How Martin Luther sparked the reformation

Introduction

What was the Reformation?

The Reformation was a religious revolution that took place in Europe in the 1500s. Until then, the main religion in Western Europe was Catholicism, part of the Christian faith. At that time, the Catholic Church was powerful and wealthy. With political influence stretching across the continent, many people wanted to see it reformed.

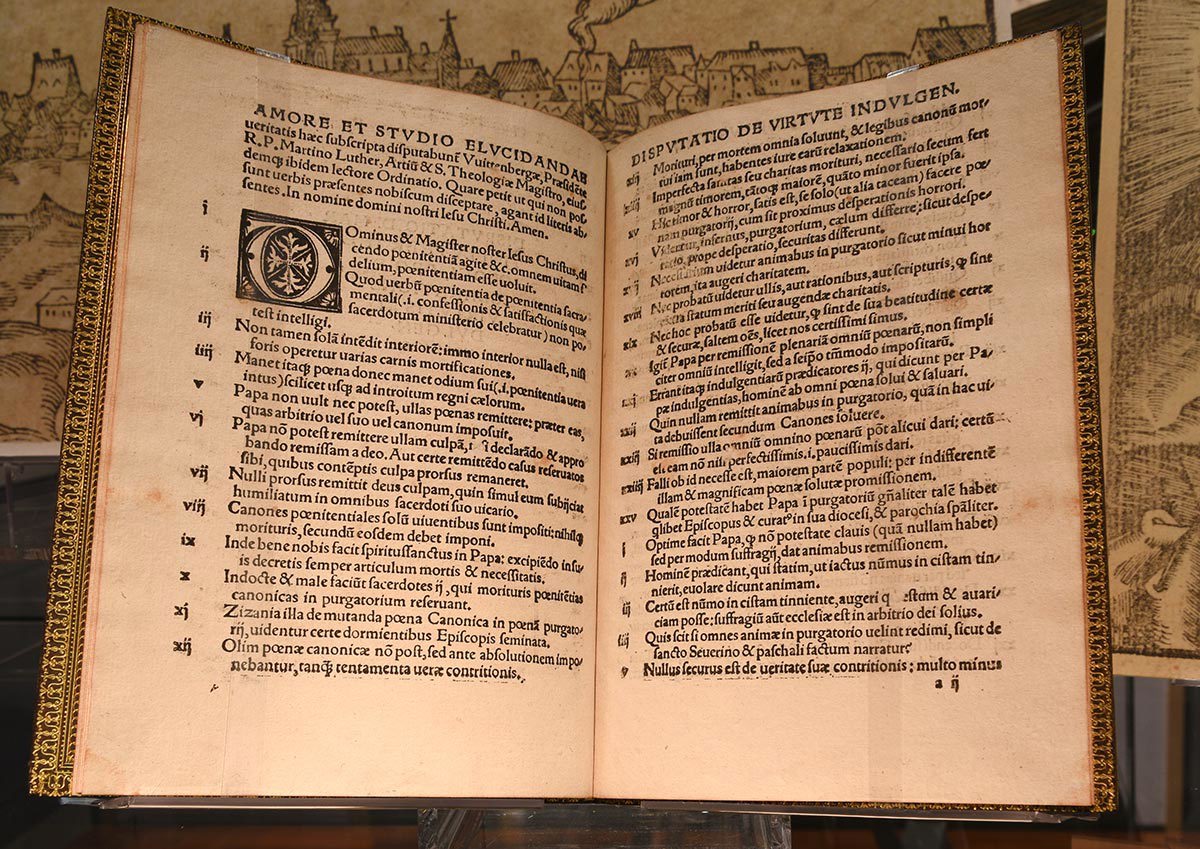

Martin Luther didn't set out to break away from the Catholic Church. But on 31 October 1517 he's said to have nailed a document to a church door in Wittenberg which questioned its practices and authority. Known as the '95 Theses', Luther's document provided a catalyst that splintered Catholic Europe and changed the course of history.

During the Reformation, people who protested against the Catholic Church became known as 'protestants'. When the Church resisted change, some set up new 'Protestant' churches. In Germany, followers of Martin Luther created the Lutheran Church. Later, in England, King Henry VIII founded the Church of England.

Who was Martin Luther?

Martin Luther was born in Eisleben, Saxony (now modern-day Germany) in 1483. He studied at the University of Erfurt and, in 1505, entered the monastery of the Augustinian Hermits in the same city. Luther is said to have vowed to become a monk after being caught in a terrifying thunderstorm. Fearing for his life, he cried out to Saint Anne, promising to dedicate his life to God if he were saved.

