Lord Byron's 'impossible' manuscript: 'Don Juan'

Introduction

On 16 July 1819, London publisher John Murray II wrote to his most famous author and friend Lord Byron from his house in Wimbledon. Writing the day after Murray had published the first instalment of Byron's satirical epic poem 'Don Juan', the publisher depicts Byron as a rising star.

"Though the most minute particle of the comets tale – yet I rise & fall with it, & my interest in your soaring above the other stars – & continuing to create wonder even in your aberrations is past calculation."

Letter from John Murray to Lord Byron, 1819 (Reference: MS.43496)

Murray's astral metaphor had been prompted by a recent sighting of a comet in the skies over Britain. In fact, one of Murray's marketing ploys for Byron's new book was to place adverts in London newspapers declaring 'Don Juan Tomorrow!', mimicking how news of the comet had been shared.

Who was Lord Byron?

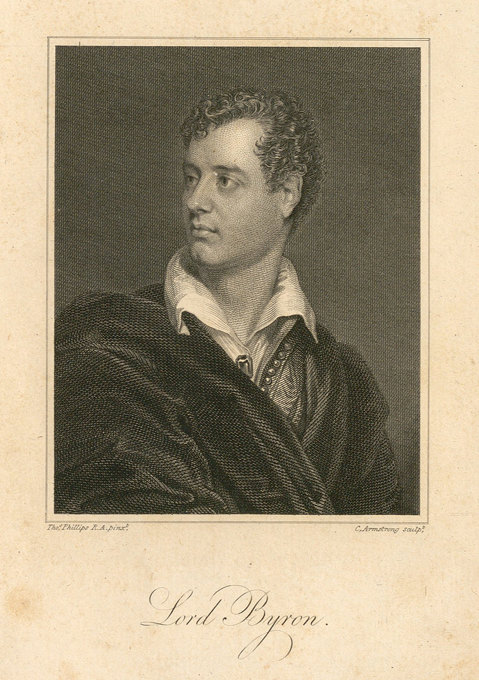

Lord Byron is often regarded as the first British celebrity. George Gordon Noel, sixth Baron Byron, was born in London in 1788 to an English father, Captain 'Mad Jack' Byron, and Scottish mother, Catherine Gordon. Young George went to Aberdeen Grammar School until he unexpectedly inherited the title Lord Byron at the age of 10. He moved to England and grew up to become a superstar of the Georgian literary world.

In 1812, his poem 'Childe Harold's Pilgrimage' was published by John Murray. Telling the tale of a world-weary young nobleman travelling through Europe, the poem was an overnight success. Byron himself wrote that he "awoke one morning and found myself famous".

For the next decade Murray published all Byron's works. In the process, publisher and author developed a friendship and their fortunes intertwined.

Mad, bad and dangerous to know

Fast, flashy, dazzling and fiery, Byron's rich descriptions, satire and playfulness provoked extreme reactions from readers and critics. As a dashing young aristocrat, Byron was in great demand at society parties.

Women clamoured to be introduced to the poet who they identified with the romantic hero of 'Childe Harold'. Lady Caroline Lamb, famously described Byron as "mad, bad and dangerous to know".

While Byron’s celebrity drove people to buy and talk about his writing, his extravagant lifestyle took a toll on his finances and his personal life. His ancestral home, Newstead Abbey, was put up for sale and his marriage to heiress Annabella Milbanke ended amid rumours of infidelity, madness, cruelty and sexual deviancy.

In 1816, Byron left his wife and young daughter Ada behind in London and travelled on the Continent. Settling in Italy, he continued to write instalments of 'Childe Harold' along with new poems and dramas.

While travelling, Byron sent letters to friends in England describing parties and the numerous women he fell in love with.

"It is the height of the Carnival and I am in the estrum & agonies of a new intrigue – with I don't exactly know whom or what – except that she is insatiate of love – & won't take money – & has light hair & blue eyes – which are not common here – & that I met her at the Masque – & that when her mask is off I am as wise as ever."

