James VI and the Union of the Crowns

Introduction

James VI in Scotland

James Stuart came to the Scottish throne in 1567. Crowned King of Scotland when just one year old, James replaced his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, who had been forced to abdicate.

Scotland was then a fragile country, harbouring painful memories of wars with England. Internally, nation and Church faced threats from local chiefs and warlords, who ruled the borders and islands. While Roman Catholics opposed the ongoing Reformation, the Protestant church was divided over structure and doctrine.

In these turbulent times, James was seen as an important symbol of the Scottish nation. Unlike his mother, he was a Protestant and therefore reinforced the authority of the reformed Church of Scotland, known as the Kirk.

As James grew up and took on the responsibilities of ruling Scotland, he gradually managed to bring a greater degree of order to the main areas under his authority. Classically educated, he also sparked a cultural revival.

James loved writing poems. Aged just 19, he had written a book in Scots called 'The essayes of a prentise, in the diuine art of poesie...' that set out the principles of Scottish poetry. His patronage attracted a thriving group of poets, dramatists, artists and craftspeople to the royal court.

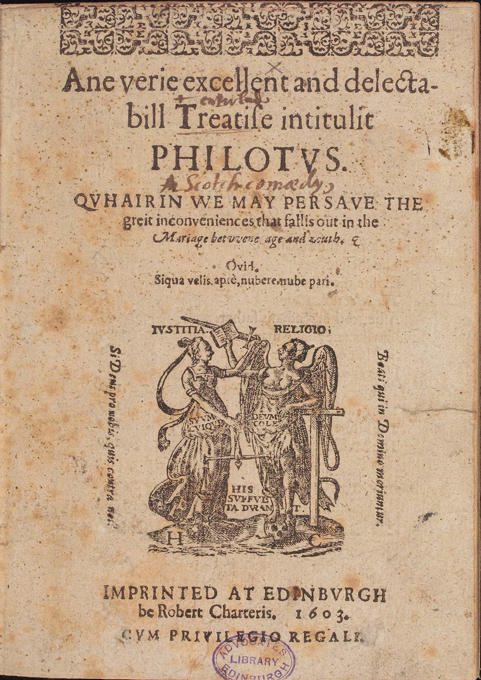

One of the few surviving early Scottish plays, the bawdy comedy 'Philotus', from 1603. [Shelfmark: H.29.c.33]

Having fathered two male heirs by the end of 1600, James had already ensured a stable line of succession.

How did James VI become king of England?

England, on the other hand, was ruled by a queen who had no children. This was a problem for a country larger and richer than Scotland, with a longer tradition of strong central government.

Though Queen Elizabeth I had always refused to discuss the matter of who would take over from her, most people knew that James was the only suitable candidate. Like Elizabeth, he was a Protestant. Plus, he had been a successful king for many years and had healthy children who could take over on his own death.

On the other hand, James came from a different country and spoke a different language. At the time, Scots was the norm in Scottish government and law, literature and officialdom, as well as the everyday language of kings, scholars, courtiers and commoners. Worse, James's home country had a history of conflict with England and the former Queen Elizabeth I had had his mother executed for treason.

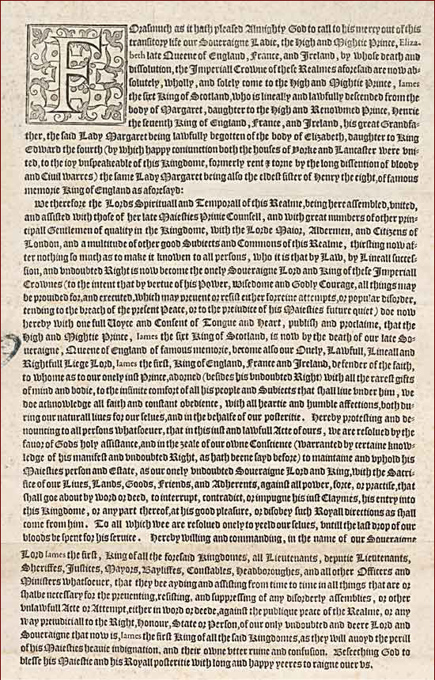

Despite all this, James won the backing of the English establishment, and lengthy family trees were compiled that showed how he was related to the English houses of York and Lancaster. When Elizabeth died in 1603, the Scottish king was proclaimed King James I of England.

