The National Library of Scotland has rich illustrated holdings scattered throughout the collections.

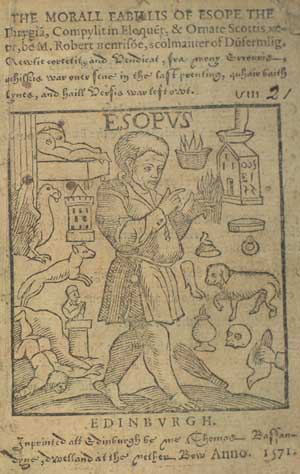

Following the medieval tradition of finely decorated and illuminated manuscripts, the first Scottish printed books had elaborate woodcuts (images printed from a stamp carved out of wood). Colour was sometimes applied by hand to early Scottish books after printing, and some liturgical books contain printing in red, such as the Aberdeen Breviary printed at Edinburgh in 1509 (shelfmarks: Sa.3, F.6.f.5).

However, early Scottish printing has nothing to compare with elaborately decorated continental books such as the Roman Breviary printed by Nicolaus Jenson at Venice in 1478 (shelfmark: Inc.118).

The Library's one example of a blockbook (shelfmark: Xyl), a book where each page was carved from a single piece of wood, with images and text on devotional subjects, aimed at those at the margins of literacy, is not Scottish.

In the Library's collections of early foreign books there are many woodcut illustrations: astronomical plans, portraits of writers, scenery and buildings. Scotland, though, produced relatively little in terms of book illustration until the 18th century, mainly because of the skill and equipment required.

Illustrated books by Scots were printed abroad, such as George Chalmers' 'Emblemata' (Venice, 1627, shelfmark: RB.s.2045), the first emblem book by a Scottish author, or John Slezer's 'Theatrum Scotiae' (London, 1693, shelfmark: RB.l.36) with its magnificent plates of Scottish landscapes and towns. Scottish designers, gardeners and architects produced some fine illustrated books, such as Robert Adam's 'Ruins of the palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro' (London, 1764, shelfmark: FB.el.108) or George Richardson's 'Book of Ceilings' (London, 1776, FB.el.132).

In the early 19th century, it became the norm to engrave images on steel plates rather than the softer copper plates which had in turn superseded the woodcut.

Books printed in Scotland began to use more illustrations. Walter Scott's works immediately attracted those with a visual imagination, and paintings and drawings based on the Waverley novels (like those by Alexander Nasmyth, of which we hold the originals, or James Skene) were soon published as engravings.

Edinburgh engravers such as the Lizars family showed that Scotland could take a lead in producing quality illustrative work. By the mid-19th century, it was possible to produce engravings of adequate quality to record accurate information of archaeological value, as is shown by Robert Billings' 'Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland' (Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1852, shelfmark: FB.el.127), which has fine plates of Scottish monuments such as Rosslyn Chapel.

In keeping with the early 19th-century rise in the importance of Scottish book illustration, the Faculty of Advocates seems to have developed an eye for illustrated books, adding the great coloured plate books in the Egypte collection, as well as natural history books with fine plates of birds and animals.

The image became particularly important in Scottish book culture in the 19th century. Lithography (printing from an image drawn on stone) arrived in Scotland by 1820, although the great Scottish artist David Roberts had his views of the Holy Land lithographed in London. Eventually, machine colour-printing transformed the book industry. As photography became established, it became possible to print illustrated books cheaply.

When the art of cover illustration developed as well, Scotland produced some of the world's leading book artists:

- Phoebe Anna Traquair with her elaborate religious images

- Jessie M King from the Glasgow School of Art

- Alasdair Gray and his emblematic designs for 'Lanark' (the original drawings for which are held in our Manuscripts Collections).

Our collections of Scottish children's books are particularly rich in illustrations.

Today, with the rise of computers and image processing technology, it is easy to produce books full of high-quality colour images. However, as our page on private press shows, the older techniques are still being maintained and developed in experimental ways. In 1981 the Library received a collection of the tools and woodblocks used by the Scottish wood engraver Agnes Miller Parker. Scottish writers such as Robert Louis Stevenson are continually attracting the attention of artists who want the opportunity to illustrate classic novels like 'Treasure Island'. (The Bartholomew Collection includes the engraved copper plate used to print the map in the first edition of 'Treasure Island').

Finding aids and consultation

It is not always straightforward to find out about illustrated books. Although newly created catalogue records should note the presence of illustrations (often abbreviated to ill. or to port. for 'portrait'), these are rarely described in detail, and many records for older books do not meet these standards.

Books with plates are often vulnerable and may be restricted to consultation in the Special Collections Reading Room.

We are increasingly trying to provide material with illustrative content through our Digital gallery. Early English Books Online (EEBO) and Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO), available in the Library, offer the option to search for illustrations in pre-1801 books. Please contact Rare Book Collections staff for more information.

Further reading

- There is a need for more research in this area. Our collections have many excellent examples of the different illustrative techniques and processes, as practised in Scotland and elsewhere, but there is currently no authoritative guide to Scottish book illustration, or to illustrated books in the National Library of Scotland.

- Bland, David. 'A history of book illustration: the illuminated manuscript and the printed book'. London: Faber, 1958 (shelfmark: H5.80.48)

- Horne, Alan. 'The dictionary of 20th century British book illustrators'. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors Club, 1994 (Issue Hall.Publ.7.3.3.H2)

- Houfe, Simon. 'The dictionary of 19th century British book illustrators and caricaturists'. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club, 1996 (Issue Hall.Publ.7.3.3.H)

- James, Philip. 'English book illustration 1800-1900'. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1947 (T.188.h)

- McLean, Ruari. 'Victorian book design & colour printing'. London: Faber & Faber, 1963 (SU.37 (shelved at C.6.2 McL))

- Muir, Percy. 'Victorian illustrated books'. London: Batsford, 1971 (H4.80.779)

- Schenck, David H. J. 'Directory of the lithographic printers of Scotland 1820-1870'. Edinburgh Bibliographical Society, 1999 (shelfmarks: GNE.1999.2.5, NRR)

Website

- British Museum's Department of Prints & Drawings

http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/pd/pdhome.html