Pioneering mountain women

Introduction

Though educated and wealthy enough to travel, female climbers faced challenges their male counterparts didn't have to worry about. They were expected to behave like respectable women and their achievements were largely ignored or undervalued.

"There is no sport like mountaineering. It is the overcoming of difficulties, the mental climbing, as well as the physical, that give it such a zest."

Jane Inglis Clark in 'Pictures and Memories', 1938

Frightful, unmotherly women

As a woman in the 1800s sedate walking was thought to be a suitable and ladylike pastime. However, if you ventured into the hills without a male companion, or travelled in a remote location, your character was almost certainly called into question. Long-distance hiking, ascending mountains or climbing rockfaces prompted even more concern.

If a woman made the same climb as a man, some male climbers took it as an affront to their masculinity. However, the fiercest critics of female climbers were often other women. Some found the idea of raising a sweat, or wearing such frightful clothes, unthinkable. Some deemed adventurous women to be unmotherly.

Practical challenges

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, female travellers and climbers made adjustments to their clothing so they could move more freely. Some shortened or removed their petticoats. Others wore pantaloons, gathered at the ankle, under a wide below-the-knee skirt. Later, they resorted to wearing boys' tweed breeches, but climbing in clothes designed for a traditionally male figure could be a miserable experience.

The weight and bulk of early climbing equipment, like hemp ropes and canvas tents, posed challenges for women too, particularly when everything got wet. Travelling with guides and porters was far from easy. For one, an unchaperoned woman climbing with a male guide usually prompted social outcry. Aside from any imagined impropriety, travelling with a guide also devalued women's achievements. Men, on the other hand, could hire guides without detracting from their great heroic exploits.

Sharing and adapting their stories

Aware of potential criticism, when women hikers and climbers spoke or wrote about their adventures, they adapted the truth to satisfy their audience. For instance, they took care to mention that they bathed every day and downplayed the dangers they encountered.

While male travellers published expedition accounts with mainstream publishers or in learned society journals, women could only produce a book if there was clear evidence of sufficient demand. As a result, they often shared accounts of their travels in serial form in popular magazines. This may be one reason their achievements were overlooked or lost to history.

Now let's meet seven of these pioneering mountain women.

Constance Gordon-Cumming

Constance Gordon-Cumming was born on 26 May 1837 on the Altyre Estate, Morayshire, about 50km away from the Cairngorms. Known as 'Eka' to her friends, she was a talented painter.

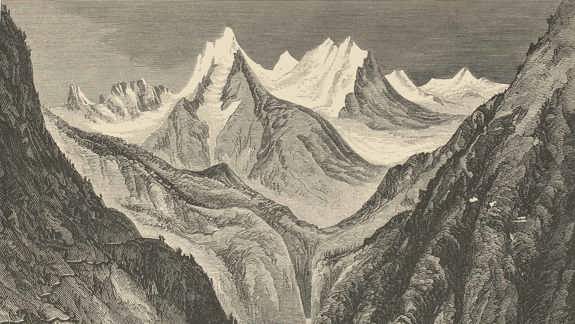

Gordon-Cumming discovered her love for travel after visiting her sister in India in 1869. While there, she travelled deep into the Himalayas. She then took extended trips to Fiji, Tahiti, Samoa, New Zealand and China.