Welcoming the new king

News of the new king was quick to travel north. James, who had always hoped to hold the English throne, packed his bags and left Edinburgh for London. The English capital was considered the only place to be for the new ruler of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales.

James told the distressed citizens of Edinburgh that he would return frequently, but it must have been obvious that Scotland was going to lose out. The court, including the leading Scottish poets, moved south and James only returned to his home country once, over a decade later.

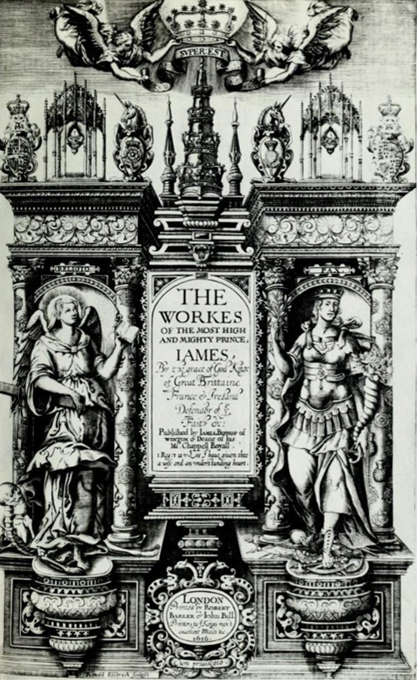

James VI and I, from his collected 'Workes', 1616. [Shelfmark: Nha.M45]

As James travelled south, he gave out honours and money in an effort to win admiration from his new subjects. His writings were also republished in England. The English were understandably nervous about James's plans for their country and they worried about Scots seeking positions in London. But, relieved to have a ruler again, English aristocrats hurried to acclaim their new master.

What was James VI known for?

James VI was a learned monarch. He spoke several languages, gave eloquent speeches and wrote about theology and politics.

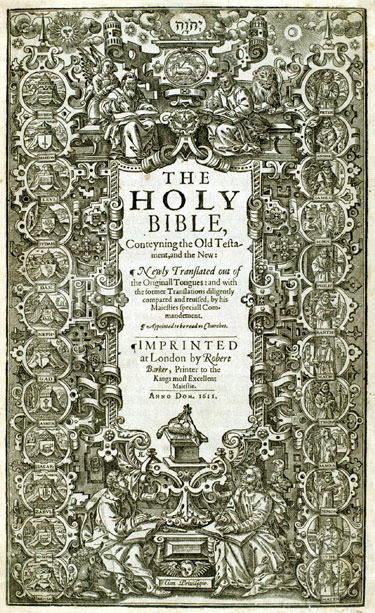

Within days of arriving in London, the new king gave a royal patent to a theatrical group co-owned by William Shakespeare. A year later he commissioned a new version of the Bible. Initially, 'The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament, and the New' attracted little interest, but for a time it grew to become the most popular translation of the Bible in English. Today, it's known as the 'King James Bible'.

Title page from The Holy Bible commissioned by King James, printed in London in 1611. [Shelfmark: H.S.385]

Rather less positively, some historians accuse James of being a self-indulgent character, over-fond of drink and dependent on young male favourites.

Politically speaking, however, James governed Scotland with great success and worked for religious peace in Europe. Keen to establish a united and peaceful British nation, he is known for bringing Scotland and England together in the 'Union of the Crowns'.

What is the Union of the Crowns?

James began his English reign with all kinds of hopes and ambitions. One of his first projects was a plan to create a full legal and political union of England and Scotland. He called himself "King of Great Britain" and, in 1607, told the English Parliament about his desire for "a perfect union of laws and persons, and such a naturalising as may make one body of both kingdoms under me your King".