After joining the Augustinian order, Luther lectured in moral philosophy at the University of Wittenberg. He became a professor of Biblical studies, focusing on religious belief and the nature of God.

For Luther, the sole source of religious authority came from the Bible. In his mind, Christians were only answerable to God, and mediation of God's grace via the church was not a necessity. When Luther shared these views publicly, he was branded a heretic.

Indulgences and the '95 Theses'

The '95 Theses' posed questions about the church's sale of 'indulgences', a means by which Catholics could be exempted from punishment for certain sins. Like taking out an insurance policy against the wrath of God, buying an indulgence was believed to protect you from being punished for your sins after death. While seemingly serving a purpose to churchgoers, indulgences also provided a lucrative source of income for the Pope, the head of the Catholic Church, and his papal administration.

Luther heard about the hard sale of indulgences from parishioners who came to him to confess their sins. Wanting to provoke academic debate around the issue, he wrote the '95 Theses' in Latin using the full title, 'Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences'. He began with the line, "Out of love for the truth and from desire to elucidate it, the Reverend Father Martin Luther … intends to defend the following statements and to dispute on them".

Though Luther wasn't the first person to criticise the sale of indulgences, his '95 Theses' struck a chord with others who thought the practice was corrupt. Thanks to a relatively new technology, the printing press, this list of academic provocations was able to be widely copied and shared. The result was a very public challenge against the Church.

Copies of the '95 Theses' were printed in both broadside and book form. In 1518, Luther translated them from Latin into German, further widening their audience. This German translation became a Reformation bestseller, with 24 reprints and two other translations produced in just two years. They spread like wildfire throughout Germany and Europe.

How the Church responded

The head of the Catholic Church at the time was Pope Leo X, a Medici Renaissance prince. While taking care of the spiritual welfare of the Church, Leo also wanted to maintain the political power held by the Vatican State. The last thing he needed was this attack on his authority.

Intent on nipping the challenge in the bud, Leo set out to silence the unruly monk. In 1518, he summoned Luther to Rome. However, when Luther's patron Friedrich III of Saxony intervened, Luther's case was moved to German soil.

Meeting representatives of the Pope in the Bavarian city of Augsburg, Luther was interrogated at an official meeting known as a 'diet'. Neither Luther nor his interrogators changed their positions during this meeting. Luther stuck by his fervently held beliefs. The Church maintained that Catholics were compelled to obey the Pope, since he was God's representative on Earth.

The excommunication

Two years later, on 15 June 1520, the Pope issued Luther with an order known as a 'Papal bull'. In it, the Pope threatened Luther with excommunication unless he recanted 41 of, what the Church deemed points of deviancy to Christian teaching, from his '95 Theses'. The order began with the words, "Rise up oh Lord for the foxes have risen to destroy your vineyard".

It took several months for the bull to arrive in Wittenberg and Luther gained additional breathing space thanks to political intrigues between the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Charles ruled a collection of territories in Western and Central Europe stretching from the Netherlands and Germany to Austria and Italy.

Luther put this delay to good use, writing a number of publications now seen as crucial to the Reformation. One called for German nobles to reform Christianity. Containing a comprehensive social, educational and economic reform programme, this address sold 4,000 copies in a matter of days. Another set out Luther's revolutionary view that Christians were only answerable to God and their conscience, based on the Bible.

The bull asking Luther to recant finally arrived in Wittenberg in October 1520. When Luther received the order, he had 60 days to recant. After this period, he tossed the bull onto a bonfire in a public square along with books that set out the legal powers of the Church.

In response, the Pope followed through on his threat. He issued another bull and excommunicated Luther as a heretic. Luther could no longer be a monk or a priest and he was banned from preaching or taking part in the sacraments.

The imperial ban

Three months later, Luther was summoned to another official meeting, this time in the German city of Worms. While travelling there he preached to large crowds who came out to greet him.

At Worms, Luther was once again asked to recant his writings. He refused, saying he felt no obligation to the authority of the Pope. He concluded with the words, "Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me. Amen".

This time, Charles V took action by imposing an 'imperial ban' against Luther. The uncooperative monk was now an outlaw. His works couldn't be printed, sold or distributed. No one was allowed to house or help him. Worse, anyone could kill him without reprisal.

Fortunately, Friedrich III of Saxony again intervened. Friedrich arranged for Luther to be abducted on his way back from Worms and taken to Wartburg Castle for his own safety.