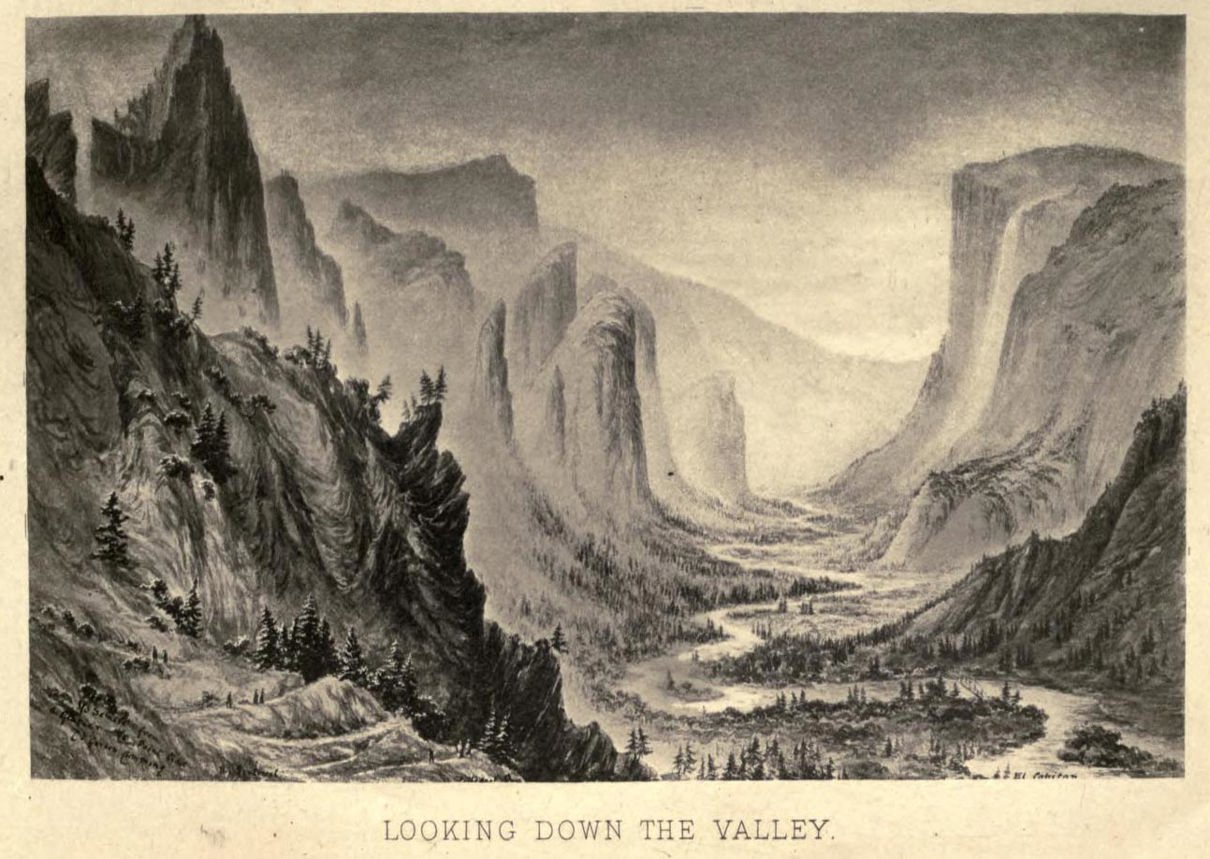

An 1878 visit to the United States was perhaps the most important and influential of Gordon-Cumming's travels. She arrived in the Yosemite Valley in California intending to stay just three days and stayed for three months.

"The first glimpse of this extraordinary combination of granite crags and stupendous waterfalls showed me plainly enough that it would take me weeks to make acquaintance with them."

Constance Gordon-Cumming writing in 'Granite Crags', 1884

Captivated by the awe-inspiring beauty of Yosemite, Cumming spent her days climbing hills and compulsively painting views of the Valley. Her stay culminated in an exhibition of her work staged in the Valley itself. It was the first exhibition of its kind.

Gordon-Cumming partly supported her travels by writing books illustrated with images from her paintings. She wanted her artwork to record parts of the world for people who were unable to experience them personally. She was so attached to her paintings that when her homeward-bound ship ran aground at Holyhead she stayed on board until they could be rescued. She later settled back in Scotland, dying in Crieff, Perthshire on 4 September 1924.

Jane Duncan

Jane Duncan was born in Glasgow in 1848 and studied in Paris. Perhaps inspired by her own studies, in the 1890s she championed access to higher education for women.

Duncan's first experience of foreign travel came in her 50s and she spent the next decade exploring the world. She visited Canada, India, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Burma (now Myanmar), Japan and the United States. As a middle-aged woman, Duncan's travels came under much scrutiny. She faced criticism for both her gender and her age.

