Robert Burns and his "history of myself"

Introduction

"A history of myself"

On a summer's day in 1787, Scottish poet Robert Burns sent a letter to his friend John Moore, a Glasgow-educated doctor who was then living in London. Writing at his home in Mauchline, East Ayrshire, Burns begins by saying he has been "rambling over the country" but now, after being taken ill, is in a bored, "miserable fog". To lift his spirits, he writes, he has decided to give Moore "a history of myself".

The result is a lengthy letter full of background information and self-aware reflections. While providing biographical detail, the document also reveals hints about Burns's personality and his relationships with others, including his father.

"In my seventeenth year, to give my manners a brush, I went to a country dancing school. My father had an unaccountable antipathy against these meetings; and my going was, what to this hour I repent, in absolute defiance of his commands."

Extract of a letter from Robert Burns to Dr John Moore, 2 August 1787

Robert Burns's early life

Born on 25 January 1759, Robert Burns spent the first seven years of his life in a cottage built by his tenant-farmer father in Alloway, Ayrshire. The Burns family later moved to nearby Mount Oliphant Farm where Burns worked on the land. Doing a man's job while still a boy combined with a bout of rheumatic fever sparked the heart disease that eventually led to Burns's early death.

Despite his farming responsibilities, the young Burns attended a local school set up by his father and four neighbours. Additional instruction was given in Latin, French and mathematics.

Engraved portrait of Robert Burns. (Engraver Henry Robinson, active 1827 to 1872 and artist Alexander Nasmyth, 1758 to 1840.)

When Burns was about 15, while still working on his father's farm, he began writing poetry. In his letter to Moore, Burns describes his new interest as "the sin of rhyme".

"This kind of life, the chearless gloom of a hermit with the unceasing moil of a galley-slave, brought me to my sixteenth year; a little before which period I first committed the sin of RHYME."

Extract of a letter from Robert Burns to Dr John Moore, 2 August 1787

Burns's Commonplace Book

After his father died in 1784, Burns and his family moved once more. The years at Mossgiel Farm, near Mauchline, were some of Burns's most prolific. He made observations on poetry and moral philosophy in addition to composing his own original works. On the first page of what's now known as the 'First Commonplace Book', he explains that he wrote down his poems and other notes so people might see how "a ploughman" thought and felt.

"It may be some form of entertainment to a curious observer of human nature to see how a ploughman thinks and feels, under the pressure of Love, Ambition, Anxiety, Grief with the like cares and passions, which, however diversified by the modes and manners of life, operate pretty much alike, I believe, in all the species."

Extract from the 'First Commonplace Book' of Robert Burns, 1783

First page from Robert Burns's 'First Commonplace Book'.

Some of the works in the 'First Commonplace Book' were later published in Burns's first poetry collection.

The 'First Commonplace Book' is part of the 'Blavatnik Honresfield collection. A UK-wide consortium, including the National Library of Scotland, came together to raise the money required to purchase the collection. The 'First Commonplace Book' is owned jointly by the National Library of Scotland and the National Trust for Scotland and is normally stored at the National Library.

Burns and the Kirk

One of the pieces Burns wrote during this period was the satirical poem 'Holy Willie's Prayer' (though it wasn't part of the 'First Commonplace Book').

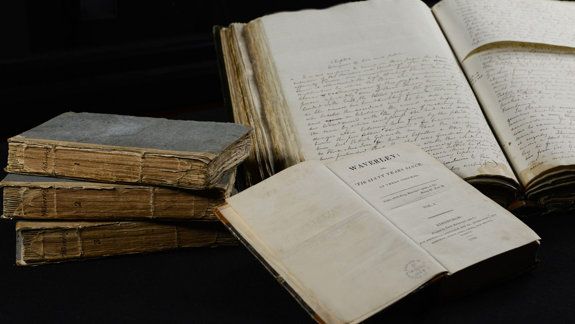

Robert Burns's 'Holy Willie's Prayer', from the Glenriddell Manuscripts circa 1791.

Burns's poetic imagination had always been thrilled by the vivid stories and beautiful language of the Bible and he quoted widely from it in his letters. However, the young Burns's choice of friends, along with his casual relationships with women, brought him into frequent conflict with the Church of Scotland, known as the 'Kirk'.

In the Glenriddell Manuscripts, written several years after Burns first wrote 'Holy Willie's Prayer', Burns outlines his thought process. He explains that 'Holy Willie's Prayer' was written as an act of revenge against local farmer William Fisher. Fisher was an elder at Mauchline Kirk, and the Kirk Session had initiated disciplinary action against Burns's friend Gavin Hamilton for failing to attend church regularly. Although only an anonymous version in 1789 was printed during Burns’s lifetime, the poem, unsurprisingly, prompted concern from the Kirk.

