The seven faces of Robert Louis Stevenson: From sickly child to acclaimed storyteller

Introduction

1. The sickly child

Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson was the only child of civil engineer Thomas Stevenson and Margaret Isabella Balfour, the daughter of a minister. In his book 'Memoirs of Himself', Stevenson described himself as an "intelligent and sickly" child.

"I have three powerful impressions of childhood: my sufferings when I was sick, my delights in convalescence at my grandfather's manse of Colinton, near Edinburgh, and the unnatural activity of my mind after I was in bed at night."

Robert Louis Stevenson in 'Memoirs of Himself'

Stevenson's devoted childhood nurse fed the young boy's imagination with stories from the Bible and Scottish history. These tales later inspired novels full of adventure and romance, like 'Kidnapped', 'The Master of Ballantrae' and 'Weir of Hermiston'.

2. The aspiring Bohemian

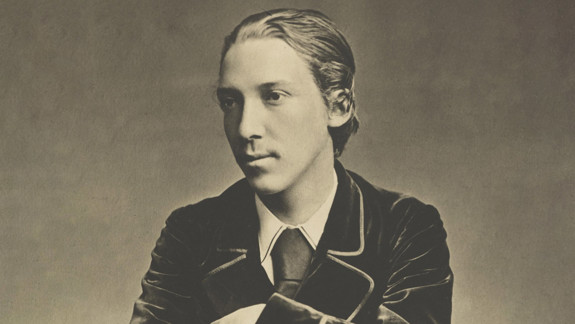

As he grew up, Stevenson rebelled against the conventions of middle-class Edinburgh society. He changed the spelling of his name from 'Lewis' to the French form, 'Louis'. He wore a distinctive velvet coat. And he left Edinburgh's New Town for the Old in search of Bohemianism and adventure.

Hopes that Stevenson would enter the family engineering firm were abandoned on the grounds of poor health. Instead, he qualified as a lawyer, though he never practised law. What Stevenson really wanted to do was write.

"All through my boyhood and youth, I was known and pointed out for the pattern of an idler; and yet I was always busy on my own private end, which was to learn to write… As I walked, my mind was busy fitting what I saw with appropriate words."

Robert Louis Stevenson in 'Memories and Portraits'

'Robert Louis Stevenson, 1850 - 1894. Essayist, poet and novelist' by John Moffat. (Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland)

3. The traveller

The ill health that dogged Stevenson for most of his life had a profound effect on his work and living arrangements. Even short periods spent in the "meteorological purgatory" of Edinburgh affected Stevenson's health, so he spent much of his life in search of more amenable climates.

As a young man, Stevenson tramped around the outskirts of Edinburgh. He also visited the fashionable health resorts of the French Riviera with his parents. He loved travelling and went on to undertake quite strenuous journeys, even when in poor health.

Aged 26, he canoed through the rivers and canals of Belgium and north-east France with friend and regular travel companion Walter Simpson. While providing material for his first travel book, 'An Inland Voyage', the trip led Stevenson to Grez, a Bohemian artists' colony, 70km south of Paris. Here, Stevenson met his future wife, the American Fanny Vandegrift Osbourne. She had travelled to France to escape an unhappy marriage and study art.

Two years later, Stevenson walked through the Cévennes mountains in south-central France with a donkey named Modestine, describing the experience in his book 'Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes'.

After Fanny returned to the United States, Stevenson set sail for New York, leaving Greenock in August 1879. He didn't tell his parents and travelled against the advice of friends.

"Travel is of two kinds; and this voyage of mine across the ocean combined both … I was not only travelling out of my country in latitude and longitude, but out of myself."

Robert Louis Stevenson in 'Essays of Travel'

Stevenson and Fanny married in May 1880. A few months later they sailed back to Europe. They spent winters in the mountain towns of the Alps and summers in Scotland.

4. The novelist

Stevenson published accounts of the journeys he made throughout his life and used places he visited as settings for novels. When his body failed him and he was confined to bed, he travelled in his imagination.

"Sooner or later, somehow, anyhow, I was bound to write a novel… Men are born with various manias: from my earliest childhood it was mine to make a plaything of imaginary series of events."

Robert Louis Stevenson in 'My First Book: Treasure Island' in 'The Idler', August 1894

During the summer of 1881, Stevenson and his family stayed in a cottage in Braemar, Aberdeenshire. One afternoon he began drawing an elaborate map of an island. As he sketched imaginary woods, the "future character" of a book began to appear. It was 'Treasure Island', Stevenson's first novel. This tale of buccaneers and mutiny on the high seas remains his best-loved work. It has never been out of print.