The Luther Bible

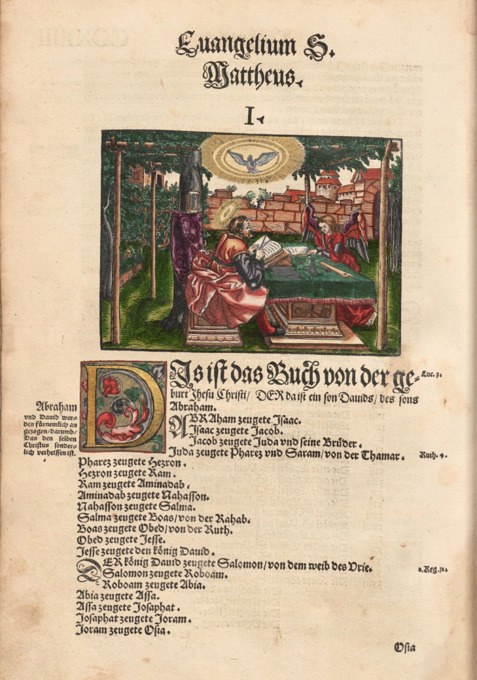

While keeping safe at Wartburg Castle, Luther again made good use of his time. In just eleven weeks he translated the New Testament from its original Greek into German.

While Luther viewed the Bible as the sole source of religious authority, he knew it was only accessible to people able to read Greek, like priests and scholars. Luther's Bible was different. Written in familiar German, it was accessible to anyone who could read, or anyone able to listen to others reading from it. Luther even included wood-cut illustrations to bring the Bible stories to life.

Put on sale at the Leipzig Book Fair in 1522, Luther's German translation of the Bible sold out almost at once. A second edition followed three months later. Within a year, 13 authorised editions had appeared, along with 50 pirated versions.

The Tyndale Bible

Around the same time, English scholar William Tyndale translated the New Testament from Greek into English. Like Luther, Tyndale believed in the central importance of the Bible and wanted everyone to be able to read it. When the Church prevented him from producing a translation in England, Tyndale was forced to print it in Germany.

In 1526 the first copies of Tyndale's Bible were smuggled back into England, where many were seized and publicly burnt. Ten years later, while Tyndale was working on a translation of the Old Testament, he was captured, tried for heresy as a Lutheran and burned at the stake. Despite Luther's own run-ins with both Church and state, he ultimately had a happier fate than Tyndale.

Luther's final years

After spending almost a year hiding out in Wartburg, Luther returned to Wittenberg in 1522. By this time, the movement to force the Church to change had grown. New reformers were leading the way across Europe and public riots and protests were happening.

In 1525, Luther broke with Catholic protocol and got married. Despite the Catholic Church's requirement for priests to remain celibate, Luther had found nothing in the Bible to suggest this should be the case. By getting married he, once again, showed that it was the Bible, not the Church, who had authority over him. Together with his bride, the former nun Katharina von Bora, Luther went on to have six children.

Despite the actions of the Pope and Charles V, Luther continued to preach and write, even in ill health. He died in 1546 and is buried in Wittenberg's Castle Church, not far from where his world-changing Theses were first said to have been shared.

Dive deeper

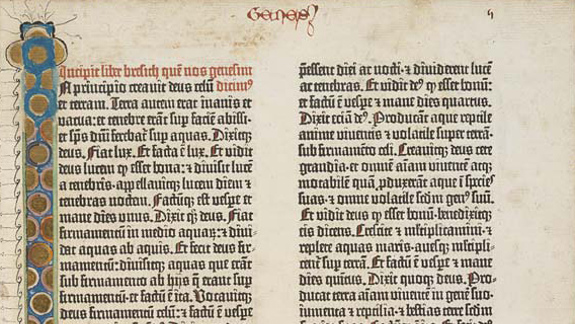

The Gutenberg Bible

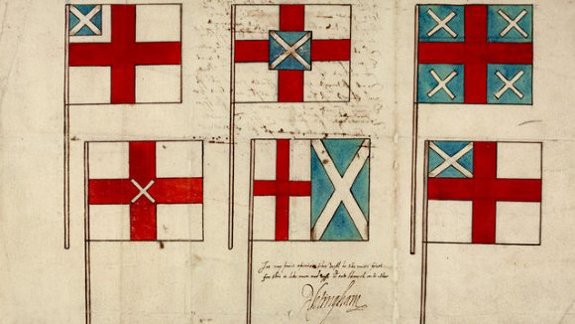

James VI and the Union of the Crowns

Early manuscripts