Sir Walter Scott and his historical influences

Introduction

Who was Sir Walter Scott?

Sir Walter Scott was a poet, novelist, editor, critic and historian. The cultural icon of his age, Scott was instrumental in developing and popularising the historical novel.

Scott was born in Edinburgh in 1771. The son of a solicitor, he contracted polio as a toddler and was sent to live on his grandparents' farm in the Borders for his health. Here, he first encountered stories about Scottish history. He listened to tales of border battles shared by his grandmother and traditional songs read by his aunt. For most of the period 1773 to 1778 Scott lived at the farm, apart from about a year spent in Bath. He was taken there by his aunt Janet Scott in the middle of 1775, where he learned to read at a dame school.

By the age of 12, Scott read Shakespeare, Milton, works of history and Thomas Percy's 'Reliques of Ancient English Poetry'. After attending the University of Edinburgh, he began five years of training to be a solicitor, an experience he once described as a "dry and barren wilderness". He secretly read adventure books in the office. Outside work he took trips with friends to visit sites of historical interest.

Scott the writer

An antiquarian who loved collecting and browsing historical sources, Scott was also an exceptional storyteller. He published a collection of Border ballads in 1802, but first gained a reputation as a writer thanks to works like 'The Lay of the Last Minstrel'. Set in the Scottish Borders in the mid-16th century, this narrative poem combined experimental verse with traditional balladry. 'The Lay' was published to critical acclaim in 1805 and Scott followed it up with more narrative poetry.

Today, Scott is better known as a novelist. His first novel came about after he pondered how best to preserve the story of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. Undecided about whether this should be done "by collecting the old tales or by modernising them", Scott combined both approaches. In the process, he helped shape and popularise the modern historical novel.

Scott set his historical books around recognisable, real events and populated them with fictional characters who interacted with known historical figures. Often focusing on conflicts between the haves and have nots, he transformed the facts of history into dramatic, imaginative accounts of what might, could or should have happened.

In every new book, Scott experimented with a new literary device. He employed different types of narrators, placed both men and women centre-stage and created collages of alternative points of view by combining direct speech, journal entries and letters. These techniques enabled Scott to represent multiple views of the past, including the perspectives of people from different classes.

Scott's first novel

The hero of Scott's first novel, Edward Waverley, is a young Englishman who arrives in Scotland just before the Jacobite Rising. Set in locations from London to the Highlands, the story brings to life characters on both sides of the conflict. A quotation from Shakespeare's 'Henry IV' Part II included on the title page gives an early hint of Waverley's divided loyalties, since he must choose between supporting King George II or the exiled Jacobite, Charles Edward Stuart (sometimes referred to as Bonnie Prince Charlie).

"Under which King, Bezonian? Speak, or die!"

Quote from Henry IV, Part II on the title page of 'Waverley'

Highland sources

When writing the Highland incidents in the novel, Scott drew on a first-hand account of life in the Highlands in the years before the Jacobite Rising. One of his key sources was a collection of letters from the 1720s written by Edmund (also known as Edward) Burt, who worked as a rent collector for the British Government. Scott owned copies of both the first and second editions of Burt's 'Letters from a Gentleman in the North of Scotland to his Friend in London'. It was an important source for Scott when describing incidents of Highland life and culture. Other important sources for the history of the rising include John Home’s 'A history of the rebellion in the year 1745' (1802) and James Ray's 'A compleat history of the Rebellion' (1746).