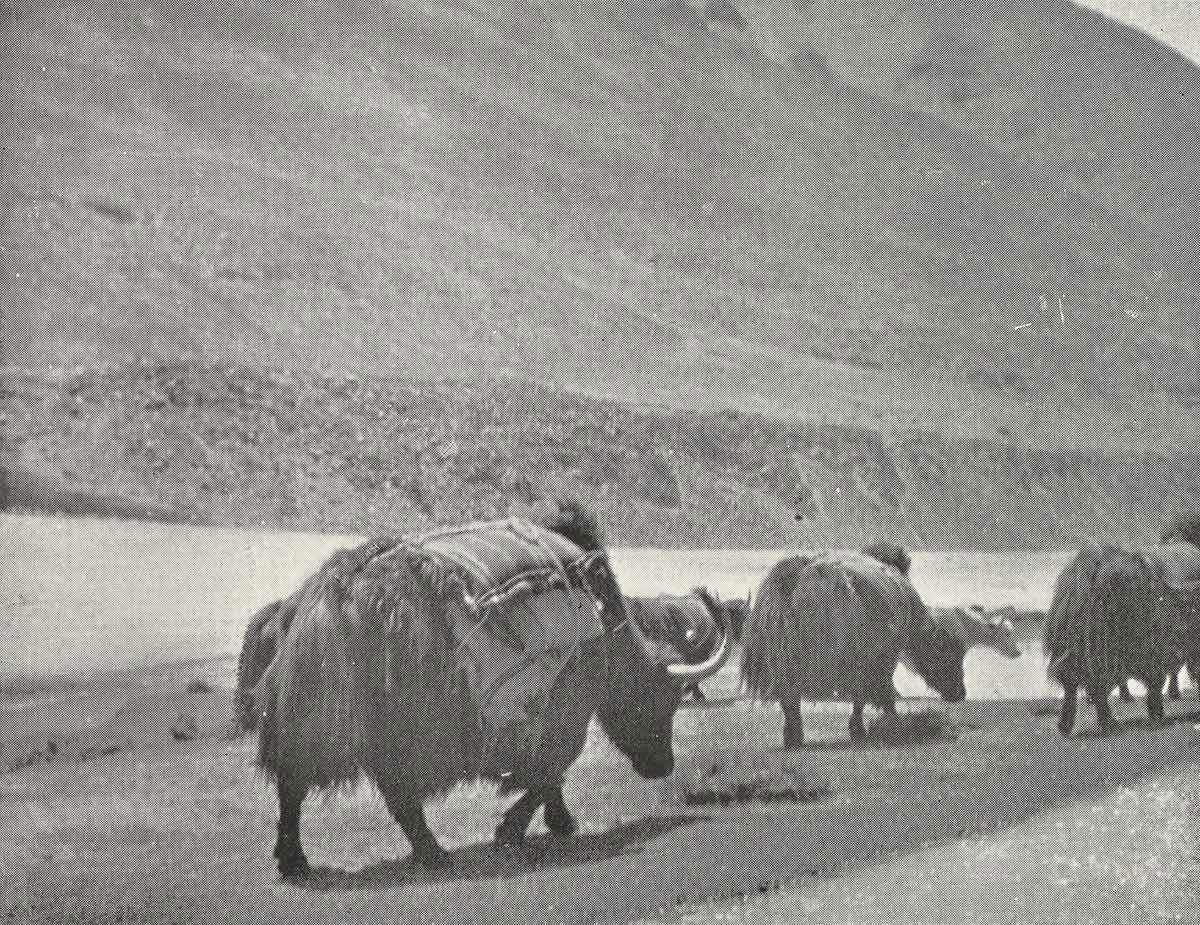

Of Duncan's many adventures, perhaps the most notable is her journey through the Chang La Pass in Ladakh, over 5300m above sea level. She was the first Western woman to make the trip.

"Perhaps women are better adapted than men to very high levels… I can only regret the feebleness of my imagination which refuses to rise into heroics over it."

Jane Duncan writing about her journey through the Chang La Pass in 'A Summer Ride through Western Tibet', 1906

By today's standards, Duncan did not travel light. Her home comforts included a bath and a set of table linens for dinner. Nevertheless, she found her experience of travel liberating and wrote about the delights of not having to 'dress' (as opposed to wearing 'mere clothes').

"Many a time after returning to civilization I longed to be in the desert again, where the crows and the goats did not care what I wore".

Jane Duncan in 'A Summer Ride through Western Tibet', 1906

In 1909 Duncan journeyed to East Africa. She fell ill on the trip and died in Naples while returning home.

Jane Inglis Clark

Born in 1859 or 1860 in Liverpool, Jane Inglis Clark moved to Edinburgh as a child. She loved hills and was an enthusiastic walker. When she began rock climbing in her late 30s she discovered a natural aptitude for tackling difficult climbing routes.

