The plague in Scotland

Introduction

When did the plague reach Scotland?

Plague epidemics ravaged Europe from the 6th to the 17th centuries. The first known outbreak in Scotland occurred in 669. It appears to have been contained to the Lothians around Edinburgh. The first epidemic-level outbreaks in Scotland were recorded in 1349 to 1350 and again in 1362.

"In the year 1349 there broke out a universal pestilence …, which lasted a great many years in Scotland. Nearly a third of the population perished in it. It attacked the common people chiefly, not the great."

From 'Liber Pluscardensis'

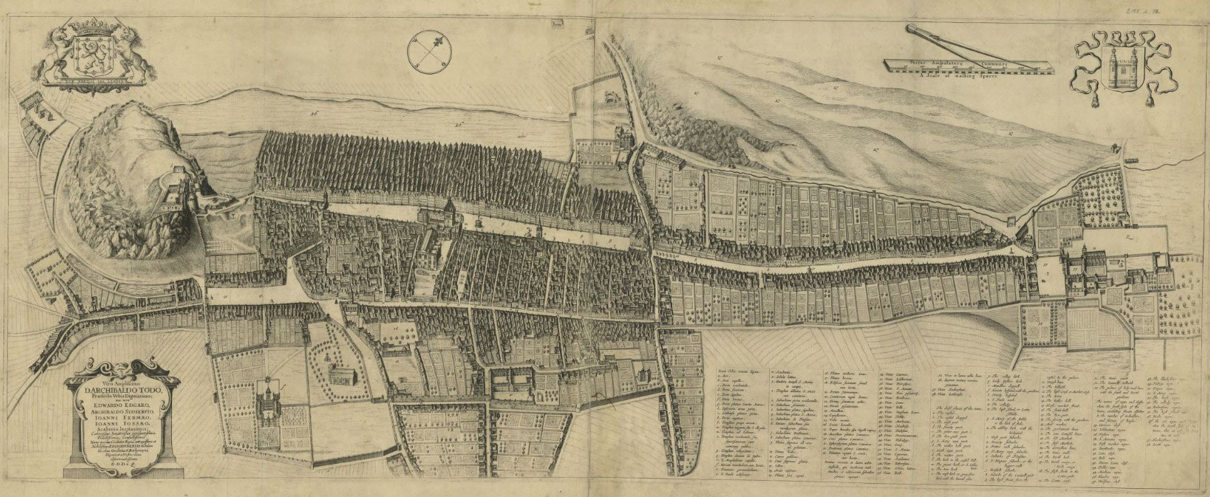

While the 1400s saw just two major outbreaks, Scotland suffered from serious plague outbreaks during the whole of the 1500s. The disease mostly affected the Central Belt, but also Dumfries, Fife, St Andrews, Dundee, Aberdeen and Elgin. In 1645, cramped living conditions in Edinburgh contributed to the rapid spread of the disease. Epidemics and more contained incidents in Scotland went on at short intervals until the mid-1600s.

There are few references to the plague in the Highlands and Islands. However, we know folk medicine remedies against the plague existed in these sparsely inhabited areas, which suggests they also experienced outbreaks.

Measures against the plague

Centuries later, writer Robert Louis Stevenson wrote in his 1879 guidebook 'Edinburgh: Picturesque notes' that during times of plague, "'stamping out contagion' was carried on with deadly rigour". Stevenson describes how officials in grey gowns with white St Andrews crosses on their backs walked the city's streets, punishing anyone who concealed their plague symptoms. Women were drowned in quarry pits and men were hung and gibbeted in their own doorways.

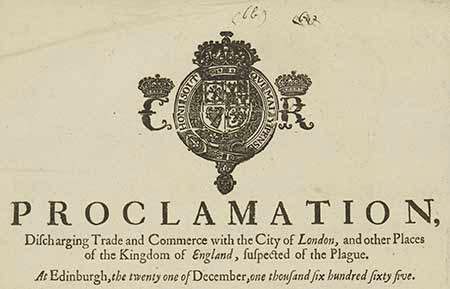

However, the Great Plague of 1665 to 1667 never reached Scotland. This was largely thanks to preventive measures. The Scottish government passed acts that forbade trade with countries affected by the plague, like England and the Netherlands.

Even after epidemics subsided in these countries, further acts imposed a forty-day quarantine on goods imported from them. Though preventing the import of plague, this interruption to trade was very disruptive, not least because England and the Netherlands were two of Scotland's main trading partners.

How plague outbreaks impacted Scottish people

The impact of plague outbreaks on society was devastating. Apart from the high number of deaths, plague affected the lives of craftspeople, small merchants and labourers far more than the well-off. The latter often took the opportunity to leave crowded towns where contagion was high. Escaping to their country estates, they had the means to wait out the end of an outbreak.

People remaining in towns weren't so lucky. They risked contracting plague while keeping society functioning with a weakened workforce. Once an outbreak was over, wages for the diminished working population rose exponentially. However, food and other provisions became more expensive, since fewer people were working the land.

Cures for the plague

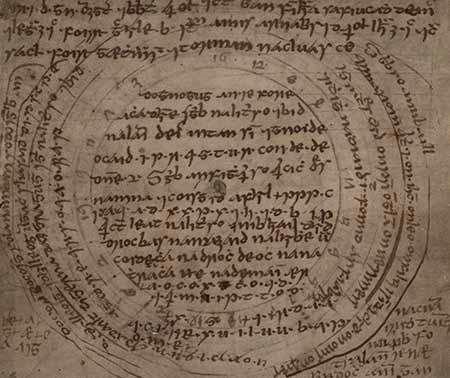

The National Library of Scotland holds two examples of Scottish healers' efforts to protect against the plague. The first is a hand-written wheel charm from the 1500s. Assembled by the Beatons of Mull, a family of hereditary Gaelic healers to the Scottish kings, the charm was intended to protect against violent death, poison and demons of the air, which were thought to spread the plague.