Letter from Lord Byron to John Murray, 27 January, 1818

In July 1818 Murray wrote to Byron asking for new work. Byron replied, "I have completed an ode on Venice; and have two stories,– one serious & one ludicrous". The 'ludicrous' one was 'Don Juan'.

Who was Don Juan?

Don Juan is a fictional character known for seducing women. A charismatic free-thinker from Seville, in most tellings of his story Don Juan kills the father of one of his lovers, but remains unrepentant.

The character first appeared in a tragic Spanish drama in 1630 and proved popular enough to feature in a number of different contexts after that, including a play by French writer Molière and an opera by Mozart, where he takes the Italian version of his name, 'Don Giovanni'.

In Byron's version, the narrator speaks directly to the audience and charts his own adventures. Readers are taken through love affairs, a shipwreck, a harem, a siege, the court of Catherine the Great and English society. The first part (or 'canto') of the poem describes Juan's love affair with the married Donna Julia. It ends with Juan being sent away on a sea voyage because of the ensuing scandal.

The impossibility of publishing 'Don Juan'

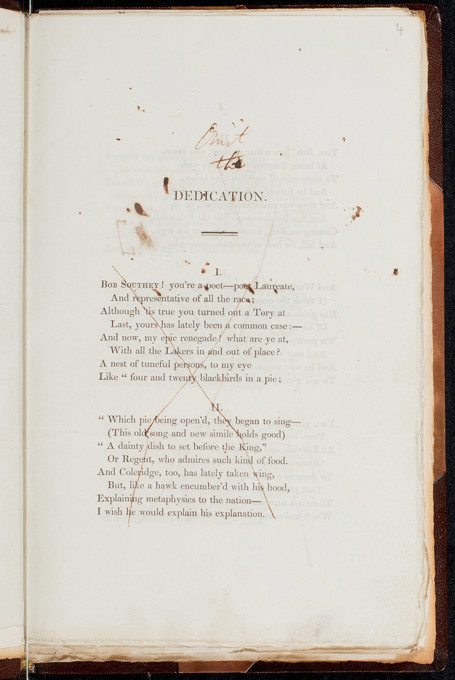

Given Byron's provocative nature, friends back in London felt nervous when they received the first canto of 'Don Juan' in December 1818. Though the poem was full of exotic locations, adventure, romance, wit and dazzling language – which the public would love – it laughed at religion and attacked fellow poets and public figures. What's more, unlike the traditional story, where Don Juan is a womaniser, Byron's innocent Juan is taught about love by the strong and passionate women he meets.

Byron's friends thought the poem wonderful, but worried about the indecent content and Byron's mockery of marriage. Byron's close friend John Cam Hobhouse wrote to Byron saying that, after consulting others, he felt 'Don Juan' was "impossible to publish".

Over the next few months, Hobhouse and Murray negotiated with Byron in an attempt to remove or alter passages they thought readers would find distasteful, controversial or lewd. A major concern was the character of Donna Inez. Although Byron denied any link, Inez was clearly based on his estranged wife Annabella. Attacks on public figures were to be expected from Byron, as was racy content. A cruel, mocking portrait of his wife, on the other hand, seemed a step too far.

Despite Hobhouse and Murray's efforts, Byron resisted making any changes. He wrote to Murray, "You shan't make canticles of my cantos. The poem will please if it is lively – if it is stupid it will fail – but I will have none of your damned cutting & slashing". Byron wanted his work to be judged on its literary merits. He told Murray he didn't care what the critics said, writing, "I will battle my way against them all – like a porcupine".

Though Byron liked to portray Murray as a stuffy conservative motivated by profit, perhaps the publisher had a better understanding of the public mood in England at the time. Against a background of economic depression, increasing social unrest and discontent about the Prince Regent's lavish lifestyle, Murray worried that Byron's anti-establishment views might not be received as the critique of British society their author intended.