Clark went on to participate in six first-ascents of new climbing routes on Ben Nevis, alongside her husband and leading climbers of the day. Despite these achievements, Clark was unable to join the Scottish Mountaineering Club because she was a woman. In 1908, while sheltering with her daughter Mabel Jeffrey and fellow climber Lucy Smith at a boulder near Glen Dochart in Perthshire, Clark apparently announced, "It is time we started our own club for women".

Early records of the Ladies Scottish Climbing Club show that members had an unquenchable spirit of exploration and adventure. Far from taking easy or tourist routes, they found original, untested routes up almost everything. For example, Clark was part of the second ever party to climb Crowberry Ridge, then considered the most difficult climb in Britain.

The ongoing movement for women's emancipation saw more and more women take up mountaineering, and Clark was proud of her role as a pioneer. In her book 'Pictures and Memories' she writes about her belief in women's capabilities and the right to self-fulfilment.

"The troubles of life seem to fade away in the presence of the everlasting hills."

Jane Inglis Clark in 'Pictures and Memories', 1938

Clark also climbed in the Swiss Alps, Dolomites and Austrian Tyrol. She died in Edinburgh in 1950, but the club she founded in 1908 still lives on.

Ella Christie

Isabella (Ella) Robertson Christie was born on 21 April 1861 in Cockpen, near Bonnyrigg, Midlothian. From an early age Christie travelled around Europe with her wealthy parents.

After her mother died, she travelled with her father or a friend or on her own. She visited Egypt, Syria and the Holy Land and began to write about her travels. After her father's death in 1902, Christie made far more adventurous journeys. These took her to India, Kashmir, Tibet, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Malaya (now part of Malaysia) and Borneo.

Christie had an indomitable adventurous streak. She camped in a snowy Chorbat Pass, sailed a cargo ship carrying pigs, rode horse and cart in Kashmir's wilderness, and trekked 60 miles through the Deosai Mountains.

While in Japan Christie became fascinated by the Japanese formal style of gardening. When she returned to Cowden Castle, the estate her father bought in 1865, she was inspired to create a Japanese garden there.

In 1912 Christie made a trip to what was then the Russian Empire. Starting in Saint Petersburg she travelled by train, steamer and carriage to Tashkent, Samarkand in present-day Uzbekistan. She was the first British woman to visit the Khanate of Khiva which covered present-day western Uzbekistan, south-western Kazakhstan and much of Turkmenistan. Christie kept diaries of her travels and later wrote about her trips to the Russian Empire in the book 'Through Khiva to golden Samarkand'.

When the Royal Geographical Society voted to allow women to be elected as members of the society in 1913, Christie was in the first selection of female Fellows. She died in 1949, aged 87, in Edinburgh.

Isobel Wylie Hutchison

Born in 1889 at Carlowrie Castle in West Lothian, at the dawn of moving pictures, Isobel Wylie Hutchison grew up to become a respected filmmaker.

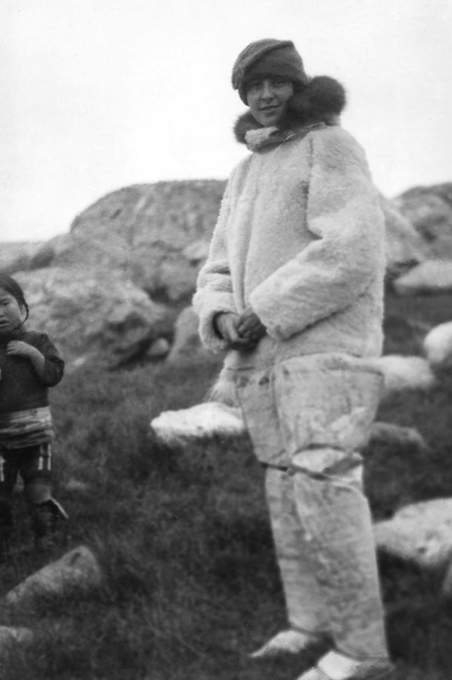

Until her mid-30s, Hutchison lived a quiet, sheltered life, enjoying long solitary walks. Then, in 1924, she walked the length of the Outer Hebrides, submitting an account of her trek to 'National Geographic' magazine. She used the magazine's fee to fund a trip to Iceland and spent extended periods in Greenland, where she scaled the mountain of Qilertinguit.

