The Power of the Powerless at Greenham Common: Beth Junor’s archive of peace and protest

Introduction

Beth Junor has been dedicating herself to peace and justice activism for more than four decades. Combining her writing with her campaigning, she uses anything from poetry to pamphlets to advocate for non-violence, disarmament and human rights. Through her participation in Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp in the 1980s and '0s, and long-term involvement with various social justice organisations, Junor believes "when faced with any injustice, the human spirit will win out in the end".

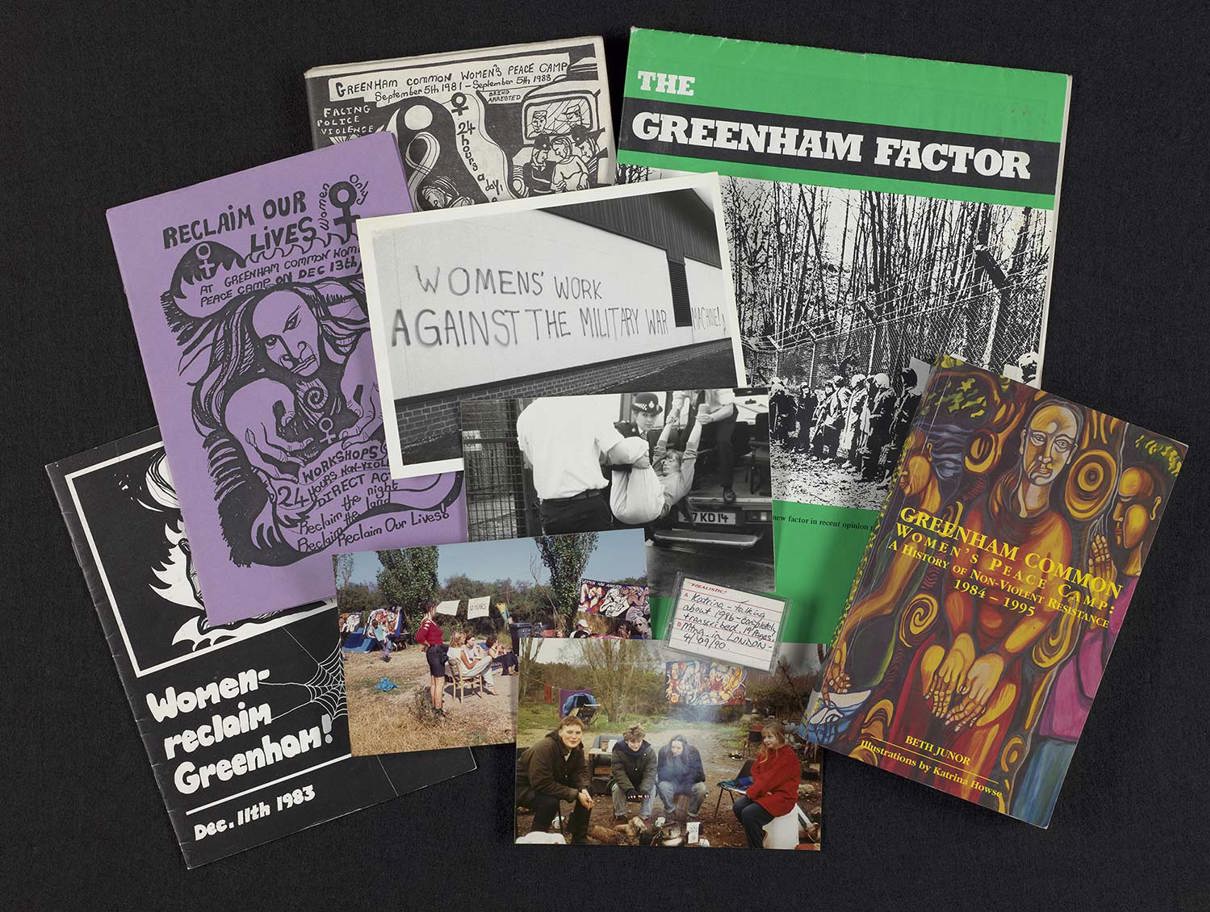

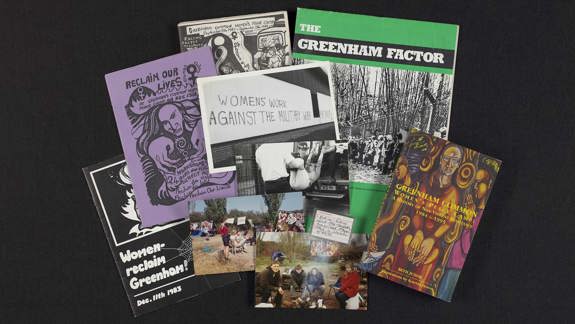

Born in Lanark, one of Junor's earliest memories is of running around her local library. "This is such a good memory," she says. "I look on it now as a library being a place of exploration and safety, and I have loved being in libraries all my life." It is fitting then that Junor's archive is now housed and made public by the National Library. The archive, consisting of 23 boxes, contains material related to Junor's anti-nuclear and peace activism, her poetry and writing, as well as her work with various social justice organisations including Scottish PEN. The entirety of Junor's archive, which includes manuscripts, correspondence, research papers and photographs, is available to consult in our Special Collections Reading Room.

At the heart of the archive is a series of material related to Junor's involvement with Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp. She became involved in anti-nuclear campaigning while studying at St Andrews University. "It's hard to describe the atmosphere in the country at that time," she says. "The Cold War was on everyone's mind, nuclear weapons were in the news constantly. People were having nightmares about nuclear war and there was an atmosphere of fear."

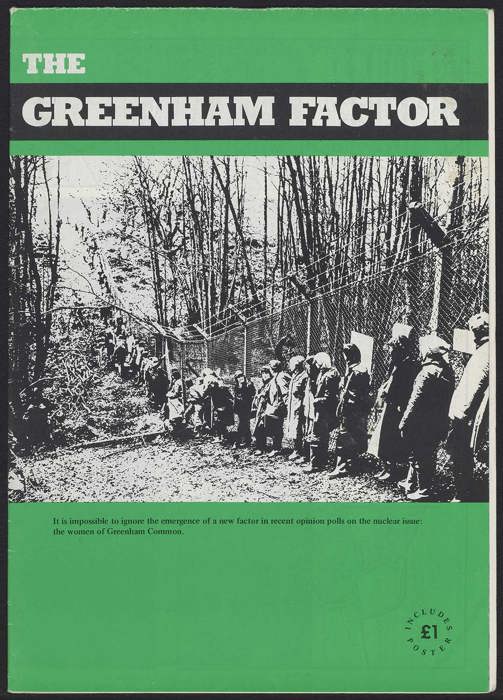