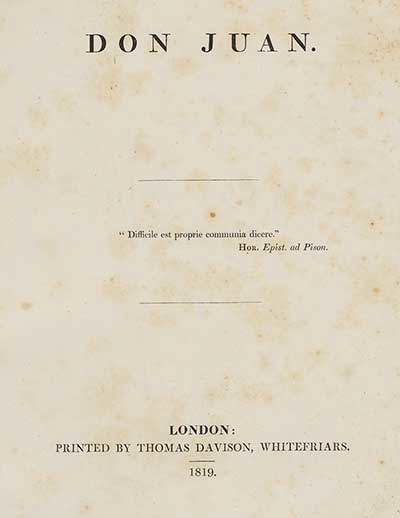

Finally, however, publisher and author reached a compromise. The solution? 'Don Juan' would be published with neither author nor publisher's name on the title page. While solving some of the pair's problems, this strategy later created others.

As 'Don Juan' progressed towards publication, Hobhouse continued to influence the final version of the work by adding comments to the proofs. Byron's friend felt that some topics, like cannibalism and syphilis, were unacceptable. He also worried about the personal attacks Byron had included.

At the beginning of the poem Byron had originally written a dedication in which he attacked the poet laureate Robert Southey. Byron disliked Southey's poetry and politics and was enraged when he heard that Southey had spread rumours about him. Once the decision to publish anonymously had been taken, though, he agreed to omit the dedication. Byron wrote on the proofs that he thought it unfair to "attack the dog in the dark".

When was 'Don Juan' published?

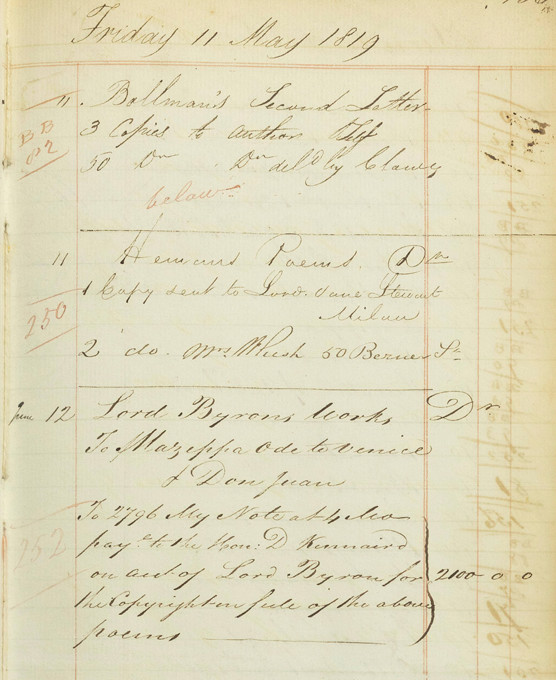

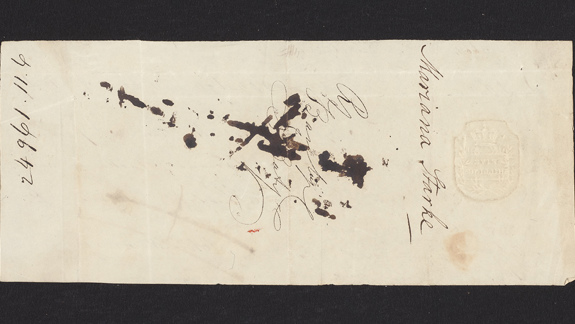

In May 1819, Murray purchased the rights to the first two cantos of 'Don Juan' and two other Byron works for £2,100. The first edition of the first two cantos were published on 15 July the same year, in a large expensive volume priced at £1 15s 6d. 1500 copies were produced, followed up by a smaller cheaper version costing 9s 6d.

Both Byron and his publisher anticipated that 'Don Juan' would create a sensation. However, neither had any idea whether the work would position Byron as a great poet of the age or, just as likely, lead to his downfall. In his letter to Byron the day after publication Murray wrote from his house at Wimbledon, "Having fired the bomb – here I am out of the way of the explosion".

