivist Ali Leetham reveals the intersection of sexuality, class, and state power through archival research.

At the Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive, we recently put together the 'Desire Paths' exhibition, which mapped Edinburgh's queer history over the last 200 years. The focus of my research for it was the criminalisation of the queer community.

Queer people writing about their own experiences were rare before the 20th century, and those in power often preferred to cover up queer criminal cases rather than have to discuss queerness publicly. There are many books and resources about how queer people were treated by the state in the 20th century. While 19th-century sources exist, they are harder to come by and are often erased from canon.

Ordinary queer people victimised by the state in the 19th century are therefore at risk of being forgotten. This was something I wanted to rectify in Desire Paths, so I decided to investigate.

The 'Desire Paths' exhibition at Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive in February 2025.

The law and precognitions

To begin my investigation, I visited the National Records of Scotland (NRS). As a depository of records including court documents dating back to the 12th century, it's a good place to start when researching criminalisation.

To find relevant records, it's important to be clued up on legal lingo and the language of the time. Words like 'gay' and 'queer' hadn't acquired their modern meanings in the 19th century. Although the word 'homosexuality' was used in medical literature by the late 19th century, it wasn't used in legal contexts.

When men were arrested for having sex with each other, the crime they were often charged with was called 'sodomy'. But despite being a legal term, 'sodomy' wasn't very precise. Some commentators unhelpfully described it as a crime too abominable to be named by Christians. The term could be used to describe a whole range of sexual acts that weren't procreative. So, as well as sex between men, sodomy charges could be brought for some heterosexual sex acts, and even bestiality.

To her credit, the NRS archivist didn't bat an eyelid when I said I was looking for sodomy, and I soon had a handful of documents in front of me. Written on yellowing sheets of foolscap bound together by a ribbon, my first challenge was deciphering the documents. As typewriters hadn't yet been invented, they were handwritten.

The documents I was studying are known as 'precognitions'. Unique to Scots law, this term refers to written statements from witnesses. My first document, from 1845, contained precognitions from a labourer called William Simpson and a baker called Ralph Dodds. They'd been caught having sex in a common stair in Campbell Close on Edinburgh's Cowgate.

This showed that immediately after their arrest, the surgeon of police subjected them to an intrusive medical examination, which seemed to be a standard method of gathering evidence in sodomy cases. The medical certificate claimed the doctor observed redness that "was greater than is generally observed in natural connection" [heterosexual sex].

With such scientific evidence as this on its side, the state took the case to trial a month later. Simpson and Dodds were tried at the High Court in Edinburgh, which is meant for the most serious criminal cases, such as murder. They were convicted of attempted sodomy and sentenced to transportation for 10 years.