An almost lost manuscript

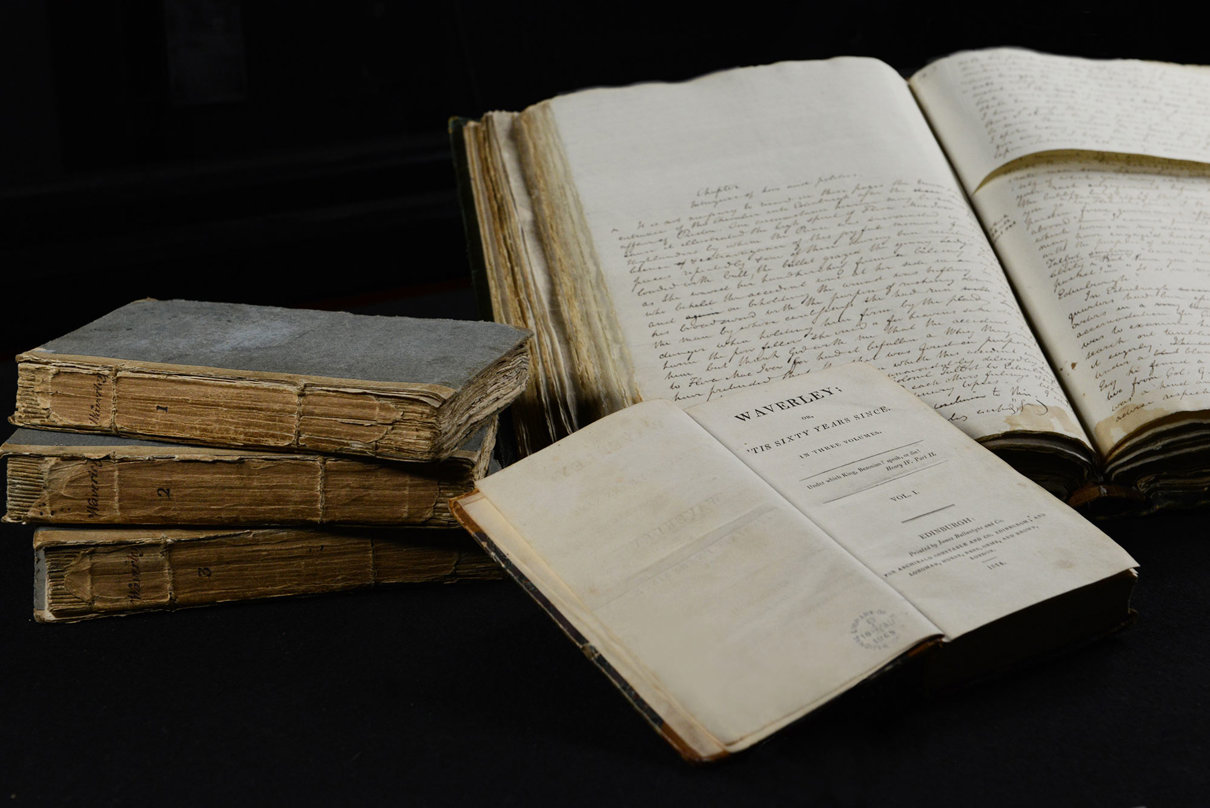

From the manuscript, it's clear that Scott wrote the book in two stages. The surviving first section is on paper watermarked with the year '1805'. However, scholars have compiled evidence that suggests Scott must really have begun to work seriously on the novel a few years later. The second section is on larger paper watermarked '1813'.

Scott drafted the story on the right side of the page, using the left for amendments and rewrites. However, after hearing the "unfavourable opinion" of a "critical friend" about the first seven chapters of the novel, he put the entire manuscript aside in a writing desk. The desk ended up in an attic at Abbotsford, Scott's home in the Scottish Borders. The manuscript might have languished there if it wasn't for Scott rediscovering it one day while rifling through the desk looking for fishing lines and flies.

Publishing to "instantaneous" demand

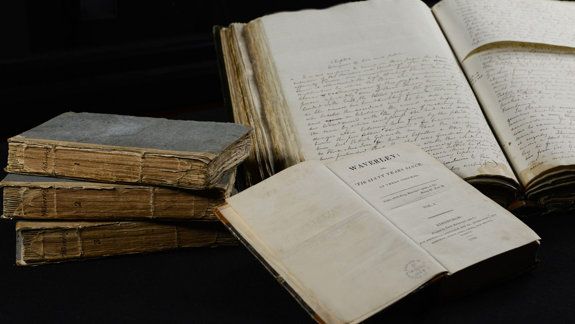

Scott's first novel was published on 7 July 1814. Taking its name from the story's hero, the book was titled, 'Waverley; or, 'Tis sixty years since''.

Priced at one pound, one shilling, 1000 copies were printed. Like most other novels of its day, 'Waverley' was originally published in a modest set of three volumes without illustrations. Scott's publisher Archibald Constable was, however, confident that "the demand for the book will be instantaneous & great".

Scott's fascinating storytelling style and his romantic depiction of the Scottish Highlands caused a sensation. His style of mixing fictional characters with real-life figures in a story set during a familiar historical event proved widely popular. Constable's prediction came true: over 8,000 copies were produced in the following few years.

A not so anonymous author

Walter Scott's name did not appear anywhere in the book and he didn't confirm authorship of 'Waverley', or any of the later 'Waverley' novels, for another 13 years. While this may have been because penning a popular novel wasn't a respectable activity for a lawyer, it was common for novelists to remain anonymous at that time.

