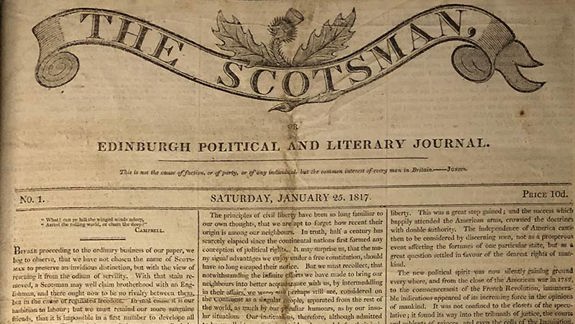

Scottish Broadsides: Three centuries of news and views

Introduction

What is a broadside?

Broadsides were single sheets of cheap paper, printed on one side only. They were designed to be read unfolded, posted up in public places and then thrown away. At first, broadsides shared royal proclamations, acts, and official notices. Later they encouraged political agitation and influenced popular culture.

Sold by pedlars or pinned up on walls in ale-houses, most broadsides cost a penny (around 16 pence in today’s money) or halfpenny. Unlike more expensive newspapers, which were taxed until 1855, broadsides were priced low enough to be within the means of most working people.

Though intended to be temporary, disposable publications, many broadsides survived for hundreds of years. The National Library of Scotland holds thousands of broadsides, which offer valuable insights into the societies they were published in. They cover topics as diverse as crime, politics, fashion and mermaids.

Ballads

At a time when many people couldn't read, street balladry was a popular form of entertainment, which also shared the latest news with ordinary people. Early ballads told dramatic or humorous stories, which were passed down through word of mouth. Many survive today only because they were printed on broadsides. The term 'ballad' was later applied more broadly to any kind of topical or popular verse.

Most broadside ballads were sung in the street by hawkers who also sold copies of the printed version. They became popular in Britain during the Reformation and told stories of all kinds, from romance and tales of exile to politics and sport.

"A bonny Lad of High Renown,

who Liv'd in Aberdeens fair Town,

Courted Young Jenny blyth and gay;

but she Swore he's stoln her Heart away."

Verse from 'A Bonny Lad of High Renown', 1701

Scottish writers like Robert Burns, Allan Ramsay and Robert Tannahill penned words for ballads, but ballad composers were generally unknown. Tunes tended to be established favourites and musical notation was rarely printed alongside the words.

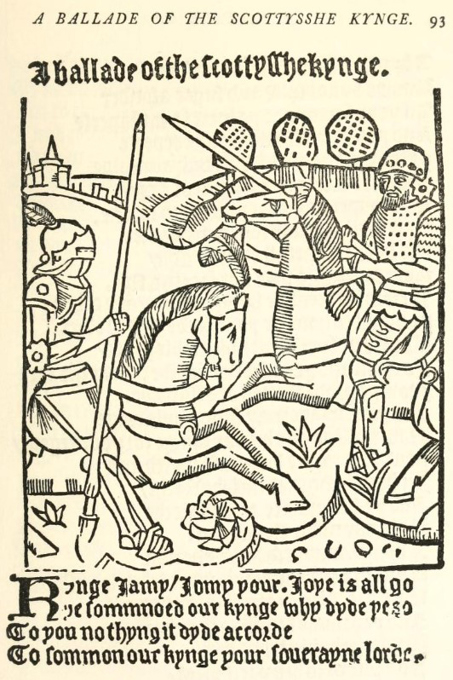

Among the earliest ballads printed was 'The ballade of the Scottysshe Kynge', written by John Skelton about the battle of Flodden Field in 1513.

