Stories

Read stories about or inspired by our collections, exploring the language, literature, people, and places of Scotland and beyond.

New

Sentenced and silenced: The criminalisation and transportation of queer lives

Discover how 19th-century Scottish law silenced queer voices and controlled identity through class, power, and punishment.

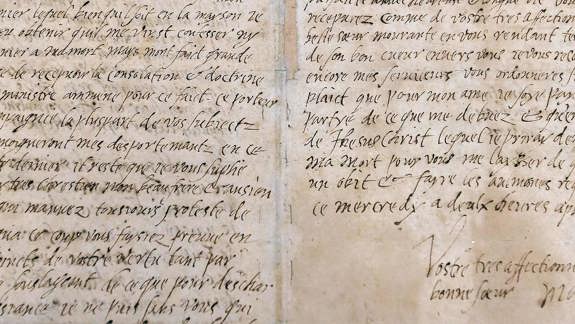

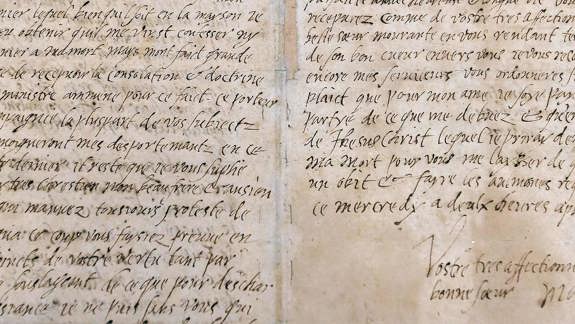

The last letter of Mary, Queen of Scots

Read about the emotional farewell from a queen who claimed martyrdom and a rightful crown.

Mary Shelley and the Scottish Gothic Tradition

Read about the profound impact Mary Shelley's 'Frankenstein' has had on literature and culture.

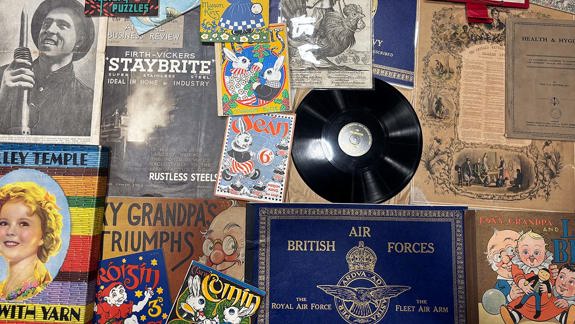

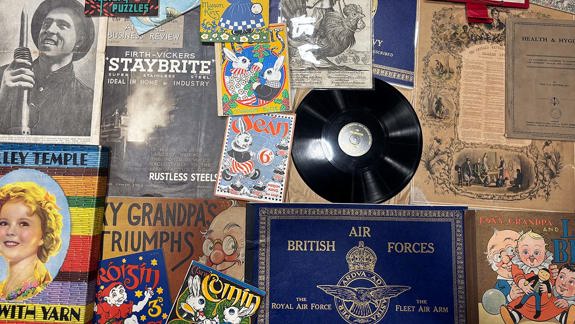

From morse code to Shirley Temple: Unboxing hidden collections

Why did 17th-century Royal Proclamations share a box with Foxy Grandpa comics? Uncover the mystery of the Library’s unusual ‘Series 7 collection’.

Scottish history

Explore the historic events and moments that have shaped ScotlandThe last letter of Mary, Queen of Scots

Read about the emotional farewell from a queen who claimed martyrdom and a rightful crown.

James VI and I: A life and reign in 10 parties

Explore the extravagant parties thrown by James VI and I and be amazed by tales of opulence and royal festivities.

How Martin Luther sparked the reformation

Martin Luther, a little-known monk, sparked a revolution with a theological debate, changing history and facing severe consequences.

Literature and poetry

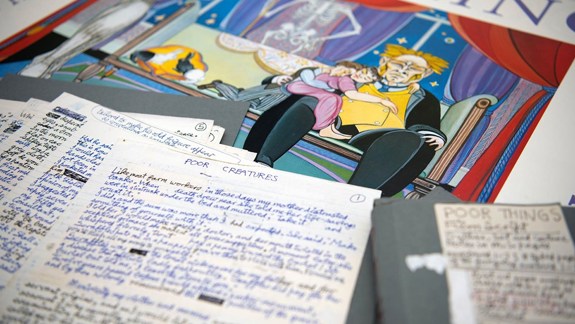

Read more about Scotland’s literary legacy'Poor things': Alasdair Gray's postmodern classic

Manuscripts Curator Colin McIlroy explores the mind and inspiration behind the story on which the film 'Poor Things' was based.

Mary Shelley and the Scottish Gothic Tradition

Read about the profound impact Mary Shelley's 'Frankenstein' has had on literature and culture.

Lewis Grassic Gibbon and 'Sunset Song'

We explore Gibbon's life, drawing links between 'Sunset Song's main character and the writer's conflicted feelings about his childhood home.

Moving image

Read stories about our archive of moving imagesOutlander's Scotland: Myth, romance and adventure in the Scottish film archive

Inspired by the television series 'Outlander', join us on a time-travelling tour of Scotland on film through our moving image collections.

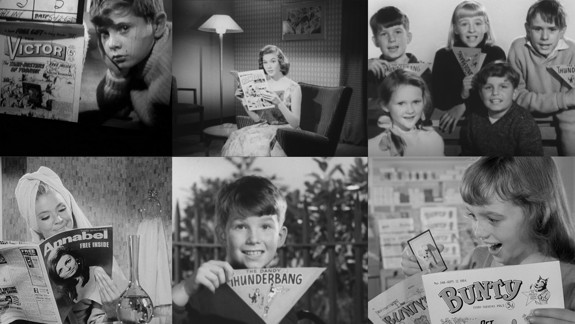

Rust to riches: DC Thomson's forgotten vintage adverts

A 'treasure trove' has brought collections to light and revealed new information about the history of Dundee-based media company DC Thomson.

