The last letter of Mary, Queen of Scots

Introduction

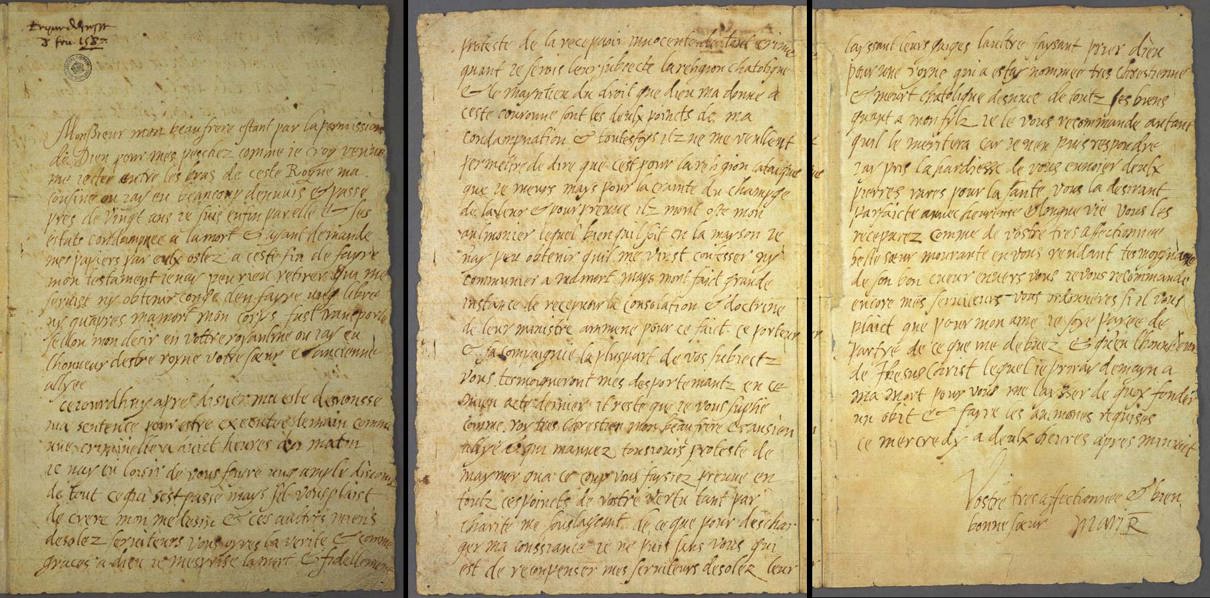

At 2am on Wednesday 8 February 1587, Mary, Queen of Scots wrote her last ever letter. Addressing her brother-in-law, King Henri III of France, she told him, "I am to be executed like a criminal at eight in the morning".

Mary wrote the letter at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire, where she had been put on trial for treason a few months before.

Who was Mary, Queen of Scots?

Mary was born in Linlithgow Palace on 8 December 1542. When her father James V died six days later, Mary became Queen of Scots. Given her age, the country was ruled by regents until Mary reached 18. One of these regents was Mary's mother, Marie de Guise, who ruled in Mary's name from 1554 to 1560.

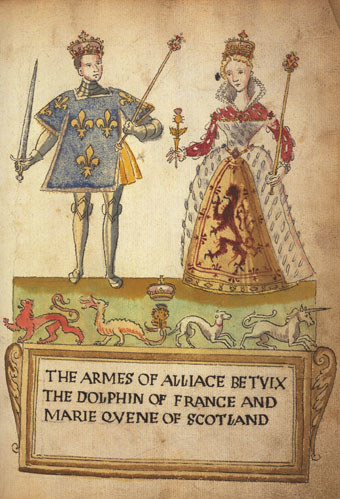

When she was five years old, Mary was sent to the French court, where she received a French education. Ten years later she married Francis, who would soon become King of France. Within three years, Francis had died and Mary, who was just old enough to become queen, returned to Scotland.

