Aldo Manuzio (Aldus, as he was usually known, from the Latin form of his name) was the first and most celebrated of the scholar-printers of the Renaissance, a role defined by H George Fletcher as follows:

'… a professional who printed his own works or had some hand in the editorial content of the books that issued from his press, either as editor, commentator, or translator; moreover, he was thoroughly trained in the classical languages and printed classical and Biblical texts from manuscripts that he himself edited, emended, or translated into Latin from Greek, occasionally writing commentaries on them; finally, he is someone whose reputation in typography is as great today as is his renown in scholarship.' (Fletcher, 'New Aldine Studies', p.19)

Many of the early printers, like the goldsmith Johann Gutenberg, had a background in the crafts necessary for the technological aspects of printing. Of Aldus' predecessors in Venice, for instance, Nicholas Jenson was a metalworker, and Erhard Ratdolt came from a family of woodcarvers. Aldus, however, was first and foremost a scholar. After a successful career studying and teaching in Italy, he turned to an entirely new occupation as a publisher at the age of 40. He stated many times that his goal was to make available in print the classic texts of the ancient world which so excited Renaissance humanists.

Aldus' printing career began in Venice in 1495. The city had already become the centre of the European book trade: with its close connections to nearby universities, its trade networks, and its cosmopolitan community of scholars, including many Greeks exiled after the fall of Constantinople, it was the ideal place for what he wanted to achieve.

Three signficant Aldus books

Three books are featured here to represent the key aspects of Aldus' career:

- His mission to publish scholarly editions of the Greek classics

- His relationship with contemporary humanists such as Pietro Bembo

- His seminal series of 'pocket editions' of canonical texts.

It is no coincidence that each item also represents an important moment in the history of the book. Aldus' edition of Aristotle epitomises the role of printing in re-introducing original Greek texts to the western world after centuries of unavailability. 'De Aetna' marks the first appearance of the font named 'Bembo' after the author, a Roman type still in use today. Small formats like that of the Aldine 'Petrarch' liberated books from the study and brought them into everyday life.

It was his enthusiasm for spreading knowledge of Greek in particular that drove Aldus to print, and his edition of the complete works of Aristotle is a typical — perhaps the supreme — example of the kind of scholarly folio volumes he produced in the early years of his career. The 'editio princeps' (first printed edition) of Aristotle's works in the original Greek was one of the earliest he undertook. The first volume, the 'Organon', or Aristotle's six treatises on logic, appeared in 1495, with four subsequent volumes containing the rest of Aristotle's works published by 1498.

Shown above is the first leaf of the 'Categories', the first Aristotelian text in the 'Organon'. Few of Aldus' publications would contain the kinds of decorated borders and capitals used here. Aldus' Greek fonts were as widely imitated as his Roman ones and were also based on contemporary scholarly calligraphy. However they differ from the modern standard, particularly in their use of ligatures to join letters and accents together, so that his Greek books are less readable today.

In all, Aldus produced some 30 'editiones principes' of major Greek authors. Ever the teacher, he also published Greek grammars and other books to help those who wanted to learn the language.

Pietro Bembo: 'De Aetna'

Pietro Bembo, a humanist from a noble Venetian family, was one of Aldus' most important collaborators, supplying him with the manuscript for the 'Erotemata', a treatise on Greek grammar by Constantine Lascaris which was probably the first book Aldus printed. 'De Aetna' ('On Etna') was inspired by the trip to Sicily on which Bembo collected the 'Erotemata' manuscript. This work, a Latin dialogue between Pietro and his father, also a noted scholar, about their trip to Mount Etna, is in itself a fairly insignificant example of humanist imitation of the classical style. Its importance for modern readers lies in the design of the book: it marks the first appearance of the Roman font that would be called 'Bembo' and is still in use today, revived by the great typographer Stanley Morison as Monotype Bembo.

Aldus was not the first to use Roman type, but it was Aldine Roman that became most influential. The type was cut by Francesco Griffo, who designed all of Aldus' major fonts, including the Greek and italic shown above and below. Griffo's role in the design of Aldus' books was as important as that of Aldus himself. Perhaps he felt underestimated — he would break with Aldus in 1503, and cut similar type for a rival printer. Griffo disappears from history in 1516 when he was accused of murdering his son-in-law with an iron bar — perhaps one of the very punches he used for cutting type?

In its perfect simplicity, the design of Aldus and Griffo provided a model for how printed books should look that has lasted for 500 years. The image shown above highlights their use of new forms of punctuation that would become standard: this is the first appearance in print of the semi-colon.

The Aldine 'Petrarch'

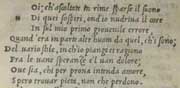

In 1501 Aldus began to publish a series of books in octavo format that would become the quintessential Aldine editions. He called them 'libelli portatiles' ('portable little books'), and they consisted of the works of noted authors stripped of the commentaries that traditionally surrounded them, printed in an italic font that imitated the finest humanist calligraphy: classic texts made new for his contemporary readers.