In 1934 Hutchison set out for Alaska, travelling by coastal steamer from Vancouver to Skagway and then overland to Nome. She found a small freighter to take her along the north coast of Alaska and travelled 120 miles by dog sledge before returning to Alberta on a mail plane.

Throughout the Arctic, Hutchison filmed everything she saw around her – the landscape, the wildflowers and the daily lives of the Inuit. Other travellers of the time documented their journeys in books and articles, but didn't dwell on domestic details like hunting seals from a kayak of collecting ice for water.

The Royal Scottish Geographical Society awarded Hutchison its third Mungo Park Medal in recognition of her original and valuable research in Iceland, Greenland and Arctic Alaska. Respected as a botanist as well as a filmmaker, many of Hutchison's plant collections ended up in the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh or London's Natural History Museum and Kew Gardens.

Hutchison wrote four volumes of poetry and several travel books, including 'North to the Rime-Ringed Sun' and 'Stepping Stones from Alaska to Asia'. In later life she gave lectures using her own films and lantern slides. She had a long connection with the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, acting as Honorary Editor of its magazine and as Vice-President. She died at Carlowrie Castle in 1982.

Nan Shepherd

Nan Shepherd was born on 11 Feb 1893 at Westerton Cottage, Cults, now a suburb of Aberdeen. Shepherd is best known for her non-fiction masterpiece, 'The Living Mountain'.

Shepherd's home on the outskirts of Aberdeen provided a direct route to the mountains along the Deeside valley and she spent much of her free time outdoors. She walked with friends, but also on her own.

Shepherd's first climbs in the Cairngorms, including an ascent of Ben Macdui, took place in 1928. Over the years, she developed a relationship with the mountains that felt like a lasting friendship. Shepherd loved the Cairngorm's tiny details as much as their height and remoteness. Her experiences there moved her to write poetry about what she saw and how she felt.

"Summer on the high plateau can be delectable as honey; it can also be a roaring scourge. To those who love the place, both are good, since both are part of its essential nature."

Nan Shepherd in 'The Living Mountain', 1977

Shepherd's first novel, 'The Quarry Wood', was published in 1928 and proved to be a success. Two further novels, 'The Weatherhouse' and 'A Pass in the Grampians', performed similarly well. However, Shepherd's most famous work, 'The Living Mountain', was not published until 1977. Mainstream success had to wait until the book was reissued decades after her death.

Regarded as a seminal work of nature writing, 'The Living Mountain' foreshadows contemporary ideas of mindfulness and wellbeing. For Shepherd, simply being in and with the mountains was enough. She died in Aberdeen in 1981.

Una Cameron

Una Cameron was born in West Linton, Peeblesshire, in 1904. Her father was a landowner, her mother a member of the Dewar whisky family.

While attending art college in Rome, Cameron became interested in climbing, which she pursued mostly as a means of personal fulfilment. Tall, androgynous and clad in trousers, Cameron attracted attention wherever she went.

