Robert Adam: The aspirational architect inspired by ancient Rome

Introduction

Robert Adam was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife in 1728. His father William was a stonemason and architect. Though his brothers, John and James, followed in their father's footsteps too, it was Robert who went on to become the most famous Scottish architect of his generation. His unique style revolutionised the look of affluent homes and public buildings thanks to inventive combinations of elements from classical Roman architecture.

Early influences: from school Latin to an impenetrable fortress

Adam first became immersed in the culture of Ancient Rome while receiving a Latin education at Edinburgh High School. Later, he also studied at Edinburgh University. Outside his formal education, Adam encountered Enlightenment ideas thanks to his family's social circle. As a result, he embraced reason, independence, inquisitiveness, practicality and common sense.

Adam had wanted to be a painter, and it's likely he studied drawing in Edinburgh. However, Adam became an assistant to his father, and, when William died two years later, Robert took on the family business with his older brother, John.

The Adam brothers together worked on a number of Highland forts for the Crown after the Jacobite rising in 1745. In 1748, as Royal Master Masons, they were also involved in the construction of Fort George just outside Inverness. The new fortress was intended to quash any future rebellions and housed 1600 infantryman. Building such an imposing military base was a major undertaking, which gave young Adam an excellent grounding in the fundamentals of construction.

Adam's Grand Tour

Despite working on major contracts like Fort George, in the 1700s architects were, like builders, considered tradesmen. Keen to rise above this view, Adam wanted to educate himself in the art of drawing and learn about the architecture of the classical world. So, aged 26, he set off on the 'Grand Tour'. This journey through France, Italy and wider Europe, was a popular rite of passage for many aristocratic young men of the time.

In October 1754 Adam sailed from Dover to Calais, travelling with the son of a Scottish earl. The pair journeyed through France, Belgium and the Netherlands visiting churches, palaces and Roman ruins. Along the way Adam bought velvet and satin clothes, lace cuffs and silk waistcoats.

At the end of January, they arrived in Florence, Italy, where Adam met the architect and draughtsman Charles-Louis Clérisseau. Adam was so taken with Clérisseau's work that he engaged him as a tutor to develop his perspective drawing and watercolour skills and his knowledge of antiquities. When Adam travelled south to Rome, he brought Clérisseau with him.

Adam stayed in Rome for two years. He studied and drew every day and went on sketching expeditions with Clérisseau and the Italian classical archaeologist Giovanni Batista Piranesi. Describing himself as "antique mad", Adam collected drawings, bought books, employed others to draw or paint architectural details and produced casts of ornaments in palaces and churches. He hoped, he wrote, "to have my ideas greatly enlarged and my taste formed upon the solid foundation of genuine antiquity".

Diocletian's Palace

Adam found particular inspiration when he travelled to Spalato, now named Split in present-day Croatia. There he visited the ruined Palace of the Roman Emperor Diocletian, which dated back to the fourth century AD.

"The buildings of the Ancients… serve as models which we should imitate, and as standards by which we ought to judge."

Robert Adam in 'Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia'

The palace hadn't previously been studied, so if Adam published his own research on the site, he had an opportunity to establish his scholarly reputation as an architect. After conducting a detailed survey of the Palace, Adam embarked on a project to share his findings in an illustrated book. He devoted several years to the task, working with his brother James and two teams of artists. One team was based in Venice, the other in London.