Mary reigned as Queen of Scots from 1561 to 1567. A Catholic queen at a time when Protestants were calling for reform, Mary delivered stable policy and government until involvements with Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley and the Earl of Bothwell created problems.

After a rebellion of Scottish lords, Mary was imprisoned and forced to abdicate and fled to England. After crossing the border in May 1568, she was immediately held at Carlisle Castle, by order of the English Queen, Elizabeth I.

How was Mary, Queen of Scots related to Elizabeth I?

Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I were first cousins once removed. Mary's grandmother, Margaret Tudor and Elizabeth's father, King Henry VIII, were brother and sister.

Both Mary and Elizabeth were descended from Henry VII, so both had a claim to the English throne. In fact, in the eyes of Catholics throughout Europe, Mary had a stronger claim than her Protestant cousin Elizabeth, who they considered illegitimate.

Elizabeth's dilemma

When Mary fled to England, Elizabeth was faced with a dilemma. Instinctively she wanted to protect her cousin. On the other hand, if Elizabeth wanted to maintain her own position as head of the English state, she couldn't risk setting Mary free.

Initially, Elizabeth kept Mary as a 'guest', but after a hearing in Westminster Mary was jailed. She spent the following 18 years in captivity. During this time Mary was moved to a number of different castles or manor houses.

Why was Mary, Queen of Scots executed?

Throughout her time in England, Mary symbolised the hopes of English Catholics who saw an opportunity to restore their country to Catholicism. Catholic Kings in France and Spain also wanted Mary on the English throne, since they believed this would give them more power and influence in England.

Whether directly or indirectly, the imprisoned Mary became involved in English plans for Catholic uprisings and diplomatic intrigues on the continent. Some of these brought threats of foreign invasion.

Mary's fate was eventually sealed when she was implicated in the Babington Plot, a scheme to overthrow Elizabeth and place Mary on the English throne. Mary's involvement was revealed by Elizabeth's spymaster Francis Walsingham, who intercepted Mary's letters to the plotters. When Mary wrote that she approved of their scheme, Walsingham had all the evidence he needed.

Though Elizabeth was reluctant to execute another anointed monarch, her ministers cajoled her into signing her cousin's death warrant.

What does Mary, Queen of Scots' last letter say?

Writing in French, Mary explains her situation in brief. Having thrown herself "into the power of the Queen my cousin", she writes, "I have finally been condemned to death by her and her Estates".

Mary complains that she's unable to make a will because her papers have been taken away. She wishes she could plan for her burial, which she wants to take place in France, and says she isn't allowed to see her chaplain either. This means she can't make a final confession of her sins or receive the last rites, both important actions for a Catholic to complete before they die.

Though the English government insisted that Mary's death sentence was a purely political matter, Mary says in her letter that she's dying a religious martyr, executed for her loyalty to her Catholic faith. Combined with her claim to the English throne, Mary knows her religion posed a considerable threat to Elizabeth.

"The Catholic faith and the assertion of my God-given right to the English crown are the two issues on which I am condemned, and yet I am not allowed to say that it is for the Catholic religion that I die".