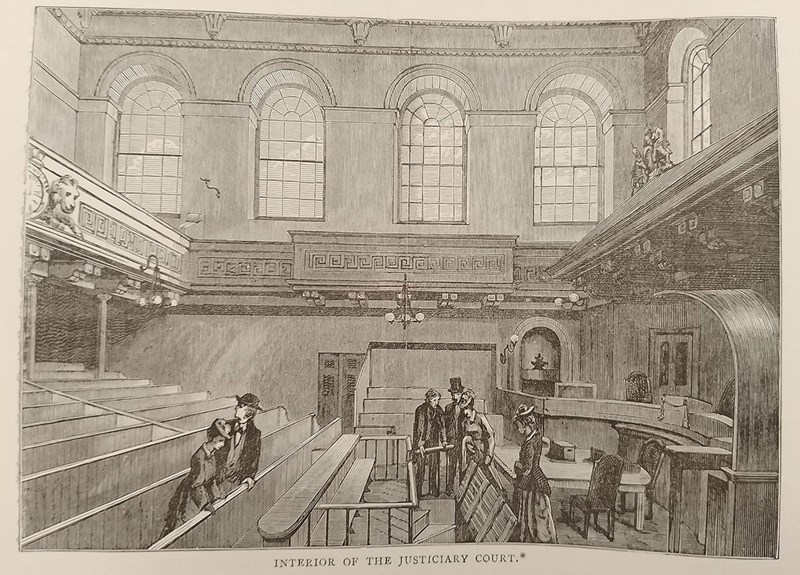

To get a feel for what Edinburgh was like at that time, I turned to the National Library of Scotland's collections. 'Cassell's Old and New Edinburgh' was a periodical printed in the 1880s, full of history, anecdotes and sketches of Edinburgh's landmarks. It was later republished as a book, which is available in the General Reading Room at the National Library. But I went up to the Special Collections Reading Room to flick through the originals.

The 19th-century illustrations offer a unique glimpse of Edinburgh as it looked to Simpson and Dodds, such as this interior of the High Court, one of the last places in Edinburgh they would have seen before being sent to Australia.

The High Court of the Justiciary, where Simpson and Dodds were tried. 'Cassell's Old and New Edinburgh' gives us a glimpse of how it looked at the time. James Grant, 1885-1887. (ABS.8.99.2)

Transportation

Sodomy was considered a serious crime in 19th-century Scotland and could legally be punished with death until 1887. However, no executions for sodomy actually took place in Scotland in the 19th century, and queer men were instead sentenced to imprisonment or transportation.

Following the Transportation, etc. Act 1785, Scotland transported convicts and political prisoners to penal colonies in Australia until 1868. Prisoners were free to leave after serving their term. But since they had to make their own way back, most spent the rest of their lives in Australia.

A survey by Bruce Baskerville found that while the majority of people transported were from London and other urban centres, most of those transported for sodomy specifically were from rural areas or the military. What's more, men indicted for sodomy in Britain were mostly gentlemen and skilled artisans, as well as professionals and clergymen. However, the ones who were actually sentenced to transportation were overwhelmingly unskilled labourers and soldiers. In fact, none of the gentlemen, professionals or clergy faced transportation for their sodomy indictments, suggesting a clear class bias in how this punishment was meted out.

