Muriel Spark: People-watcher, traveller, novelist

Introduction

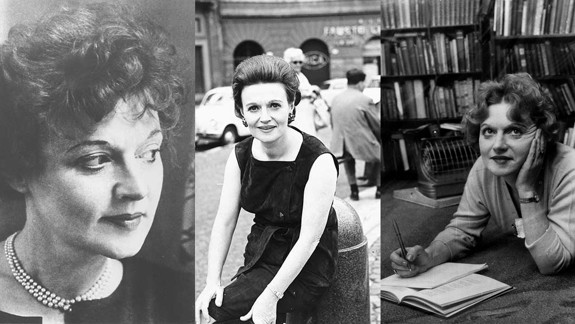

Who was Muriel Spark?

Muriel Spark was a Scottish poet, novelist and literary biographer. Though best-known for her 1961 novel 'The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie', she wrote 21 other novels, published poetry collections and produced critical editions of the work of several classic writers.

Spark blended the supernatural and the real, the comic and the tragic, satire and allegory. Her unique works helped change the face of fiction in the English language and she sat at the top of her profession for over half a century.

Born Muriel Camberg in Bruntsfield in Edinburgh on 1 February 1918, Spark later lived in Zimbabwe, London, New York, Rome and Tuscany. Each location delivered new experiences that inspired Spark's poetry and fiction.

In the 1940s, Spark began to keep a record of her professional and personal activities, which she transported with her as she moved around the world. Now held by the National Library of Scotland, this archive gives insights into how Spark's own life influenced her writing.

Edinburgh and the real-life Miss Jean Brodie

As a girl, Spark attended what was then James Gillespie's High School for Girls in Edinburgh. She considered this a most fortunate experience for a future writer. Bright and hardworking, Spark became known at school as a poet and a dreamer. She later wrote that she was "far more interested in the looks, the clothes, the gestures" of her teachers than in what they were teaching. It was an early sign of Spark's lifelong interest in observing people and their behaviour.

When Spark was just 12, five of her poems appeared in the school magazine. Two years later she was crowned the school's 'Queen of Poetry'. Poems from this time are the earliest manuscripts to be found in her archive. One includes a note from Spark saying, "Very early works. Take with pinch of salt (and double gin)".

Gillespie's High School provided the model for the Marcia Blaine School that features in Spark's most popular novel, 'The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie'. In the book, the charismatic schoolmistress Jean Brodie introduces pupils to "the order of the great subjects of life … art and religion first, then philosophy; lastly science". But while Brodie is "an Edinburgh Festival all on her own", she also admires Mussolini and fascism.

Spark's teacher, Christina Kay, was the inspiration for Brodie. Although the unconventional fictional character differed from her real-life model, Spark felt that Miss Kay "had it in her, unrealised, to be the character I invented".

Economical prose and people watching

After leaving school, Spark took a précis-writing course at Heriot-Watt College. She later said of these classes, "I love economical prose, and would always try to find the briefest way to express a meaning". Sparse and exact writing would become a hallmark of Spark's style.

Following a short spell teaching English, Spark worked as a secretary in William Small's elegant department store in Edinburgh's Princes Street. Here she sharpened her talent for observing characters – from condescending shoppers to flattering saleswomen.

Zimbabwe and 'The Seraph and the Zambesi'

In August 1937, the young Muriel Camberg travelled to Africa to marry Sydney Oswald Spark, who had taken up a teaching post in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). On the two-week sea journey to Cape Town, the bride-to-be wrote the first of a trail of evocative poems that trace her voyage and her African travels.

Spark was just 19 years old when she arrived in Africa and her life there was far from happy. She later described herself as, "really very young and rather dumb". Less than a year later, Spark gave birth to a son, Robin, but her marriage was failing and she longed to leave Africa.

After the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, travel became difficult. Spark had to wait until 1944 before she could secure passage on a troop ship bound for Liverpool.

During these difficult years, Spark carried on writing. Taking inspiration from her experiences, she collected memorable settings and characters she would return to in later work. Africa itself provided a refuge of sorts from her personal troubles and a visit to the Zambezi River proved particularly inspirational.

Spark later reflected, "The experience of the Victoria Falls gave me courage to endure the difficult years to come. The falls became to me a symbol of spiritual strength… They are one of those works of nature that cannot be distinguished from a sublime work of art". She expressed her feelings in poetry and a short story called, 'The Seraph and the Zambesi'. The latter would go on to change Spark's fortunes for the better.

London and 'The Poetry Review'

Finally arriving back in England in 1944, Spark was fortunate to gain a wartime post in political intelligence at MI6. She worked at Milton Bryan in Bedfordshire, which she later fictionalised as 'The Compound' in her novel 'The Hothouse by the East River'. Working in wartime black propaganda proved to be a central influence on Spark's fiction style. However, in the years immediately after the Second World War, Spark dedicated herself not to fiction, but to poetry.