Extract from the last letter of Mary, Queen of Scots, 1587

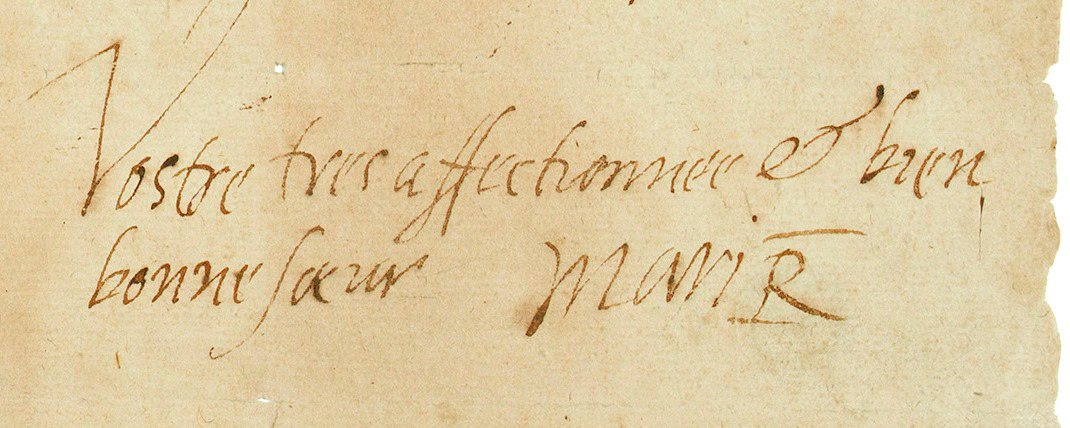

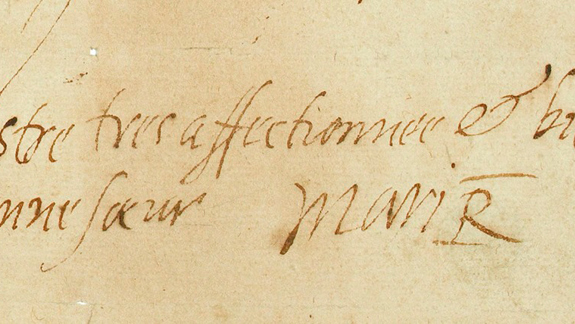

Towards the end of the letter, Mary beseeches King Henri to have "prayers offered to God for a queen who has borne the title Most Christian, and who dies a Catholic, stripped of all her possessions". She asks her brother-in-law to pay her servants the wages due to them and to organise a mass for her. She then signs off with, "your very loving and most true sister, Mary R".

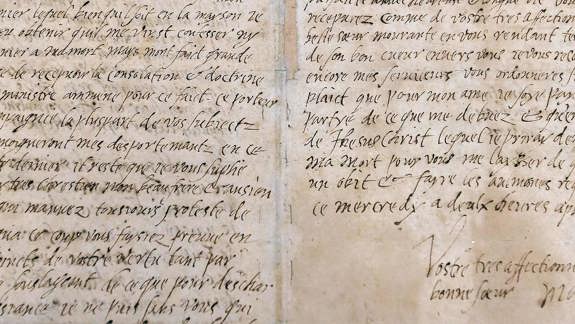

Once the ink on the letter was dry, the manuscript sheets were folded into a secure packet so no-one could tamper with its contents without leaving a trace. Just a few hours later, on 8 February 1587, Mary was executed in the Grand Hall at Fotheringhay Castle. Aged 44, she had spent almost half her life under lock and key.

How did Mary's letter end up at the National Library of Scotland?

Mary's doctor Dominique Bourgoing took the letter to France, though not immediately. Bourgoing made a report to Henri III later that year and presumably delivered the letter then. It was, however, left to Philip II of Spain to authorise wages and pension payments to Mary's servants.

The letter remained in the French royal archives until, at some unknown date, it was given to the Scots College in Paris, a Catholic seminary for Scottish priests. It remained there until the French Revolution, when the College was dissolved and its archives dispersed. Passing through the hands of various owners, the letter eventually became part of a collection of autographs owned by English collector Alfred Morrison.

In 1917 a number of men clubbed together to purchase the letter from Morrison's widow. Five years later they presented it to the Scottish nation through the National Art Collections Fund. The letter was held by the Advocates Library until 1925, when the National Library of Scotland was created. It is still held in the Library today.

Written by one of Scotland's most famous and controversial figures, the letter documents a significant event in Scottish history – the execution of a Scottish monarch by the English crown. More poignantly, it provides some insight into how Mary felt on that winter's day over 400 years ago, when she had just a few hours left to live.

Dive deeper

Mary Queen of Scots catalogue entry

Mary Queen of Scots' last letter transcription