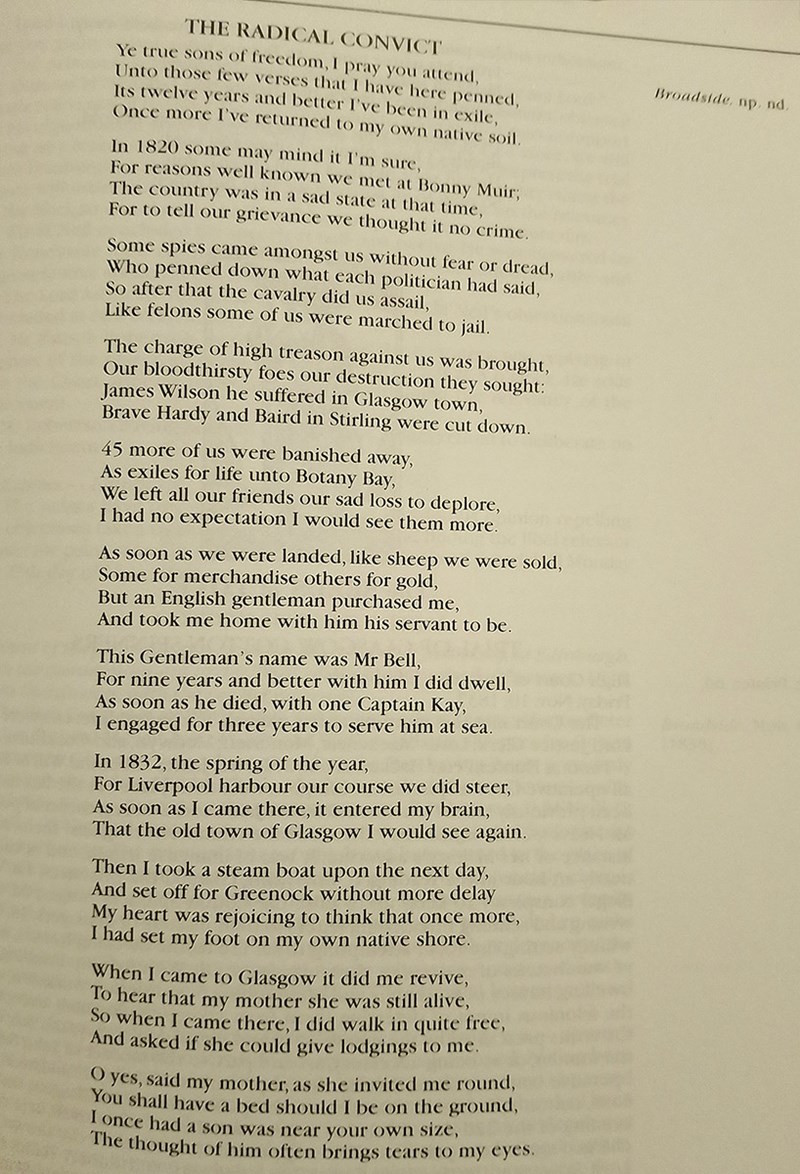

Written by those in authority, the legal documents only gave me a very limited view of the experience of transportees. That's why I requested to view 'Farewell to Judges & Juries' in the General Reading Room at the National Library. The oral tradition and popular written media like these ballads preserve the stories of ordinary people. Many were written in the 18th and 19th centuries from the perspective of those sentenced to transportation.

This broadside ballad recounts the experience of one of the Glasgow radicals who took part in the 1820 insurrection at Bonnymuir and was transported to Botany Bay as punishment. From 'Farewell to Judges and Juries', Hugh Anderson, 2000. (HP3.203.0748)

Transportees would be put to work to meet the colonies' labour needs. They wouldn't spend their full sentence in prison, as the colonies had a graded parole system. After serving some of their time, prisoners could receive a ticket of leave, which allowed them certain freedoms, such as seeking employment. They could then progress to a conditional pardon and conditional freedom.

Despite seeming to have more freedom than prisoners back in Scotland, the transportees could face harsh punishments for breaching the colonies' strict rules. William Rind, a mixed-race Chelsea Pensioner from Stirling who was transported for sodomy in 1846, was sentenced to 14 days' hard labour in chains just for having a bag and a towel in his possession. Meanwhile, Henry Johnson, a shipwright and sailor from Ayr convicted of sodomy in 1842, was cited for multiple punishments in Australia, from 5 days of solitary confinement for idleness to 2 months' hard labour in chains for owning tobacco.

Many people argued against transportation on the grounds that it was inhumane or ineffective. Certainly, it may not have had the intended effect as a punishment for sodomy. Several contemporary authorities claimed that queer sex was widespread in Australian convict populations, including among the female convicts.