Printing and publishing

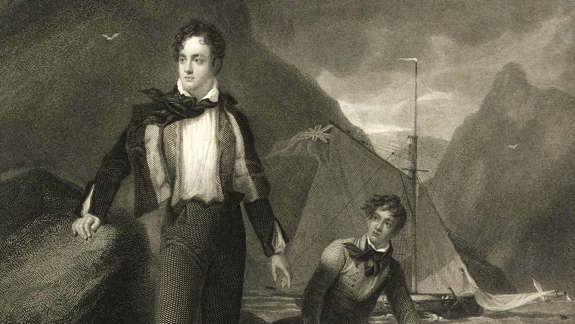

Explore Scotland's publishing evolutionLord Byron's 'impossible' manuscript: 'Don Juan'

Byron's wild fame worried his publisher. Curator Kirsty McHugh explores how their bond shaped 'Don Juan' and Byron's legacy.

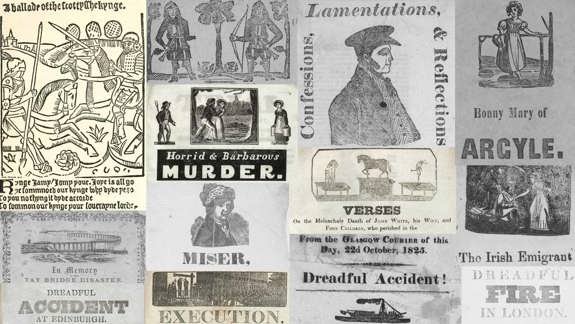

Scottish Broadsides: Three centuries of news and views

Before social media, broadsides—cheap printed sheets—were the main source of news, songs, and speeches for nearly 300 years.

'The Scotsman': From underground newspaper to Scottish institution

Once underground in 1817, The Scotsman grew into a national voice. Explore its origins and insights from its historic pages.

Society and politics

Explore social and political forces that have shaped public lifeSentenced and silenced: The criminalisation and transportation of queer lives

Discover how 19th-century Scottish law silenced queer voices and controlled identity through class, power, and punishment.

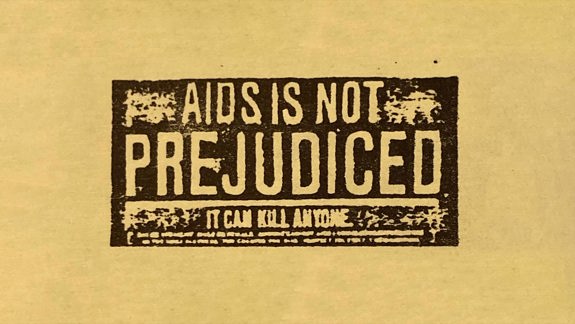

From stigma to strength: The evolution of HIV and AIDS awareness

Our collections reveal Scotland’s complex HIV and AIDS history.

Art and design

Read our stories about art and designEsther Inglis: Renaissance calligraphy, art, and diplomacy

Explore the remarkable story of Esther Inglis, whose talents range from calligraphy, visual arts, poetry, and international relations.

Unveiling LGBTQ+ treasures through the Glasgay! arts festival

Discover how a Glasgay! postcard sparked a powerful reflection on queer identity, memory, and belonging.

Sports and recreation

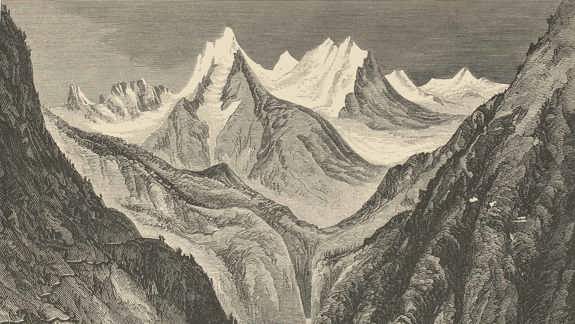

Dive into Scotland’s rich sporting history, from golf to mountaineeringPioneering mountain women

19th to 20th century women climbers needed grit—not just for peaks, but to defy societal norms that doubted their place in mountaineering.

Life in the Library

Behind the scenes of the LibraryFrom morse code to Shirley Temple: Unboxing hidden collections

Why did 17th-century Royal Proclamations share a box with Foxy Grandpa comics? Uncover the mystery of the Library’s unusual ‘Series 7 collection’.

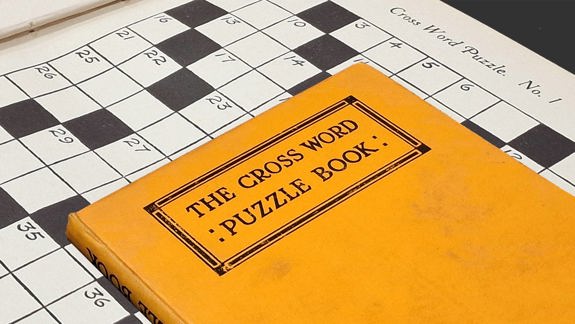

From clues to collections: A puzzle in the Library

The delicate balance between engagement and preservation explored through puzzles.

Archive detectives: Tracing family history clue by clue

Liz Carter takes us on a journey of discovery via an enquiry she recently worked on.

Support your national Library

Your donation preserves Scotland's rich heritage, ensuring that our world-renowned resources remain accessible to future generations. Every gift, large or small, makes a difference.

Donate today