'The Scotsman': From underground newspaper to Scottish institution

Introduction

Who founded 'The Scotsman'?

'The Scotsman' was founded by solicitor William Ritchie and his friend Charles Maclaren, a customs official. Frustrated at the lack of "spirited or liberal" opinions in the Edinburgh press, Maclaren considered setting up his own independent publication in the autumn of 1816. Around the same time, Ritchie had written an article about mismanagement at the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh and was struggling to find a publisher.

Ritchie suggested calling Maclaren's paper 'The Scotsman' and drew up a prospectus outlining its aims. Targeted at potential investors, this document explained that Ritchie and Maclaren wanted to "multiply the sources of rational amusement". The pair made no promise to deliver fine writing, but pledged to be impartial, firm and independent. This may not seem contentious today. However, in 1816 setting up an independent, liberal news outlet felt like a bold, almost revolutionary, move.

When did 'The Scotsman' first publish?

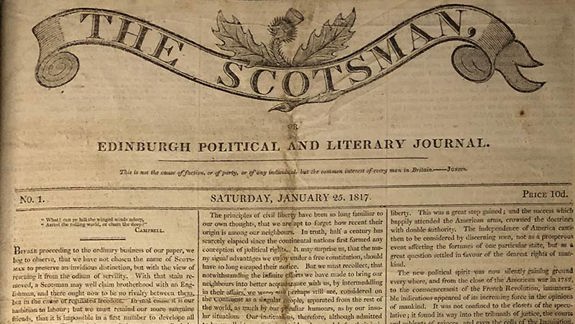

'The Scotsman' launched as a weekly newspaper on Saturday 25 January 1817. Fittingly, the paper came into the world on the birthday of another Scottish champion of free speech, Robert Burns.

Just eight pages long and about the size of a table napkin, the first issue cost ten pence. Since newspapers were heavily taxed at the time, four pence from each copy sold was handed straight over to the Government.

The masthead bore the subtitle, "Edinburgh political and literary journal" and an illustration of a thistle, a symbol of Scottish pride that still adorns the paper today. A brief statement on the front page asked readers to be patient – both those who expected more from the paper and those who felt it had gone too far. "In time," Ritchie and Maclaren wrote, "we hope to please both".

Maclaren himself wrote the leader for the launch issue. His piece exploring the development of civil liberty in Europe and America demonstrated the new paper's liberal outlook. Alongside news and discussion, the first issue featured an original poem and a report of an exhibition of pictures by the historical painter William Allan.

At the beginning, Ritchie and Maclaren expected few advertisers would be interested in a paper sharing such liberal opinions. The handful of advertisements that did appear included announcements of the second edition of 'Tales of My Landlord' by Jedediah Cleishbotham (a pseudonym for Walter Scott), a fifth volume of 'Lord Byron's Works' and a new part of the 'Encyclopaedia Britannica'.

Becoming a daily

As circulation grew from its initial 300 copies, an additional weekday edition was launched. But it wasn't until a major change in the law that 'The Scotsman' became a daily publication.

In 1855, stamp duty on newspapers was abolished. Freed from paying almost half its cover price to the government, 'The Scotsman' dropped its price to a penny and began publishing daily. As advertising duty was also removed, the paper's front page became packed with highly profitable classified advertising.

With the move to daily publication. circulation jumped to 6,000 copies. By the early 1860s, growth meant 'The Scotsman' had to move out of its premises on the High Street, regarded as the Fleet Street of Edinburgh.

Growth and technology

'The Scotsman's' new purpose-built, five-storey building stood at 30 Cockburn Street, where the paper's masthead was incorporated into the building's façade. From there, copies of the newspaper were sent to nearby Market Street, for distribution by road, and Waverley Station, for distribution by train. Carrier pigeons transported reports and score updates back to the office from race meetings, football games and cricket matches.

By 1865 circulation had risen to 17,000 and more growth was on the cards. Three years later, 'The Scotsman' became the first newspaper based outside London to set up an office in Fleet Street. Always embracing the latest technology, the newspaper linked the London team with the Edinburgh office by a wire service. The Cockburn Street office itself was connected to the Edinburgh General Post Office by a pneumatic tube carrying hundreds of telegrams every day.

In March 1872, a special express train began delivering issues to Glasgow. Papers were sorted on board, and bundles were thrown out at stations along the way. By 1898, an additional newspaper express ran to Hawick in the Scottish Borders. In just 80 years, 'The Scotsman' had gone from an eight-page weekly to one of the world’s outstanding daily newspapers.

Luxurious offices on Edinburgh's North Bridge

By the late 1890s, the need for new premises was once again pressing. When the North Bridge between Edinburgh's old and new towns was to be widened, the paper seized the opportunity to buy a prestigious new site. Meat markets, inns, oyster shops and coffee houses were cleared away and, in 1899, building on a new, wide thoroughfare began.

The North Bridge headquarters were designed by Scottish architects Dunn & Findlay. One of the architect partners (James Leslie Findlay) was the son of the then owner of 'The Scotsman', John Ritchie Findlay. He himself was the great nephew of co-founder William Ritchie.