A case study: William Aitken and James White

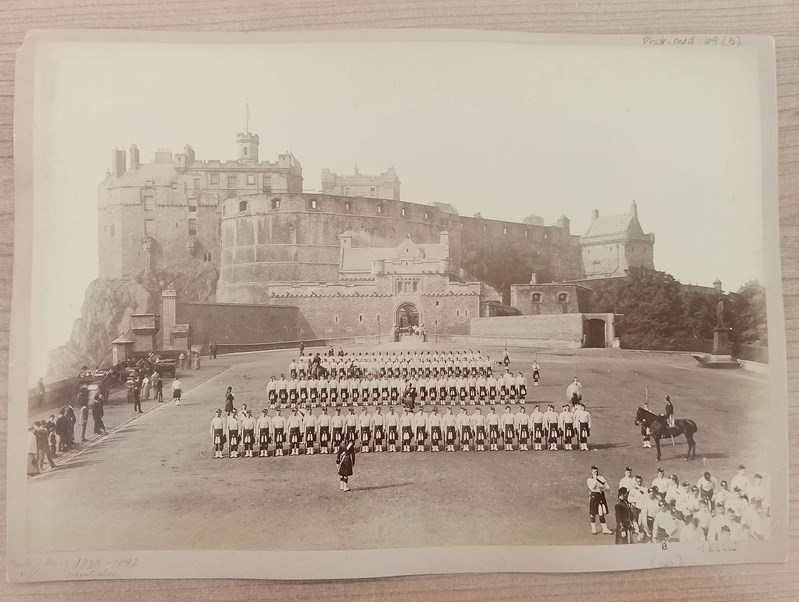

For the 'Desire Paths' exhibition, I decided to focus on the experiences of two men in particular. William Aitken and James White were both privates in the 79th Regiment of Foot, also known as the Cameron Highlanders, who were stationed at Edinburgh Castle in 1852.

I found lots of material on the Cameron Highlanders at the National Library, from photos to histories to records of all the officers. My favourite was this photo from 1888 of Aitken and White's regiment on parade in front of the castle. It was taken three decades after Aitken and White left, but it gives a picture of how they looked in their uniform, and how similar the esplanade looks today.

Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders on Parade, 1888. (phot.med.64(3)). This photo is available to view in the Special Collections Reading Room of the National Library of Scotland.

William Aitken, originally a tailor from Cupar, went to the Crown Tavern on 28 August 1852. After an evening spent drinking with some women from Dundee, he returned to the castle around 9 pm. Meanwhile, Edinburgh local James White, who was a trained carpenter, was on something of a pub crawl. Although the details were a bit hazy, MacRaes public house on the corner of Nicolson Square was the last place he remembered drinking.

On returning to the Old Barracks in rather a merry state, White stayed up late chatting with Aitken, whose bed was a few inches away in their shared dorm. After the candles were extinguished, they both climbed into bed together. Unfortunately, another private in the dorm overheard the beds shaking and alerted the corporal next door, who fetched the sergeant.

The two men were quickly taken into custody and watched over until morning. Although there was talk of court martials, the general ultimately decided to hand them over to the civil authorities.

Aitken and White were transferred to Calton Jail to await trial. Built on the site now occupied by St Andrews House, the jail was so large and foreboding that some 19th-century tourists mistook it for Edinburgh Castle.

This map shows how Edinburgh looked in the 19th century and can be viewed in the Maps Reading Room in Edinburgh or online through Georeferenced Maps. OS Six-Inch (1840s-1880s).

The two soldiers would have been put to work while they were incarcerated at Calton Jail, likely through 'hard labour'. This was also where they were intrusively examined by Dr Rob Paterson. Although the doctor admitted he found no evidence of sodomy, he felt the need to add that he also found "no deformity or abnormal development that would be a hindrance to committing such a crime." Incriminating evidence indeed.

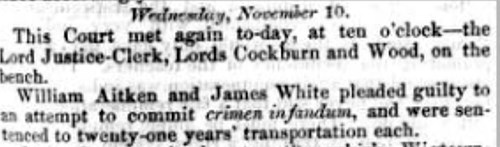

Like Simpson and Dodds a few years earlier, the soldiers were tried at the High Court. Another great resource for learning about historical court cases is the British Newspaper Archive, which I was able to view on the computers at the National Library. I found this piece in the Edinburgh Evening Courant, which shows that on the 10th of November, Aitken and White received an even harsher sentence of transportation for a term of 21 years.

Crimen infandum means 'the unspeakable crime' and is used to mean sodomy in this newspaper article. From the Edinburgh Evening Courant, 11 November 1852.

Transportation registers show that the two men were taken to Portland to wait for a ship. On the 21st April 1855, they set sail on the convict ship Adelaide with 257 other prisoners. The voyage took 90 days, and one person died on the way.