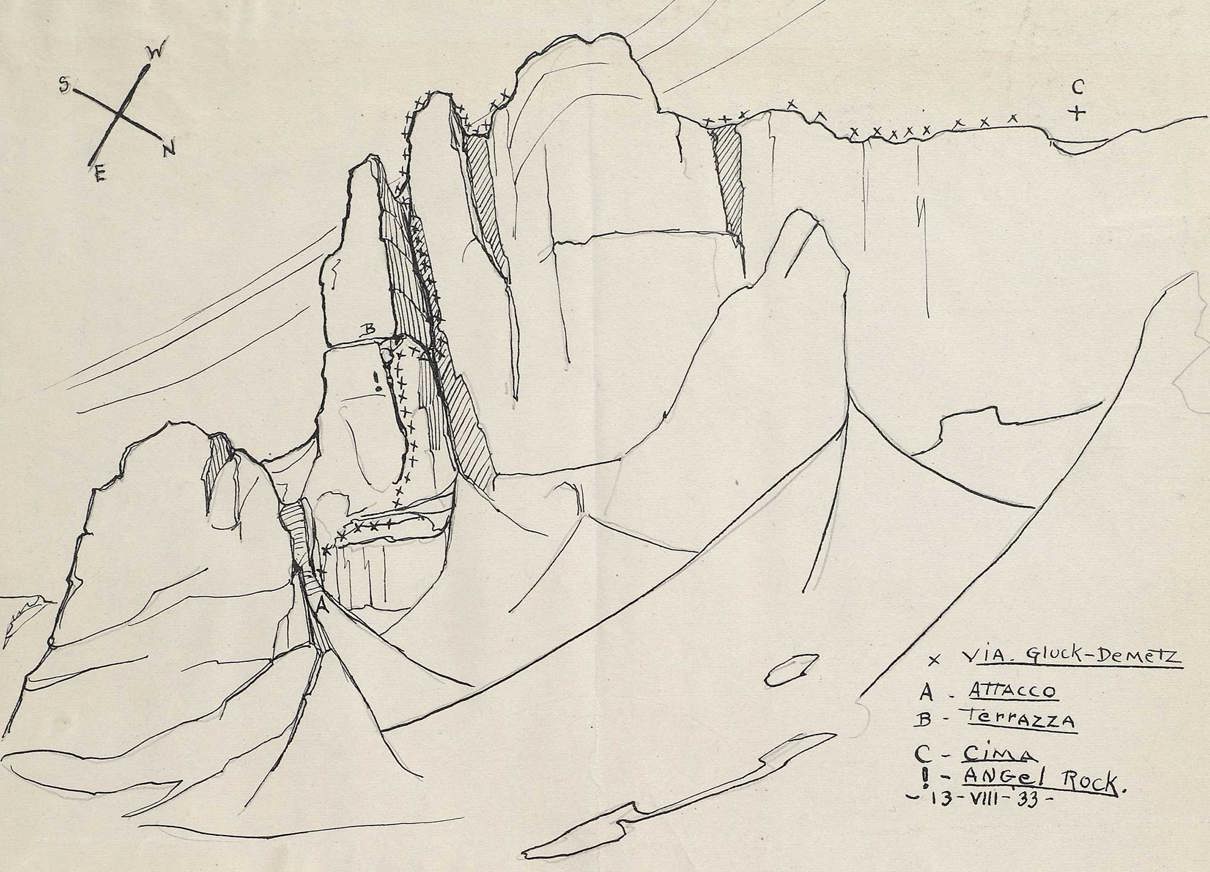

During the 1930s, she made many first ascents in the Alps and the Caucasus mountains, which sit at the border of Europe and Asia. She described her climbs in the book 'A Good Line'.

Fluent in both Italian and French, Cameron had a villa built in Courmayeur, Italy, which enabled her to explore the south side of Mont Blanc at her leisure. Between 1933 and 1939 she traversed the peak in almost every way possible.

In 1935, Cameron and Dora de Beer became the first British women to make a complete ascent of the longest ridge in the Alps. With 4,500 metres of ascent, the Peuterey Integral takes about two to three days to climb.

Cameron was a lifelong member of the Ladies' Alpine Club and, through her outstanding climbing record, was one of the most prominent contributors to its journal. She was elected President of the club in 1957, its jubilee year.

A lasting legacy

Of course, like most other female climbers of the time, Cameron had the financial means to fund her interest. In the early 1900s, only the wealthy had the leisure time to enjoy long weekends in the highlands of Scotland or make trips to the Alps, let alone further afield.

Nevertheless, these pioneering women broke down barriers that prevented women from enjoying pursuits only deemed suitable for men. In the process, they left a quiet legacy. Nan Shepherd helped shape our relationships with wild spaces. Isobel Wylie Hutchison gathered precious plant samples while filming Inuit life. And climbers like Jane Inglis Clark and Una Cameron redefined the idea of women climbers. They made first ascents and become leaders and mentors for others.

The spirit of these pioneers can be seen in later Scottish climbers too, like Evelyn McNicol, the youngest member of the first all-woman expedition to the Himalayas in 1955. Almost 50 years later, Vicky Jack became the (then) oldest British woman to climb Everest, aged 50, a feat she describes as being more about mental strength than physical ability. And how did she develop that mental strength? Through, she says, "all those years of going out and bashing the hills in Scotland in all weathers".

Dive deeper

Climbing films in the Moving Image Archive

Sports and recreation