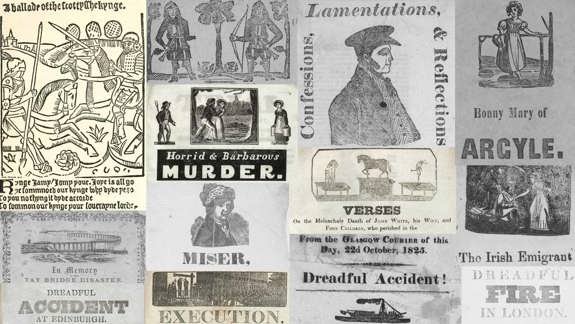

Salacious deeds and disasters

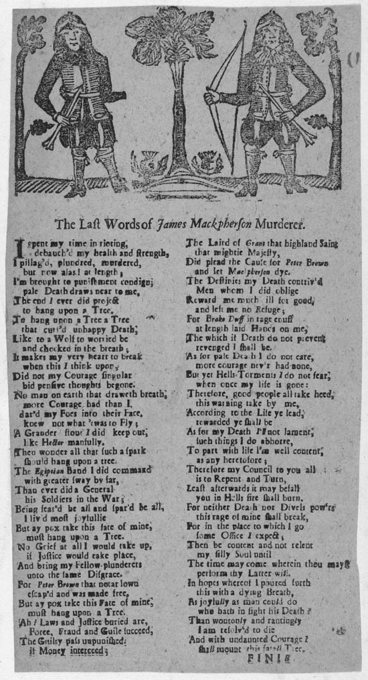

Accounts of murders, descriptions of executions and tales of disaster were the most popular broadsides. Like stories from sensationalist news outlets today, reports of dark and salacious deeds sold in large numbers. To sell as many copies as possible, broadside printers competed to bring people this news almost as it was happening.

For printers, crimes had the added bonus of generating sequences of sheets. For instance, a single murder might lead to separate broadsheets on the discovery of the body, the investigation, the trial, the execution of the guilty party and transcriptions of their final words. Printing in sequences like this gave printers and hawkers multiple opportunities to make money from the same story.

Broadside authors could position themselves themselves as moral guardians and teachers in society. As such, publishers often disseminated 'educational' texts outlining the social and personal consequences of undisciplined or immoral behaviour. Many of the reported scaffold speeches and confessions were purely imaginary. In these interpretations, the criminal usually gave a brief life history, describing how they fell into a life of crime. Finally, they appealed for forgiveness and urged readers to live upright lives.

People have always had an insatiable appetite for accounts of tragedies and disasters too. Shipwrecks, floods, fires and terrorist outrages still make front-page news today. Broadsides about such subjects were equally popular. Human interest stories, sometimes touching or heroic, sometimes farcical or bizarre, were less popular, but were still carried regularly on broadsides.

Humour and marvels

Many broadsides had a strong thread of humour – not to mention satire – running through them. Some focused on women's role in society or the latest fashions, while others parodied current affairs.

"Now all you young ladies I pray you beware,

Of all the young men that would you ensnare;

For when you discard them by word or by note,

They'll declare they've been hooped by your petticoat."

Verse from 'Answer to Ladies Crinolines', 1850s

Readers were also captivated by strange tales of child prodigies, mermaids and the like. Two hundred years ago, many would have believed stories we might find fantastical today.

Getting the word out

Glasgow, and in particular the Saltmarket, was the heart of production and distribution for Scottish broadsides. For printers like Robert MacIntosh, James Lindsay and Matthew Leitch, broadsides were the mainstay of their business. A catalogue of Lindsay's from 1856 lists no fewer than 200 'slips' (narrow sheets) each featuring two songs.

Many of the printers who produced broadsides also printed booklets, playbills and pamphlets of love songs known as garlands. Though some sold directly to the public, most relied on street sellers like pedlars and hawkers to distribute their work. Buying broadsides from printers in urban centres like Glasgow, Edinburgh, Falkirk and Stirling, these sellers went from door to door with the latest publications, or sang or shouted about them on the city streets. They also carried them to markets and fairs throughout Scotland.

Hawkers were street performers in their own right and many were celebrated in print by their contemporaries. These include William Cameron, known as 'Hawkie', who sold broadsides in Glasgow.

Broadsheet illustrations

Originally just single sheets of paper, broadsides sometimes included crude woodcut illustrations, intended to grab attention.

Woodcuts are the earliest form of printed illustration, first used in the mid-1400s. They are made by drawing a reverse image of the final illustration on a block of wood and gouging away the sections that won't be printed.

Putting an illustration in a broadside increased its perceived value, especially among people who couldn't read. Printers worked on the assumption that the more images on a sheet, and the larger they were, the more copies they would sell. To keep costs down, they kept a limited stock of carved woodblocks, which they reused again and again. In many cases, the illustrations therefore bore little or no relation to the text.

Why did broadsides die out?

The mechanisation of the printing industry in the early 1800s saw a phenomenal increase in all types of street literature, including broadsides. Newspapers had been around since the mid-1600s but were, at that time, only read by a privileged few.

However, when the tax on newspapers was removed in 1855, they became affordable for the working classes. By then, the penny that previously bought you a single broadside ballad could buy an instalment of a sensational 'penny dreadful' novel, a cheap newspaper or an entire weekly magazine.

Dive deeper

Word on the Street

Printing and publishing