The lavish yet functional North Bridge building cost £500,000. Adjusted for inflation, that would be around £55 million today. When the headquarters opened in 1904 it was a true marvel of the age. Probably the largest-ever private investment in the city at that time, and visible from much of Edinburgh, it stood as a grand statement of purpose and intent.

The upper floors were full of management offices adorned with marbled pillars, walnut panelling and chandeliers. Lower levels housed the most modern printing presses and a foundry where printing plates were cast. Everything was powered by electricity and linked by wire services to the wider world.

Though 'The Scotsman' office later moved multiple times, the North Bridge building still stands. It's now home to a four-star luxury hotel.

Championing the Scottish constitution

Championing free trade, parliamentary reform and Scottish devolution, 'The Scotsman' retained the liberal, independent outlook of founders Maclaren and Ritchie throughout the twentieth century.

One newsworthy event that prompted debate in the letters' pages of the paper was the theft of the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day, 1950. Also known as the 'Stone of Scone', the Stone of Destiny was used during crowning ceremonies of Scots monarchs for centuries. In 1296 it was captured by Edward I and taken to London.

"Scotland Yard are now trying to discover the destination of the Stone. Not unnaturally they suspect Scotland… It is not often that the people of this country are presented with so exciting a detective story on such a seasonable occasion."

Quote from 'Stone of Destiny', 'The Scotsman', 26 December 1950

As a symbol of Scottish monarchy, the stolen stone rekindled debate on Scotland's constitutional settlement, a debate in which 'The Scotsman' played a prominent role. In January 1992, to celebrate its 175th anniversary, the newspaper organised a high-profile debate on the subject. This event reflected the liberal spirit of 'The Scotsman' and endorsed its founding principle of publishing news and opinions "without fear or favour".

Featuring Scottish politicians and chaired by Scottish broadcaster Kirsty Wark, the debate raised awareness of issues surrounding devolution. Subjects discussed contributed to the devolution vote in 1997 and, ultimately, to the formation of the Scottish Parliament in 1999.

A unique window on Scotland's past

The National Library of Scotland holds every issue of 'The Scotsman' dating right back to that first edition in 1817. Looking through the newspaper's archive offers a unique window on Scotland's past. For instance, two reports more than a century apart highlight two moments in history when Scots were forced to leave their homes.

On 7 December 1822, the whole front page was given over to an article entitled 'Hints to emigrants'. Published in response to readers' requests for advice on where to emigrate to, 'The Scotsman' piece aimed to ensure people wouldn't be taken in by ill-considered schemes.

"The Guides to Emigrants hitherto published, we regret to say, are either miserable booksellers' catch-pennies, or delusive descriptions manufactured by quickish speculators to entrap the unwary."

Extract from 'Hints to Emigrants', 'The Scotsman', 7 December 1822

A follow up piece compared the advantages and disadvantages of moving to the United States or Canada. Weighing up the climate, size of cities and the quality and cost of plots, the article also warned of the dangers posed to livestock by wolves and bears.

One hundred and eight years later, an article published on 30 August 1930 painted a vivid picture of the last inhabitants of St Kilda as they left their island homes. The day before, islanders had been evacuated to the Scottish mainland at their own request, due to difficult economic circumstances.

"They have taken a last look upon the abodes which were their fathers' and their fathers' fathers', and cut themselves off from the existence to which time and tradition had accustomed them."

From 'St Kilda Evacuated' article, 'The Scotsman', 30 August 1930

A role on the world stage

Asserting its Scottish identity while proclaiming an international outlook gave 'The Scotsman' a presence on the world stage. An early example of this can be seen on 21 July 1969, when the paper reported American triumph and tragedy on its front page.

One front-page report covered the Apollo Moon landings, another the Chappaquiddick incident, in which US senator Ted Kennedy left the scene of a fatal car crash and didn't report the incident until the following day. 'The Scotsman' produced a commemorative copper plate of this cover in recognition of its importance.

Today, 'The Scotsman' continues to bring the world to Scotland and Scotland to the world. Its print edition and website still bare the thistle emblem and its current tag line reflects its original bold aims through the words "dare to be honest".

About the author

A member of our Published Collections team, Ian Scott is a Curator with a specialism in sport, leisure and newspapers.

Dive deeper

Newspapers

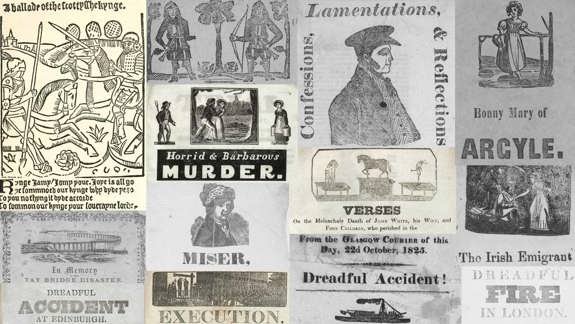

Scottish Broadsides: Three centuries of news and views

Printing and publishing