In 1884, Stevenson's health declined sharply while he was staying in Europe, and his anxious parents persuaded him to return. Stevenson settled as far north as he dared, and his parents bought him a villa in Bournemouth, on the south coast of England. There he began work on 'Kidnapped', a story of the adventures of David Balfour following the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745.

Stevenson's work on 'Kidnapped' was interrupted by a dream, which was to become 'The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'. "Conceived, written, re-written, re-re-written, and printed in just ten weeks", Jekyll and Hyde became an immediate success. The names 'Jekyll' and 'Hyde' are now synonymous with good and evil.

"I dreamed the scene at the window, and a scene afterwards split in two, in which Hyde, pursued for some crime, took the powder and underwent the change in the presence of his pursuers."

Robert Louis Stevenson in 'Across the Plains'

5. The cat lover

In October 1885, while living in Bournemouth, Stevenson wrote to his friend, the poet WE Henley, "To Mr Henley ooralooralooralooraloo – The wife arrived with her pulse at 102. And a cat so lovely I don’t know what to do…"

The cat was 'Ginger', a semi-Persian Stevenson described as "not the genuine article". Fanny had bought Ginger for "ten bob" at a cat show at the Crystal Palace. Writing soon after to the novelist Henry James, Stevenson observed that Ginger "promises to be a monster of laziness and self-sufficiency".

Two years later, when the Stevensons left Bournemouth for America, Ginger needed a new home. Stevenson's friend Anne Jenkin stepped up. Stevenson thanked her "for the offer about Ginger, which we accept with exultation”, while Fanny wrote, "I do not know how to get him to you. Would it be safe, do you think, to put him in a cage and send him by parcel post?"

Fanny’s next letter begins, "have only a moment which I shall devote to explaining about Ginger. He will not eat unless his food is cut up very small indeed..." She continues in this vein for more than a page, worrying about Ginger's teeth, jaws, fur, weight and lungs.

6. The South Sea adventurer

In 1887, after the death of his father, Stevenson left for the United States once more, travelling with his family. The following year, in yet another attempt to find good health, he chartered a yacht and set sail for the South Seas.

Stevenson immediately took to life on board the ship. He slept on deck, which he describes as a "somewhat dangerous practice" and wrote that the time of his voyages had passed "like days in fairyland".

"I have watched the morning break in many quarters of the world; it has been certainly one of the chief joys of my existence, and the dawn that I saw with most emotion shone upon the bay of Anaho".

Robert Louis Stevenson in 'In the South Seas'

Though Stevenson set many of his stories in the South Seas, his native land remained in his thoughts and he completed the novel 'The Master of Ballantrae' during his cruise.

7. 'Tusitala' or the storyteller

Stevenson became increasingly fascinated by the Pacific islands and their peoples but his finances and his precarious state of health meant he couldn't travel indefinitely. After a visit to Samoa, Stevenson bought some land at Vailima on the island of Upolu.

He had a house built and seemed to enjoy his new role as head of the household at 'Villa Vailima'. He wrote to his friend RD Blackmore, author of 'Lorna Doone', "for the first time, I find myself a landholder and a farmer … the work seizes and enthralls me".

He began work on a new novel, the unfinished 'Weir of Hermiston', and developed an active interest in local politics. Stevenson wrote letters to 'The Times' highlighting the incompetence of the colonial administration.

The native Samoans quickly adopted this eccentric Scotsman, calling him 'Tusitala', which means 'storyteller'.

After Stevenson's sudden death from a brain haemorrhage on 3 December 1894, 40 Samoans cut a path through the bush to the ancient burial place of chiefs at the top of Mount Vaea. There, Stevenson's grave was dug and a makeshift tinsel cross was placed at its head.

The epitaph on Stevenson's tomb had been written by the novelist himself 14 years earlier, when he was ill in California.

"Under the wide and starry sky

Dig the grave and let me lie

Glad did I live and gladly die

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me

Here he lies where he longed to be

Home is the sailor, home from sea

And the hunter home from the hill."

Dive deeper

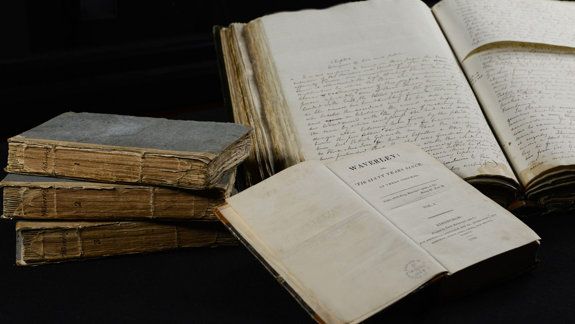

Browse early editions

Manuscripts and archives

Literature and poetry