From 1944 to 1962, Spark lived in London. She flitted between bedsits and flats and later evoked her London bedsit lifestyle, complete with struggling writers and shifty publishers, in 'A Far Cry from Kensington', which published in 1988.

During her time in London, Spark maintained a consistently high work-rate in an effort to establish herself as a writer. When peace came in 1945, Spark began an apprenticeship as a journalist at 'Argentor', the official journal of the National Jewellers' Association. She began to write seriously and, in 1947, became editor of 'The Poetry Review'. Not long after, Spark had built a reputation as an editor, critic and poet.

The first poetry collection

Spark left the Poetry Society after numerous disagreements, including one over her policy of publishing new writers. Her own writing was becoming more important by then and established authors like Graham Greene were among her supporters. This turning point in Spark's life was the moment when she decided to create her archive.

Spark's first collection of poems, 'The Fanfarlo and Other Verse', published in 1952. Alongside her own writing, she completed extensive reading and research on authors like Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Emily Brontë, William Wordsworth, and John Masefield. In just four years, she brought out seven critical studies and editions of their work.

These same research skills became useful later, as Spark explored topics and settings for her novels. For instance, when working on 'Reality and Dreams', a novel about a controlling film director, Spark consulted books on make-up and special effects and read titles like, 'On Filmmaking', 'Filmmaking Foundations' and 'The Film Director as Superstar'.

Before 'The Fanfarlo and Other Verse' was published, Spark submitted the short story she had conceived in Africa to 'The Observer' newspaper's short-fiction competition. 'The Seraph and The Zambesi' triumphed over 6,700 others to take first prize. This success stimulated Spark to write more and longer fiction.

'The Comforters'

In 1953 Spark, who had Jewish heritage, was baptised in the Church of England. A year later, she converted to Catholicism. Around this time she experienced a breakdown brought on by malnutrition and use of the appetite suppressant Dexedrine. Spark's hallucinatory experiences during the episode served as material for her first novel, 'The Comforters'.

Published in 1957, 'The Comforters' fictionalised Spark's breakdown, mixing realism with elements of theology, psychology and the supernatural. Set mainly in a sleepy Sussex coastal village, the novel is also a satirical evocation of the London literary scene of bedsits, poets, and pubs. A diamond-smuggling grandmother, a comic diabolist and a typing ghost all feature, giving an early indication of Spark's breadth of vision.

'The Comforters' received rapturous reviews, including one from the writer Evelyn Waugh. On publication day, Spark's editor telephoned her and said, "You've hit the jackpot today".

So began a string of six novels, which Spark produced within five years. 'Robinson' came next, followed by 'Memento Mori', 'The Ballad of Peckham Rye', 'The Bachelors' and, in 1961, 'The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie'.

The following year Spark visited New York to mark the American publication of the Brodie novel. She was treated in such style that later the same year she returned to the city for the first of several extended stays.

New York and 'The Mandelbaum Gate'

Spark's years in New York represent a dazzling spell in her life. She rented a suite at the Beaux-Arts Hotel and was given her own corner office at 'The New Yorker' magazine. Keeping a room in London, Spark became a jetsetter, journeying back and forth between the two cities.

Fêted by publishers, fellow writers and artists, Spark enthusiastically embraced the Manhattan social scene. She enjoyed rounds of parties, lunches and other entertainments with an ever-increasing circle of friends. These included renowned writers like James Baldwin, WH Auden, Norman Mailer, Shirley Hazzard and John Updike.

Despite her busy social calendar, Spark still found time to write two further novels, 'The Girls of Slender Means', set in wartime London, and the prize-winning 'The Mandelbaum Gate'. This story of a woman's pilgrimage to the Holy Land tackled Spark's broadest themes to date, from international espionage to the blurring of personal, religious, and political boundaries. Harold Macmillan, the former British Prime Minister then helming Macmillan publishers, described the novel as "by far the best book you have written". In 1966, it won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

By then, 'The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie' had been adapted for the theatre with Vanessa Redgrave heading the cast in the first London production. Three years later the story was made into a film starring Maggie Smith, who won the Best Actress Oscar in 1969. The following day Smith telegrammed Spark to thank her "for creating such a wonderful character for me to play".

Before the stage version transferred to Broadway in 1968, Spark – now comfortable due to her earnings from writing – chose to move on. She was at the peak of her career, and Italy beckoned.

Rome and 'The Driver's Seat'

Spark's love affair with Rome began in 1966, and she settled there in 1967. As she had done in New York, she balanced a party lifestyle with a literary output of the highest order.

Rome was, at that time, home to a considerable number of Britons and Americans and Spark enjoyed the City's cultural pursuits and social engagements. Following a Spark party in Rome, Miriam Margolyes, who starred in the BBC's adaptation of 'The Girls of Slender Means', described the event as, "infinitely glamorous, socially devastating, for I have never met all in one go such a number of distinguished people".