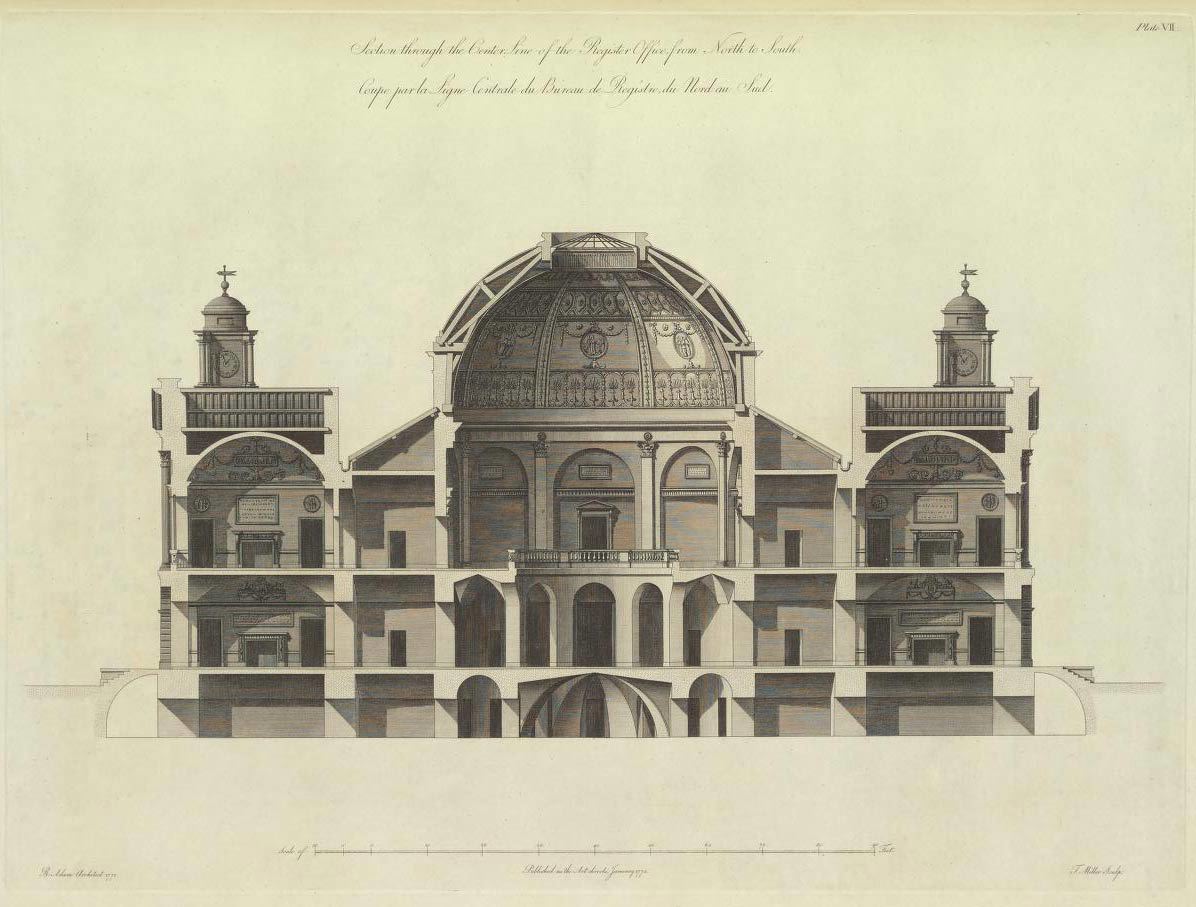

When the book was finally published in 1764, its 61 illustrations included both picturesque views and conventional architectural drawings. Though Adam's reputation was, by then, growing, the publication provided tangible evidence of his links with the architecture of Ancient Rome.

Developing the Adam style

Adam's time in Italy and Spalato influenced his work for the rest of his career. By observing Roman design, he learned to blend the architecture of the ancient world with his own inspirations. The contacts he made while travelling helped him establish an office in London.

"We have been able to seize, with some degree of success, the beautiful spirit of antiquity, and to transfuse it, with novelty and variety, through all our numerous works."

Robert Adam in 'The Works in Architecture'

Just as importantly, he now had the confidence to develop beyond the confines of what it meant to be an architect in the 18th century. Taking classical Roman designs and interpreting them with a light, modern twist, he created country houses that looked like castles and terraced homes disguised as palaces. Paying as much attention to a building's interior and furnishings as its external structure, Adam became known for his elegant, decorative style.

The concept of 'movement' was an essential component of Adam's work. For him, the ways in which parts of a building rise, fall, advance and recede mimic the hills, dales, foreground and depth of a landscape painting. By creating a variety of light and shade in both landscapes and architecture, movement, said Adam, "gives great spirit, beauty and effect to the composition".