Whereas scholarly tomes such as Aldus' own Aristotle edition were large volumes designed for use in the study, his 'Petrarch' — an 'enchiridion' (handbook) — could be taken anywhere. The obvious point of comparison for modern readers is with paperback series of 'classics', although Aldus' books were not noticeably cheap and were aimed at the intellectual rather than the man in the street. 'Portable' books had been printed before, but always for devotional purposes: Aldus gave the same convenience to a readership of Renaissance humanists, who were as likely to be travelling around Europe or passing the time at court as they were to be safely ensconced in libraries.

As a vernacular text, this edition of Petrarch's poetry was untypical of Aldus' output. But Petrarch, like Dante (whose 'Divine Comedy' would be issued in the octavo series in 1502) was central to the developing Italian literary canon. This edition was a controversial one: Pietro Bembo, again working with Aldus, produced a text from a manuscript 'in the Poet's own hand', which not only removed the usual commentaries but applied humanist methods of textual editing to produce some striking new readings which had to be justified in a postscript.

The influence of the Aldine Press affected every part of the book trade. Aldus was a model for scholar-printers across Europe such as Josse Badius, the Estienne family, and Christopher Plantin, and later for the university presses. Typographers and designers have constantly returned to Aldus' books, imitating and being inspired by his minimalist design. But perhaps the real heirs of Aldus Manutius are all those who share his primary motivation — to make accessible the great works of the past to a contemporary audience.

The dolphin and anchor

No discussion of Aldus would be complete without a mention of his famous device, the dolphin and anchor. Originating from a Roman medal given to him by Pietro Bembo, the image was used by Aldus to symbolise his publishing achievement of 'producing much, but slowly'. The device would become the stamp of an Aldine book, and Aldus yet again set a fashion other printers would follow in using it to identify his publications. First used in 1501, the device does not occur in the three books above (the image shown here is from his 1502 editio princeps of Sophocles, one of its earliest appearances)

Aldine Press books in the National Library of Scotland

The Library holds over 40 editions of books printed by Aldus before his death in 1515, with more than one copy of some. It also holds many Aldine Press books printed after Aldus' death, when the firm was carried on first by his business partner Andrea de Torresani and later by his son Paolo Manuzio, and examples of the 'pirate' or 'counterfeit' editions produced by rival printers.

The publication 'Short-title catalogue of Foreign Books printed up to 1600 … Now in the National Library of Scotland' (shelved in the Special Collections Reading Room) contains details of all Aldine items acquired before 1970. Later acquisitions, including many Aldine books in the Newhailes collection, are on the online catalogue, as are many of the entries in the Short-Title Catalogue (with more being added as retroconversion takes place). The easiest way to find books printed by Aldus in the online catalogue is to search using imprint details, in their original languages, as keywords in Advanced Search.

Details of featured books

- Aristotle: ['Works', volume 1]. Colophon dated 1st November 1495 (shelfmark: Inc.190. Other volumes are at: Inc.195-198* and Inc.199.5, including duplicates)

- Pietro Bembo: 'De Aetna'. Colophon dated February 1495/6 (Inc.192)

- Francesco Petrarca: 'Le cose volgari di Messer Francesco Petrarcha'. Colophon dated July 1501 (Nha.T189)

- Sophocles: 'Sophoclis tragaediae septem cum commentariis'. Colophon dated August 1502 (K.37.g)

Further reading

- Fletcher, Harry George: 'New Aldine Studies: Documentary essays on the life and work of Aldus Manutius'. San Francisco: Bernard M Rosenthal, 1988 (Shelfmark: H4.90.11)

- Lowry, Martin: 'The world of Aldus Manutius'. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1979 (H4.79.720)

- Renouard, Antoine-Augustin: 'Annales de l'imprimerie des Alde'. Paris: A A Renouard, 1825 (2nd. ed.) (AB.3.86.5)

- Richardson, Brian: 'Printing, writers and readers in Renaissance Italy'. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999 (H3.200.1200)

The Library also holds catalogues of exhibitions of Aldine material, many reflecting the 500th anniversary of Aldus' first printed book in 1995.

Websites

- Aldus' masterpiece, the 'Hypnerotomachia Poliphili' (1499), is celebrated by the Special Collections department of Glasgow University Library at http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/month/feb2004.html

- The University of Pennsylvania Library's online exhibition 'Petrarch at 700' sets the Aldine edition of Petrarch's poems in the context of other early printed editions: http://www.library.upenn.edu/exhibits/rbm/petrarch/petrarch_print.html

- Online Aldus exhibition at the Harold B Lee Library of Brigham Young University, USA — a print catalogue of this exhibition was published as 'In Aedibus Aldi' (Provo, Utah: Friends of the Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University, 1995, shelfmark HP4.96.55): http://exhibits.lib.byu.edu/aldine/