As Australian convict records often included appearances, I got a glimpse of how the men looked. William Aitken was 5'9" with dark brown hair and eyes, a long face and a small scar on his right eyebrow. James White was three inches shorter with light brown hair, grey eyes, a round face and tattoos of anchors and his initials.

On 18th July 1855, the Adelaide docked at the newly-founded Fremantle colony (modern-day Perth) on the Walyalup land of the Whadjuk Noongar people. Aitken and White likely didn't spend very long in Fremantle prison (recently built by convict labour) as prisoners were soon put to work building much-needed infrastructure for the colony. As Perth gaol was built by convicts between 1854 and 1856, the two men may have helped build it.

In 1857, both men received their tickets of leave. White received a conditional pardon in 1862, and Aitken in 1864. This was the last piece of evidence I could find of William Aitken's life. James White, on the other hand, was working as a carpenter in Roebourne (Yirramagardu), on Ngarluma country, when he died of a stroke after a heavy drinking session in 1868. He was buried in a coffin that he made himself.

The contemporary gay subculture

By the time of Aitken and White's transportation, a rich gay subculture had long been established in London, and likely in other cities, too. 'Mollies' was the term mostly used for gay men in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The mollies were working class and would socialise in certain taverns known as molly houses. Here, they could get 'married', which might involve spending the night together in a room with a double bed. They may also have dragged up for masquerades and hosted performances of mock births.