Coming close to ruin

Despite receiving commissions to remodel or adapt grand country houses in the 1760s, Adam was disappointed not to win public commissions that would signal his high status. He was appointed as joint architect of the King's Works in 1761, which should have led to big commissions in England, but he was effectively excluded from high-profile commissions at the Royal palaces. To fill the gap, Adam focused on expanding his Scottish practice and on speculative building projects. One such project almost ruined him.

In 1768 the brothers embarked on the huge Adelphi scheme, an unprecedented speculative building venture by the Thames in London. They leased a site, borrowed money to fund construction and built an elevated terrace of 22 private houses. The space below was intended to be to let as riverside warehouses. However, the warehouses proved difficult to let and a national credit crisis led the brothers to abandon the project. The failure of the Adelphi was a financial disaster, which also brought negative attention onto the firm.

'The Works in Architecture'

To re-establish themselves and their reputations, the Adam brothers took on another ambitious project. Not long after the Adelphi scheme failed, on 16 January 1773, Robert and James Adam announced the publication of a new book.

'The Works in Architecture' featured designs for public buildings, the homes of aristocrats like the Duke of Northumberland, the Earl of Mansfield and the Earl of Bute, and commissions for the King and Queen. Strapped for cash, the brothers issued the 'Works' in parts rather than publishing the book outright. This enabled them to avoid a lengthy fundraising process to cover the production costs. Despite their financial situation, however. they didn't skimp on quality.

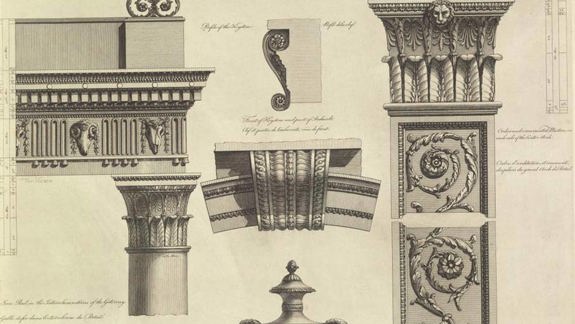

'The Works' was the most lavish display of architecture ever commissioned. Some of the finest engravers of the day were hired to produce plates for the illustrations. Architectural plans, interiors, fireplaces and more were rendered in the finest detail. Every kind of ornamental furniture was featured – from candlesticks and clock cases to sedan chairs and harpsichords. In a new and bold approach, each illustrated page showed a mixture of individual elements. Chimney-pieces and decorative details might therefore appear together, in a pleasing, balanced composition.

As with Adam's earlier book on Diocletian's Palace, the project took years to complete. With the final part publishing in 1778, 'The Works in Architecture' transformed the brothers' reputation and established the Adam style in Britain and beyond. Today it's regarded as one of the finest architectural books of the 18th century.

"There is an air of grandeur, as well as beauty, in many of the plans…joined to a freedom of invention, which is the great characteristic of genius."

Extract from a review of 'The Works in Architecture' in 'The Monthly Review', (page 451, Volume 49, 1773)

Returning to Scotland

As Adam's elegant and endlessly varied decorative schemes became the very height of British fashion, he balanced a successful country house practice with the public commissions he had long sought.

Though Adam maintained a base in London, by the 1780s, much of his work was in Scotland. His account book for the year 1791-2 shows projects stretching across Scotland, which he largely managed himself. In Edinburgh, he revisited the conceptual grandeur of the failed Adelphi scheme in the prime New Town development of Charlotte Square. His designs there included a terrace of houses fronted by a symmetrical, neoclassical palace facade. In Glasgow, he designed the Royal Infirmary.

When Adam died in 1792, he might justifiably have claimed that his work – and his efforts to bolster his reputation – had set him apart not just from tradesmen, but from other architects. What he termed "a kind of revolution in the whole system" of architecture – particularly in interior decoration – was widely imitated at the time. Today, his designs are still studied, admired and revisited.

Dive deeper

Archives and manuscripts catalogue

Art and design