"Holy Willie's Prayer next made its appearance, and alarmed the kirk-Session so much that they held three several meetings to look over their holy artillery, [to see] if any of it was pointed against profane Rhymers. — Unluckily for me, my idle wanderings led me, on another side, point blank within the reach of their heaviest metal."

Extract of a letter from Robert Burns to Dr John Moore, 2 August 1787

Forsaking Scotland?

By 1786, Robert Burns found himself in farming and personal difficulties. Mossgiel Farm was failing to make a profit and his willingness to marry Jean Armour, who was pregnant by him, was opposed by her father. The only way out, it seemed to Burns, was to emigrate.

Burns's plans to sail for Jamaica were well advanced when events took an unexpected turn. In order to finance the voyage, Burns followed the advice of a local lawyer and published some of his poems.

"I had taken the last farewel of my few friends; my chest was on the road to Greenock; I had composed my last song I should ever measure in Caledonia…when a letter…overthrew all my schemes by rousing my poetic ambition."

Extract of a letter from Robert Burns to Dr John Moore, 2 August 1787

'Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect' was the result, Burns's first published collection of poems. Printed by John Wilson of Kilmarnock in July 1786, the book is also known as 'The Kilmarnock Edition'.

The entire print-run of 612 copies sold out within a month, justifying Burns's belief in his writing abilities and the merit of the poems. He soon reconsidered his plans to emigrate.

Admired by Edinburgh society

Following the success of the 'Kilmarnock Edition', Burns visited Edinburgh in order to further his literary ambitions. Everyone in the city was eager to meet the man described by writer and reviewer Henry Mackenzie as the "Heaven-taught ploughman" and Burns was admired by high society.

"At Edinr I was in a new world. I mingled among many classes of men, but all of them new to me; and I was all attention "to catch the manners living as they rise"".

Extract of a letter from Robert Burns to Dr John Moore, 2 August 1787

Over the following 18 months Burns often stayed in Edinburgh as he arranged the publication of a second edition of his poems. He first lived in Baxter's Close, off the Lawnmarket, and later in newly built St James Square, at the east end of the New Town.

While joining in the Edinburgh social round, Burns met Agnes Maclehose, an educated woman who was separated from her husband. Burns and Maclehose established a passionate platonic relationship and began writing to one another under the pseudonyms 'Sylvander' and 'Clarinda'. Their correspondence is one of the most famous examples of stylised romantic letter-writing. Even more famous is 'Ae Fond Kiss', the parting song Burns sent to Maclehose after their final meeting in December 1791.

Travels and Scottish songs

By the time Burns wrote his letter to Moore in 1787, he was perceived by many as Scotland's national bard. This status gave him a strong commercial motive to visit rural subscribers to introduce the new 'Edinburgh Edition' of his poems.

In May, Burns set off on a series of tours around Scotland that he described as a "slight pilgrimage to the classic scenes of this country". Riding on horseback, he travelled first to the Borders and later to central Scotland and the Highlands. While at home in-between two of these trips, Burns wrote his biographical letter to Moore.

The same year, Burns became involved in Edinburgh music-seller James Johnson's project to collect and publish the words and music of Scottish songs. Johnson had just published the first volume of his book 'The Scots Musical Museum' and Burns made a major contribution to its later instalments.

Largely due to Burns, Johnson's publication eventually ran to six volumes, each containing 100 songs. The fifth included the now world-famous song, 'Auld Lang Syne'. Though Burns collected the details of this old folk song on his travels, he likely adapted and extended the lyrics. Today, 'Auld Lang Syne' is generally attributed to him.

Burns also collaborated with musical enthusiast George Thomson, who published 'classical' musical arrangements of Scottish folk songs. Burns himself played the fiddle and he even sang his own songs at celebrations. The first volume of Thomson's 'A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs' was issued in 1793.

The Glenriddell Manuscripts

From 1788, Burns attempted to farm at Ellisland in Dumfriesshire, but his efforts were fruitless. However, a new friendship with neighbour Robert Riddell of Glenriddell proved more rewarding.

Part of the landed gentry, the Riddells enjoyed the company of their tenant-farmer neighbour and appreciated his literary talents. Riddell encouraged Burns to write by presenting him with two leather-bound notebooks and asking Burns to fill each with poetry and prose. Burns gave one volume, featuring more than 50 poems, back to Riddell in April 1791. Today, the two notebooks house the single largest collection of Burns's manuscripts in existence. They are recognised as one of the main treasures at the National Library of Scotland.