To maintain his anonymity, Scott usually passed his manuscripts to someone else, who copied them out in their own handwriting before sending them on to the printers. This was often Scott's friend and literary agent James Ballantyne.

Scott even lied to his own publisher, John Murray, to keep his identity secret. Murray once wrote to Scott congratulating him on his book 'Tales of My Landlord'. Scott was unmoved, replying, "I assure you I have never read a volume of them until they were printed".

Despite Scott's elaborate attempts to stay undercover, the identity of the anonymous author was an open secret. Scott's name was even mentioned in reviews of 'Waverley' in the year the novel came out.

'The Heart of Mid-Lothian'

Scott published five books in the three years after 'Waverley' was published. By 1818 he brought out the four-volume novel 'The Heart of Mid-Lothian'. Named after the Old Tolbooth prison in Edinburgh's Old Town, the novel was once again published anonymously. The ruse this time was that the books derived from stories collected by a fictious schoolmaster named Jedediah Cleishbotham.

As with 'Waverley', Scott found inspiration in real places and historical events. In the opening chapters, he recounts the story of the 1736 Porteous Riots. This historical incident takes its name from the Captain of the Edinburgh City Guard, John Porteous.

During a riot at the hanging of a smuggler, Captain Porteous was accused of ordering his men to fire on civilians, several of whom died. Porteous was brought to trial, imprisoned and sentenced to death. When he was pardoned by the Queen, an angry mob broke into the Old Tolbooth and dragged Porteous to the Grassmarket, where they hanged him themselves.

"[Porteous] sprung from the scaffold, snatched a musket from one of his soldiers, commanded the party to give fire, and … set them the example by discharging his piece, and shooting a man dead on the spot."

Extract from 'The Heart of Mid-Lothian' by Walter Scott

Although Scott used artistic licence to change parts of the historical event, he incorporated eye-witness accounts too. For instance, he wrote that the mob left a guinea on the counter of a shop after they broke in to obtain rope for a noose – a detail several observers reported in real life.

The real-life Jeanie Deans

The main plot of 'The Heart of Mid-Lothian' concerns Jeanie Deans, and her efforts to save her sister Effie, a young girl awaiting trial in the Old Tolbooth. Jeanie believes Effie is innocent of her supposed crime (murdering her own child) and walks from Edinburgh to London to ask the Queen to pardon her sister.

The character of Jeanie was based on a woman named Helen Walker, who had travelled on foot from a village near Dumfries to London hoping to obtain a royal pardon for her younger sister Isobel. Like Effie, Isobel was accused of infanticide. Both the fictional Effie and the real-life Isobel were ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing.

Scott heard about this story in a letter written by a Helen Goldie who had met Walker shortly before she died. Mrs Goldie was so impressed by Walker's "prudence" and "heroic virtue" that she wrote to Scott:

"I once proposed that a small monument should have been erected to commemorate so remarkable a character, but I now prefer leaving it to you to perpetuate her memory in a more durable manner."

Helen Goldie in her letter to Scott, from 'Introductory Essays and Notes' by Andrew Lang as part of 'Waverley Novels' (1893)

While immortalising Walker's tale in 'The Heart of Mid-Lothian', Scott wanted to honour her name more publicly. In 1830, he wrote to the Reverend Dow of the Parish of Irongray, where Walker was buried, offering to pay for a monument to her memory. In the letter, Scott acknowledged the role Walker's actions had played in inspiring his story.

"This stone was erected by the author of Waverley to the memory of Helen Walker who died in the year of God 1791. This humble individual practised in real life the virtues with which fiction has invested the imaginary character of Jeanie Deans."

Inscription on the monument to Helen Walker, written by Walter Scott

Scott continued to produce novels in the 'Waverley' series until his death in 1832. He is buried in Dryburgh Abbey, Berwickshire.

Despite being the most successful writer of his day, Scott has now slipped out of many people's consciousness. While Edinburgh's main station is named after his first novel and the magnificent Scott Monument dominates Princes Street Gardens, his books aren't as popular as they once were. Yet later writers learned from Scott's experimental approaches and he is generally recognised as popularising the genre of historical fiction. His legacy therefore lives on in the historical stories we enjoy today, whether in book form, on television or on film. More importantly, Scott's writing shaped Scotland's national cultural identity – tartan and all.

Dive deeper

Digitised manuscripts

Millgate Union Cataogue of Walter Scott correspondence

Literature and poetry