"Its publication has excited a very very great degree of interest – public expectation having risen up like the surrounding boats on the Thames when a first rate is truck from its stocks. As yet my scouts & dispatches afford little clue to public opinion".

Letter from John Murray to Lord Byron, 16 July 1819 (Reference: MS.43496)

Scathing reviews

When the reviews arrived, critics writing in respectable middle-class publications such as 'Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine' were scathing. In a three-page article the magazine denounced 'Don Juan' as "filthy and impious". Perhaps more damaging were accusations that Byron had turned on readers by mocking their values.

"Love–honour–patriotism–religion, are mentioned only to be scoffed at and derided, as if their sole resting-place were or ought to be, in the bosoms of fools".

Extract from review of 'Don Juan', 'Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine', August 1819 (Shelfmark: NJ.322)

Even readers who fell for Byron's charms questioned his decisions. Hariette Wilson, a famous courtesan who had affairs with a number of well-known politicians, wrote to Byron from Paris with her thoughts on the poem. She began flirtatiously saying she "took [Don Juan] to bed with me, where I contrived to keep my large quiet good looking brown eyes open". Wilson then scolded Byron for parodying the Ten Commandments.

"Dear adorable Lord Byron don't make a mere course old libertine of yourself… What harm did the Commandments (no matter by whom composed, whether God or mortal) ever do to you or anybody else? & what catch penny ballad writer could not make a parody on them?"

Hariette Wilson writing to Lord Byron in July 1819 (Reference: MS.43512)

A book ripe for piracy

The scandal surrounding 'Don Juan' may have boosted its sales, but its anonymous publication left the field open for others to produce pirate copies. Because the publisher's name didn't appear in the book, Murray had limited legal recourse to challenge the unauthorised versions that soon appeared.

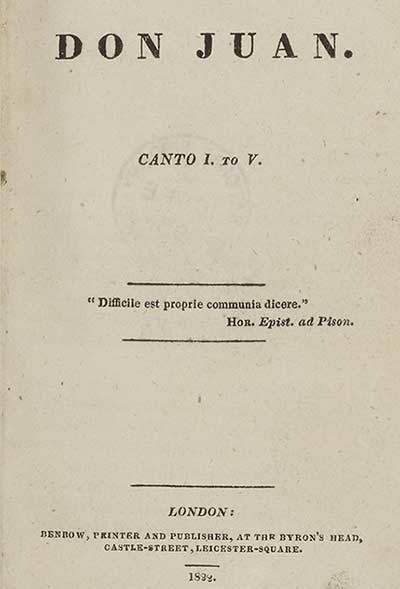

One London publisher, William Benbow, sold his 'Don Juan' at a much lower price. His 1822 edition of cantos I-V cost just two shillings. Benbow even named his bookshop 'The Byron's Head'. Therefore, for the first time, Byron's name appeared on the title page of his poem.

Poet Robert Southey described Benbow's shop as "one of those preparatory schools for the brothel and the gallows, where obscenity, sedition, and blasphemy, are retailed in drams for the vulgar". Associations with Benbow therefore did little for Byron's reputation.

Throughout the 1820s, the relationship between publisher and poet became increasingly strained. In 1822, after cantos I-V of Don Juan had appeared in print, Byron broke with Murray, and subsequent cantos were published by the radical publisher John Hunt.

Two years later, Byron died in Greece, where he had gone to support the struggle for Greek independence. After his death, Murray purchased the rights to all 16 cantos of 'Don Juan'. Though the poem remained unfinished, later editions restored the dedication to Robert Southey and printed the text as Byron had intended. Many scholars consider Byron's "impossible" work to be one of the greatest long poems in the English language.

About the author

Kirsty McHugh is the Curator, John Murray Archive & Publishers' Collections at the Library. Kirsty's research interests are in social and cultural history, in particular travel writing, manuscript and print culture, reading and publishing history.

Dive deeper

'Don Juan' manuscript

The John Murray Archive: Pioneering British publishing

Printing and publishing