The peace camp, active from 1981–2000, saw tens of thousands of women come together outside the gates of RAF Greenham Common military base in Berkshire, England, to protest the stationing of American cruise missiles on the land. It remains one of the largest feminist protests in history. "They were being watched," says Junor. "And we were focused women from all over the earth."

Junor first visited Greenham in 1983 and remained involved with the camp after moving to Aberdeen, where she began her career as a speech and language therapist. "I happened to be at the camp when the Chernobyl explosion happened," she recalls. "It was said that the winds from Chernobyl were coming over. I had waterproofs, which I took to the University of Aberdeen on my return. They scanned the seams with the Geiger counter and when it went over the seams the Geiger counter went berserk."

It was after this experience, in 1986, that Junor made the life-changing decision to live full-time at Yellow Gate, the camp outside the main gate to the military base. She remembers thinking, "if I do grow to be older and I look back on my life and find that there is something I regret not doing, what would it be? And I decided to go and live at the women's peace camp". She lived there for three and a half years, describing the experience as "the most marvellous education".

"I was worried about it," she admits. "I felt 'who am I to take this on?' But I felt 'if I can do it, then others can do this as well'. I'd grown up in cultures at home of always being aware of the news and just a basic sense of decency and fairness and justice […] I think that is partly what gave me the determination and the strength." She adds "it's also the privilege I had as a white woman. I was able to engage in this and then, later, go back to my career. I am aware that there was a privilege of choice within that. But it was a necessity for me. I can't imagine now having done things differently."