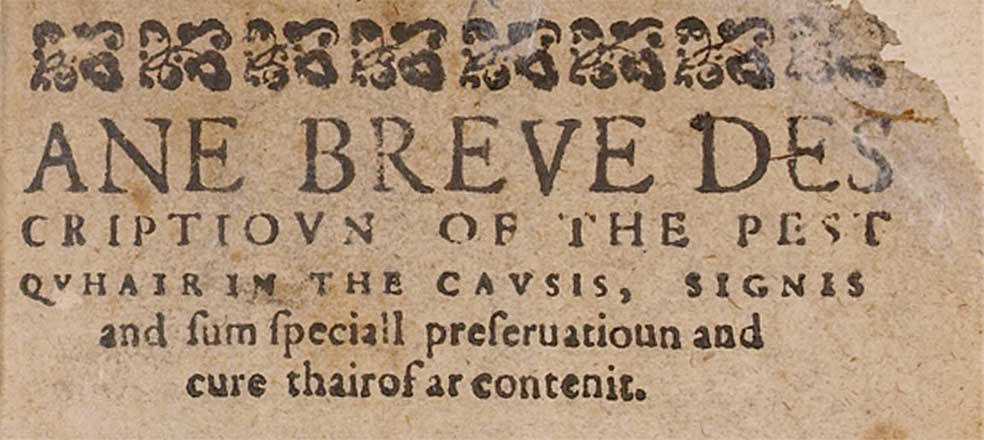

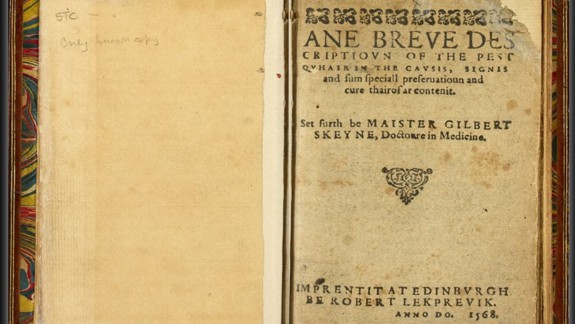

In 1568, a Scottish doctor published a book inspired by the plague outbreak of 1564 to 1569. Discussing the recognition, treatment and prevention of the plague, 'Ane Breve Descriptiovn of the Pest' is Scotland's first printed medical text. It was written in Scots so common people could read the book themselves or understand if it were read to them.

Author Gilbert Skeyne was Professor of Medicine at King's College, Aberdeen. He later became personal doctor to the King of Scotland James VI. His text was part of a European-wide phenomenon of plague publications. These were often penned by doctors who fled infected towns. In Skeyne's case, he lived and worked in Aberdeen, but with the city lacking a printing press, his book was printed and distributed in Edinburgh, a city ravaged by the plague when the book published. It's estimated that the 1564 to 1569 outbreak killed about a fifth of the Edinburgh's inhabitants.

Skeyne listed numerous causes of the plague, including stagnant water, filth, unburied carrion, decayed plants and food, and noxious "infected air". He and others suggested cures like ointments, plasters and mixtures derived from plant and vegetable sources. Ultimately, Skeyn suggests the principal preservative against the pestilence is "to returne to God".

These views are typical of the period. They lacked originality and shed no new light on the subject. Indeed, many of Skeyne's comments can be identified in earlier Latin and English works, some dating as far back as the writings of 2nd-century Greek physician Galen of Pergamon. Skeyne would have been aware of texts like this because students studying medicine on the Continent brought them back to Scotland.

Sadly, there was nothing new to be said about the plague at the time. Its cause remained unknown until the end of the 19th century, and there was no effective treatment before then.

"To preserve from the Infection of the Plague: Take Garlicke peal it and mince it small, put it into new milke and eate it fasting."

From 'Present remedies against the plague, 1603'

What caused the plague?

Until the end of the 19th century, doctors and common people alike were completely in the dark about what caused plague. For centuries, it was viewed as God's judgement on the sins of the people. Calls to repent and make changes to your life were therefore heard across the country. When it came to the physical mechanism of contagion, many people blamed 'bad miasma' (contaminated air).

As a precaution against infection, plague doctors covered themselves in leather coats. They wore gloves and placed juniper in their masks to fight against the bad air. Some plague doctors did indeed survive, but not because they fended off infection in the air. Rather, their clothing prevented rat fleas from biting them. They didn't know it then, but plague was carried by these fleas.

The real cause of the bubonic plague was only understood when French doctor Alexandre Yersin and Japanese bacteriologist Kitasato Shibasaburo independently discovered the bacteria responsible in 1894 in Hong Kong. Both scientists were shown local facilities for patient care and diagnosis by a Scottish doctor, James Lowson, who was acting Superintendent of the Civil Hospital in Hong Kong at the time.

We now know that the plague bacteria (known as 'Yersinia pestis') is carried by rodent fleas. The fleas become infected when they bite infected rats. If an infected flea then bites a human, it regurgitates blood carrying bacteria into the wound. From there the bacteria make their way through the human lymphatic system.

Scotland's last outbreak

Plague outbreaks have been contained since the discovery of antibiotics, but they haven't been eradicated. The last plague outbreak in Scotland occurred in Glasgow in August and September 1900. It is thought the disease entered the city by rats arriving via international shipping routes. A total of 36 people became infected and 16 died. The number might have been lower if the disease had been recognised more quickly.

Dive deeper

Read 'Ane Breve Description'

Lifting the lid

Word on the Street