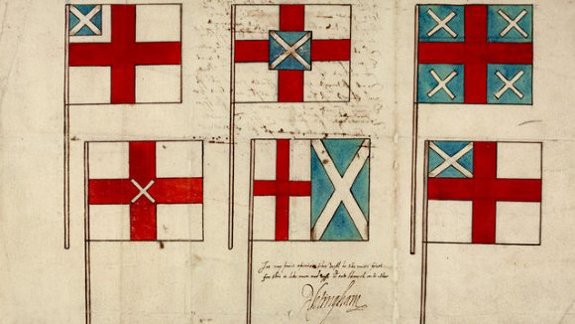

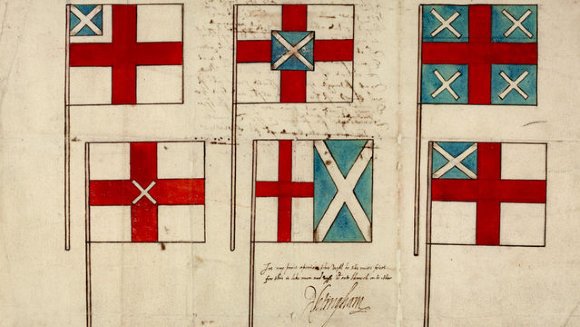

James issued a new gold coin bearing a Latin inscription that translates as, "I will make them one nation" written in Latin and even commissioned designs for a new flag. Each flag combined the English emblem of St George’s Cross with the Scottish saltire of St Andrew.

Six designs that brought the St George Cross of England together with St Andrew's Saltire of Scotland in a proposed Union flag. [Reference: MS.2517]

As part of James's plan, Scotland would no longer be a separate country. Instead, it would be treated like an English shire, similar to a region like Northumberland. While the Scots weren't keen on this outcome, the English were also suspicious. They worried the union would threaten their identity.

To James's dismay, the English Parliament threw his plans out. The only union they allowed was a union of crowns. This linked two distinct countries together because they shared the same king, but retained two separate parliaments.

A struggling reformer

Many of James's other ideas went the same way as his attempt to unite England and Scotland. When he encouraged England to make peace with traditional Catholic enemies, like Spain, he was accused of giving in to 'popery'. His plan for 'civilising' Ireland by settling thousands of Protestant Scots in Ulster also generated conflict. And his attempts to make the Scottish Kirk more like the Church of England proved unpopular.

The King's English subjects were bemused when he spent much of his time hunting, watching theatrical performances and conducting theological disputes with the Pope. He never visited Ireland, Wales or the Highlands and islands of Scotland. His hopes for a culturally united 'British Isles' never came to fruition. Even James's previous success in sparking a renaissance of Scots literature was soon snuffed out. When the royal court moved to London, many court poets began writing in English instead of their native Scots.

Today, many of James's opinions seem shocking or bizarre. For instance, he approved the burning of heretics, asserted that only God had authority over him and ordered that the lower classes should not be allowed to play bowls.

Title page from James's collected 'Workes', which discussed theology, politics, witchcraft and smoking. [Shelfmark: Nha.M45]

However, in other areas, James seems to have been ahead of his time. He warned against the dangers of passive smoking, called for the protection of forests and cultivated friendships with supposed enemies.

Other notable historical events from his reign include the formation of Jamestown in North America in 1607 and the Pilgrim Fathers arriving in Plymouth in 1620. The latter established the first permanent English-speaking community in New England in what was then the New World.

How did the Union of the Crowns affect England and Scotland?

When James decamped to London, Scotland was managed by strong nobles and officials, who received frequent messages from their distant king. Scotland remained generally peaceful and maintained its separate system of law and government. Edinburgh's status as a capital city was, however, diminished and Scotland never had another monarch who spoke the Scots language.

Title page of 'The Miraculous and Happie Union' (1604), one of the many books produced in support of the Union of the Crowns. [Shelfmark: L.C.696(1)]

If James had not become King of England, it seems highly likely that England and Scotland would have continued to develop into two separate modern nation-states. Indeed, after his death in 1625, the union of the crowns began to fall apart. James's union had, after all, given England a royal family it distrusted, while leaving Scotland without its key symbol of national independence. The civil wars that began in 1642 were, in part, sparked by the removal of the Scottish king from his country.

By the end of the 1600s, though, the House of Stuart had been expelled from Britain and there was new talk of a union. After much negotiation between the two countries, and against the wishes of James's exiled descendants, England and Scotland were united into one kingdom in 1707. Both Scottish and English Parliaments dissolved, to be replaced by a Parliament of Great Britain. No longer citizens of an independent nation, Scots had to adopt English currency. While some Scottish merchants faced new competition from England, others benefitted by gaining access to trade with the English colonies.

The union today

Four hundred years after the Union of the Crowns, devolution reversed some of the effects of 1707. Scotland and England still share a monarch but, in 1999, Scotland once again established its own Parliament.

If James were to return to Edinburgh in the 21st century, there's much he would recognise. Parts of the skyline remain, and aspects of culture and politics. As it was during his own Union of the Crowns, Scotland retains many of the qualities of nationhood, without holding full independence.

Dive deeper

James VI and I: A life and reign in 10 parties

Scottish history