When Junor arrived, there had already been large-scale evictions at the camp, with police removing the women's semi-permanent shelters (called 'benders'), so they were living outdoors in temporary tents. "The fire was the centre of the camp," Junor recalls. "We knew that as long as we could keep the fire going, we would hang on, we would hold on to that land. And that was the aim, to keep the presence, to bear witness to the exercises of the cruise missile convoy."

Day-to-day, the women's main tasks were collecting firewood and water. "It was a very primitive way to live," she says. "Hard, but sustainable through the support of each other and the support of the land." The photographs in Junor's archive provide a glimpse into these experiences, recording the daily realities of camp life, such as living under canvas, cooking on an open fire and welcoming visitors. Junor describes living at the camp as a "spiritual resistance" to the preparation of nuclear weapons.

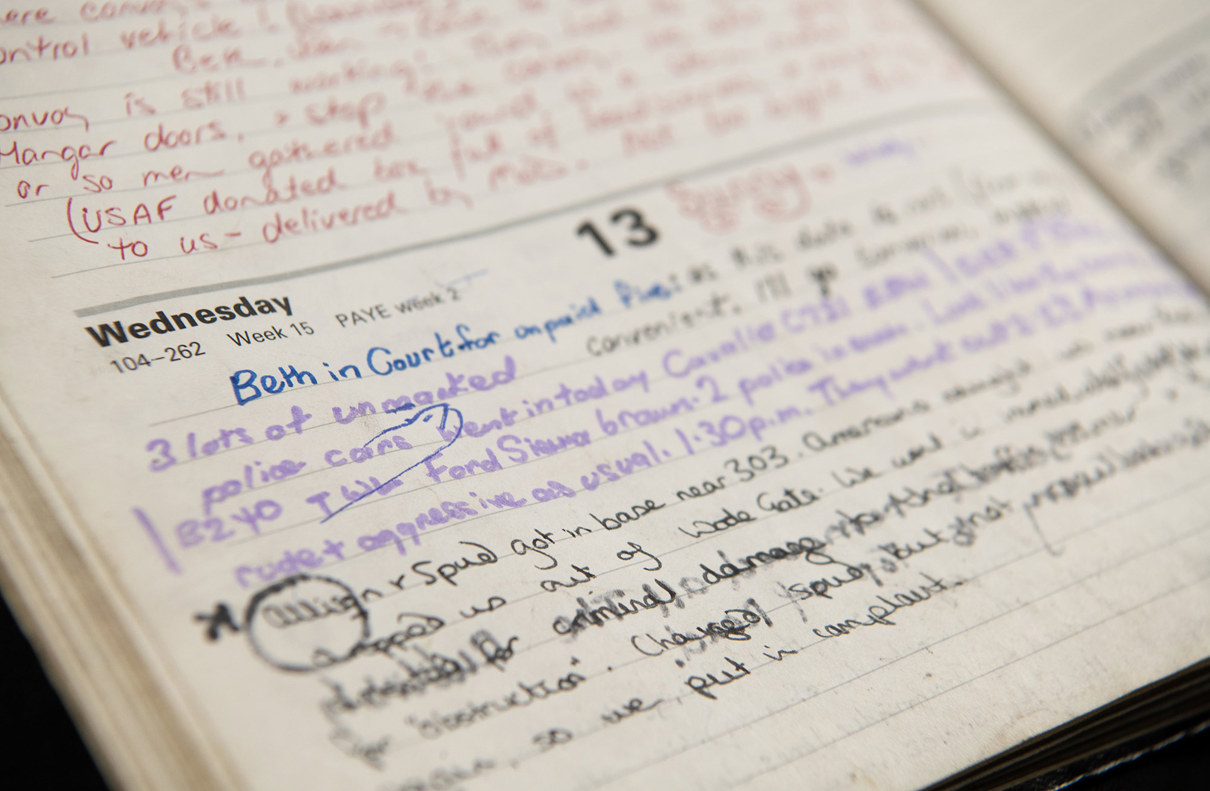

As well as their presence on the land, the activists disrupted the military's activities through non-violent direct actions. These included cutting the perimeter fence to the base, standing in front of the cruise missile convoys on the road, and entering military training grounds. "Every aspect was examined as to whether it was non-violent. And non-violence for us meant not only preventing harm to other people but preventing harm also to oneself." Despite this, their actions frequently led to arrests and legal charges of trespass or criminal damage. The women defended themselves against these charges, and this became a large part of their daily work. Junor's archive contains four boxes of legal case papers, including charge sheets, transcripts of police interviews, notes taken in court and legal research. The volume of this material, which relates to dozens of different cases, illustrates how integral this work was to their protest.