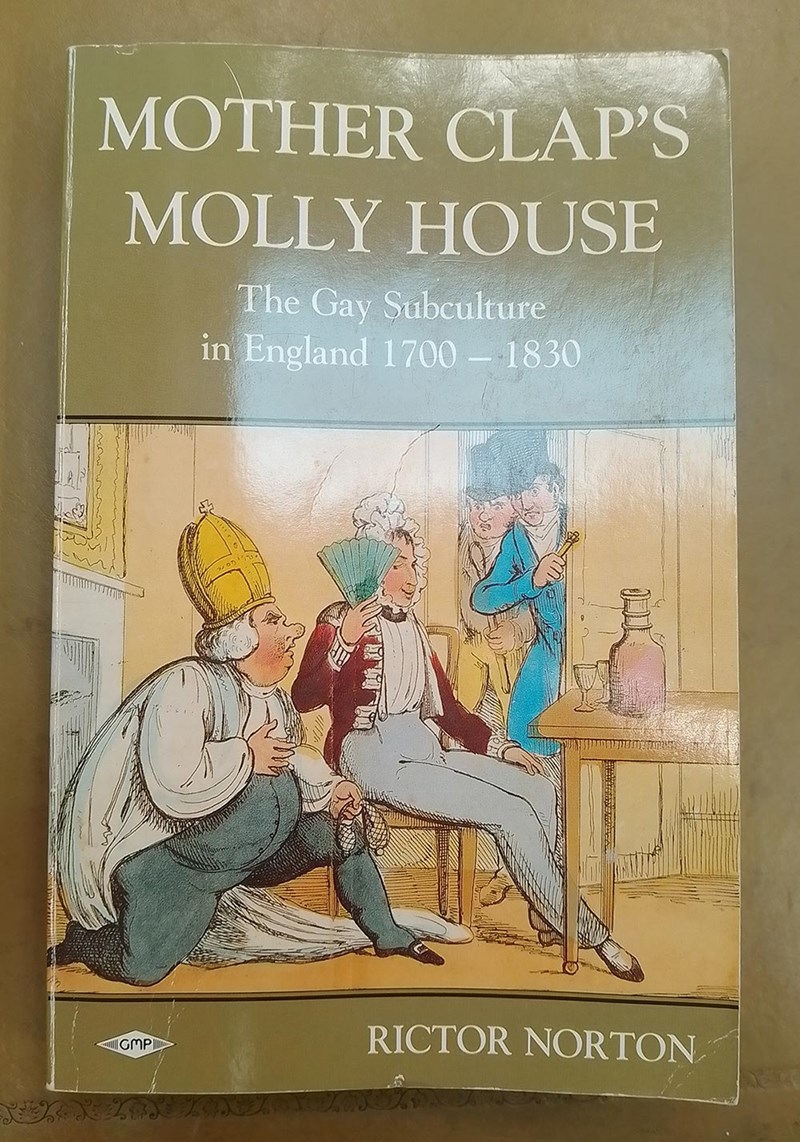

The molly subculture lasted until the mid-19th century, and the most enlightening book I found on it in the National Library collections was 'Mother Clap's Molly House' by Rictor Norton. It provided me with a wealth of information on the historical activities and experiences of queer men, based on legal documents, newspapers, popular media and more. (Norton maintains source guides online too!)

'Mother Clap's Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England 1700 - 1830', Rictor Norton, 1992. (HP2.93.4839)

For example, mollies had their own vocabulary of slang language. It was a descendant of thieves' cant and an ancestor of Polari, the gay lexicon made famous by 'Round the Horne' in the 1960s. The mollies' 'female dialect' involved using 'maiden names' for each other, such as Dip-Candle Mary and Princess Seraphina.

Other than molly houses, queer men could find each other at cruising spots, which they referred to as 'markets'. Edinburgh's Calton Hill has long had a reputation for cruising, and it may well have served as a place to 'pick up trade' (find a sexual partner) in the 19th century and even earlier.

During the 19th century, mollies began to be superseded by other gay subcultures, such as the Margeries. 'The Yokel's Preceptor', a booklet published around the time of Aitken and White's transportation as a guide to London for the inexperienced, included a warning about Margeries:

"They generally congregate around the picture shops, and are to be known by their effeminate air, their fashionable dress, &c. When they see what they imagine to be a chance, they place their fingers in a peculiar manner underneath the tails of their coats, and wag them about – their method of giving the office."

Bathhouses have historically been another site for queer assignations. Many were built across Scotland in the 1850s following the 1846 Act to Encourage the Establishment of Public Baths and Wash-houses.

Edinburgh police discovered in the 1930s that the vast majority of visitors to the Russian baths on Glenogle Road and Infirmary Street (now Dovecot Studios) were there for 'homosexual practices'. As these sites were so well-established by then, it's possible gay cruising had been happening there since the baths' early days in the late Victorian period.

Reflections

The cases I examined demonstrated the huge impact that the law can have on the lives of queer people. Understanding this impact is important not just in studying history but in appreciating the relationship between legal decisions and queer lives today.

Transportation was a dark chapter in Scotland's legal and LGBTQ history, but one worth remembering. Although all the legal documents, newspaper articles and other pieces of evidence I studied were in publicly available archives, they weren't necessarily easy to find or well-examined.

Queer lives are often left out of the mainstream narrative of history, and I hope the work we did on the 'Desire Paths' exhibition went some way to addressing this gap. I'm sure we've barely scratched the surface, though. Now, it's up to historians, archivists and enthusiasts to seek out and share the many other queer stories held within the collections at the National Library of Scotland and elsewhere for the benefit of us all.

The word "queer" is used in this article as a modern umbrella term to describe a range of non-heteronormative sexualities and gender identities. It’s important to acknowledge that it may not reflect how individuals described here identified at the time, but it offers a respectful and inclusive way to discuss their experiences today.

About the author

Ali Leetham (she/her) is a writer and volunteer archivist at the Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive. She co-curated their 2025 exhibition 'Desire Paths: Reading Queer Edinburgh'. Ali is working on oral history projects for Lavender Menace and the Regional Ethnology of Scotland Project. She loves researching the intersections between history, literature, LGBTQ+ culture and food to uncover the stories hidden in the margins.

About Lavender Menace

Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive is a Community Interest Company established to promote and benefit the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, non-binary, queer, intersex, asexual (LGBTQIA+) community and their allies. Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive works to create and maintain a free and welcoming community archive space for reading, research, and socialising.