Preface to the first volume of the Glenriddell Manuscripts.

'Tam O' Shanter'

Burns described the Riddells' home, Friars' Carse, as, "positively the most beautiful spot in the lowlands of Scotland". On one of his frequent visits there, Burns was introduced to the antiquary Francis Grose.

Grose was touring Scotland to gather material for his book 'The Antiquities of Scotland'. When Burns suggested Grose include Alloway Kirk in the publication, he agreed so long as Burns wrote an accompanying poem. The bargain was sealed with the mock-heroic epic 'Tam O' Shanter', which Burns wrote in 1790.

Set in Alloway, where Burns spent the early years of his life, 'Tam O' Shanter' tells the story of farmer Tam, who meets a coven of witches while riding home after a night of drinking. Though Tam escapes the witches, one snatches the tail from his horse as he gets away.

In Burns's day, many people still believed in witchcraft. When he was a child, Burns himself learned about folklore from his nurse.

"In my infant and boyish days … I owed much to an old Maid of my Mother's, remarkable for her ignorance, credulity and superstition. – She had … the largest collection … of tales and songs concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks … and other trumpery. – This cultivated the latent seeds of Poesy; but had so strong an effect on my imagination, that to this hour, in my nocturnal rambles, I sometimes keep a sharp look-out in suspicious places."

Extract of a letter from Robert Burns to Dr John Moore, 2 August 1787

'Tam O'Shanter' is an engaging, humorous read that remains popular today. Still performed regularly, the poem gave its name to a traditional flat, wool hat with a bobble, which was popular with farmers at the time. In an entirely different context, the tea clipper 'Cutty Sark', built in Scotland in 1869, was named after one of the witches from the poem. The ship's carved figurehead depicts the witch clutching the horsetail she snatched as Tam escaped.

Burns's final years

Burns spent the final years of his life in Dumfriesshire. In September 1789 he began work for the Excise at Dumfries. Though he performed his duties diligently and compassionately, charges of political disloyalty were raised against him.

Here he read the complete works of Shakespeare, but his failing health – which he sought to remedy by sea-bathing – overshadowed his own literary and musical output. Years of hard physical labour working on a series of unproductive farms had aggravated Burns's long-standing heart condition and he died, at the age of 37, on 21 July 1796.

On the day of his funeral, Burns's wife Jean Amour gave birth to their youngest son, Maxwell.

"My wife is hourly expecting to be put to bed. Good God! what a situation for her to be in, poor girl, without a friend! I returned from sea-bathing quarters today, and my medical friends would almost persuade me that I am better, but I think and feel that my strength is so gone that the disorder will prove fatal to me."

Extract from a letter from Robert Burns to James Armour, his father-in-law, 18 July 1796

Robert Burns's legacy

In his letter to Moore, Burns wrote, "my name has made a small noise in the country". Today he has left his stamp on the world. By 1986, it's estimated that over 2,000 editions of Burns's poetry had been published. That's an average of ten editions every year since 1786.

"I weighed my productions as impartially as in my power; I thought they had merit; and 'twas a delicious idea that I would be called a clever fellow…"

Extract of a letter from Robert Burns to Dr John Moore, 2 August 1787

The 19th-century scholar and educationalist JS Blackie summed up Burns's importance to Scotland and the Scots with the words, "When Scotland forgets Burns, then history will forget Scotland". Burns is, however, still very much in mind. In 2009, he was voted the 'Greatest Scot' in a public vote run by Scottish television channel STV. He again topped the polls in the National Trust's 2016 'Great Scot' survey and the Scotsman's 2023 'most influential Scot of all time' vote.

Scholars continue to study Burns's work, while merchandise and social events endure. You can buy Burns badges, dress-up dolls and whisky. 250 years after he was born you could even buy a Robert Burns Coca-Cola bottle. And every year, the song 'Auld Lang Syne' is sung to ring in the New Year across the English-speaking world. Perhaps the most pervasive celebration of Burns is, however, his birthday. On 25 January, people gather together around the globe to mark his birth with parties and dinners. Recitals of poems like 'Tam O'Shanter' or 'A Red, Red Rose' show just how beloved Burns and his work remains.

"Till a' the seas gang dry, my Dear,

And the rocks melt wi' the sun:

I will luve thee still, my dear,

While the sands o'life shall run."

Verse from 'A Red, Red Rose' by Robert Burns

Dive deeper

Works of Robert Burns

Robert Burns archives and manuscripts collection

Literature and poetry