The Rome years show Spark in her most experimental phase. 'The Driver's Seat', published in 1970, was her most shocking work and her personal favourite. This creepy, present-tense novel spans the last terrible day of an office worker heading off for the holiday of a lifetime. It was later filmed starring Elizabeth Taylor.

Spark produced 'The Hothouse by the East River' around the same time, a striking, uneasy tale with a twist. Set in New York, the book also features a war-time British Intelligence base, based on Spark's time with MI6. She drew on her experiences at the Poetry Society in 'Loitering with Intent' and riffed off newsworthy world events to fashion the comic masterwork 'The Abbess of Crewe'. The latter offered a wonderfully reductive comic distillation of the Watergate scandal, imaginatively transposed to a convent in Cheshire. Once again, this was adapted for cinema, with Glenda Jackson in the leading role.

Tuscany and 'Curriculum Vitae'

From 1975 onwards, Muriel Spark spent much of her time in Tuscany. By 1985, a converted farmhouse beside a 13th-century church became her permanent residence.

Spark lived in the home of her closest friend, Penelope Jardine. Surrounded by books, cats, and olive groves, she enjoyed the relative peace and quiet. Though no longer partying as she had done in New York and Rome, she continued to release a steady stream of memorable characters and striking stories into the literary world.

In Tuscany, Spark wrote five novels, more poetry and even – briefly – an online diary. In 1992, she brought out her extensively researched autobiography 'Curriculum Vitae'. Covering the period from her upbringing in Edinburgh to the publication of her first novel in 1957, Spark only included the memories she could verify through eye witnesses, documents or letters. Her archive was therefore a key source of information.

"One thing I have always known about my well-ordered archive is that it would stand by me, the silent, objective evidence of truth, should I ever need it".

Muriel Spark writing in 'Curriculum Vitae'

In 'Curriculum Vitae' Spark recounts meeting poet John Masefield in 1950, when he told her, "all experience is good for an artist". She says she was always aware of gaining experience "for some future literary work" and she never overlooked any experience, even those that were difficult. "Most of the memorable experiences of my life", she says, "were celebrated or used for the background of a story or novel."

Writing processes and 'The Finishing School'

In 2004, Spark published a volume of poetry that spanned her writing career and her last novel, 'The Finishing School', which takes a wonderfully satirical look at creative writing in the classroom.

From her own perspective, Spark felt the study and practice of all types of verse forms had given her a sense of how to manipulate language and organise sentences for effect. As she wrote in an essay on the topic, she felt strongly that there was "more to creative writing than just to sit down to write and simply vent your feelings".

Like many writers, Spark had very specific writing habits. She wrote the first drafts of all her novels by hand. She only wrote with pens that had never been used by anyone else. And she had a fondness for specific spiral-bound lined notebooks sold by Edinburgh stationer James Thin.

When drafting a novel, Spark only used the right-hand side of these notebooks. The facing pages were left empty for potential revisions. Even when living overseas, Spark requested and used these exact notebooks. Aside from feeling familiar, the notebooks imposed practical constraints on Spark's writing. For instance, most of her novels take up five James Thin notebooks and the story usually concludes at the very end of the fifth.

Once ordering 48 in one go, Spark became so dependent on these notebooks that when Thin discontinued them in the early 90s, she contacted the company. In response, Thin produced custom-made notebooks for their keenest customer.

Legacy and lasting influence

Spark's friend and living companion, the painter and sculptor Penelope Jardine, proofread her drafts, revisions and final proof copies. Though Jardine’s editorial interventions were relatively minimal, she performed dedicated work behind the scenes. For instance, Jardine made suggestions for book blurbs and compiled character lists that kept track of people's appearances and actions through each book.

Jardine organised Spark's archive and has often been described as Spark's 'secretary'. However, Jardine's role stretched beyond this. The kind of care and support she bestowed on Spark’s work reflects the enthusiasm and thorough inspection of a fellow artist.

Spark died in Florence, aged 88, in April 2006, leaving her 23rd novel unfinished. During her career, she received numerous awards, beginning with the prestigious Italia Prize in 1962 for an adaptation of 'The Ballad of Peckham Rye'. She received many honorary degrees and became a Dame Commander of the British Empire in 1993. In addition, hundreds of fan letters in the Muriel Spark archive at the National Library of Scotland are testament to the popularity of her books.

In 2018, on the centenary of her birth, the Scottish Government announced that every public library in Scotland would receive a complete collection of Spark's novels. The gift was a fitting tribute to a writer who the then CEO of Scottish Book Trust described as "a giant of 20th century literature – a singular person, and an iconic, iconoclastic and brilliantly rebellious female genius".

Dive deeper

See more Muriel Spark online

Muriel Spark archive