During her time living at Yellow Gate camp, Junor went to prison seven times for engaging in non-violent direct actions. "The prison system was a necessity. It was the conclusion of the non-violent direct action. There was a lot of discussion about whether to pay a fine, or to go to prison. And we decided we would go to prison, because we could not pay money to the state which we were challenging."

Junor says this also provided a context to their activism. "Being in Holloway, we had a sense again of a historical continuum, because it was a prison where suffragettes had done their time." Yet Junor doesn't see her own actions as extraordinary. "We were all just ordinary women, and we had been compelled, through our beliefs, to do this. It looks like courage, but it's just something that you do."

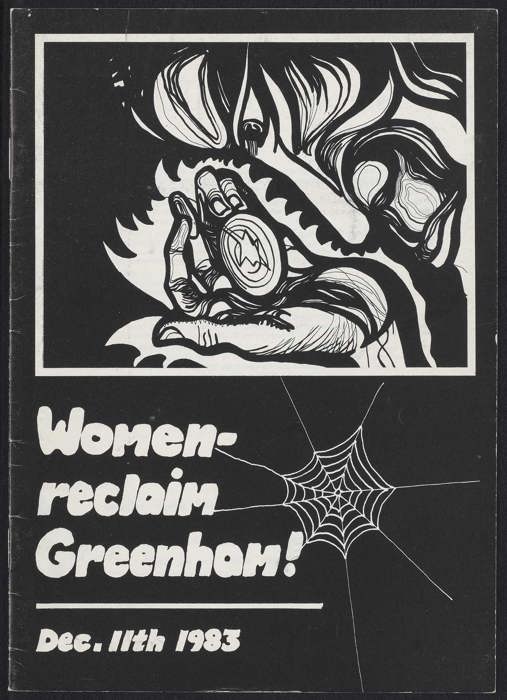

The series of papers related to the peace camp, which also include letters, camp diaries, flyers, newsletters, ephemera and sound recordings, were created by Junor and her fellow protestors as part of their organisation and activism. "These were our personal papers kept in rucksacks. Each one of us had a rucksack that was held in the back of the van – called Gladys, an old Ford transit van – and they were protected from the evictions that way." Initially, the papers were purely functional. "Everything had a purpose, they weren't kept with a view to an archive." But when the women saw how the media was distorting their experience, they began to think "we should keep these and one day tell the story of what it was really like".

When she left the camp, Junor embarked on writing a book about the women's experiences, "so I took all of my own papers and some of the Yellow Gate camp diaries with me. They were the working documents for the book". When it came to finding a home for the archive, Junor says "I had written the book in Edinburgh, so the National Library of Scotland was where I wanted these to be kept safe." Manuscripts, research and other literary papers for this book also form part of Junor's archive, along with the published book which is held in the Library's printed collections.

The attention her papers received has taken Junor by surprise. "I never, ever thought that they would come into the light of day [because] of the total vilification of the camp. I just felt they would remain hidden. This is the value of the independence of the Library, you can reveal any historical truth."

A selection of items from Junor's archive is on display in the Treasures of the National Library of Scotland exhibition until September 2025. "I think there are a lot of people who will be entirely shocked that I have done this," says Junor. But she sees a value in that, saying "I hope it will inspire women today, in whatever sphere they're working and living, to really have the courage to say 'no, that's enough'. I hope it will be an inspiration."

About the author

Hannah Grout is Assistant Curator on the Scottish Women Waging Peace project at the National Library of Scotland.

Dive deeper

Beth Junor's archive

Watch 'On site Torness 1979'